Filled with various fascinating

technologies and mechanical devices, Jungki Beak’s studio reminds one more of

an experiment lab rather than a studio. Upon closer inspection on the meaning

of the devices however, it’s evident that these mechanisms do not have much to

do with the so called conventional science, because although something is at

work, the operation of the devices not only contribute very little to the

discovery of (scientific) truth, it also does not rely solely on scientific

precision and validity. Merely applying such scientific experimentation and

processes into his oeuvre, Beak’s works are actually more like a type of

Para-technology which instigates new meanings never before unearthed by

existing scientific rationality. It’s a technology which, while parasitizing

existing conventional science, brings into question the (rationality of) system

of science through its altered signification and thus mutation. In the core of

all this seems to lie criticism on the Western rationality or science centrism,

and realization of their shortcomings, such as dichotomous division and

classification of body and mind, and human and nature. Beak questions such

binary oppositions and directs at their original integrated form before the

division. Beak’s work is based on his engagement with Eastern philosophical

world, in which all things in universe exchange and integrates with each other,

endlessly affecting each other in cycle of infinity. It also seems to follow

Buddhist teachings of the Principle of Causality in which all things in the

world function as a premise for something else, connected somehow and affecting

each other in complex and subtle ways. Paradoxically, however, the artist

applies the very western scientific methodology and technology in order to

demonstrate such Eastern philosophy. Beak’s work is more like a type of

pseudo-science, or spell or alchemy, in the sense that it appropriates

scientific methodology in order to criticize western scientific thought and its

limits. In addition, his work is ultimately an artistic experimentation or

performance in the sense that it focuses more on the connection or revelation

of a certain meaning rather than the strict operation of scientific principle.

This is why Beak’s work touches the human soul, which is an element that is

impossible to find in Western technological science, and thus Beak’s work is a

‘machine to touch the heart’. Like Foucault or Agamben’s argument, these

mechanisms fuel a sort of subjectivation, or function as a (an aesthetic)

technology which affects the microscopic emotional realm of life, or

internalized actions and thoughts of an individual.

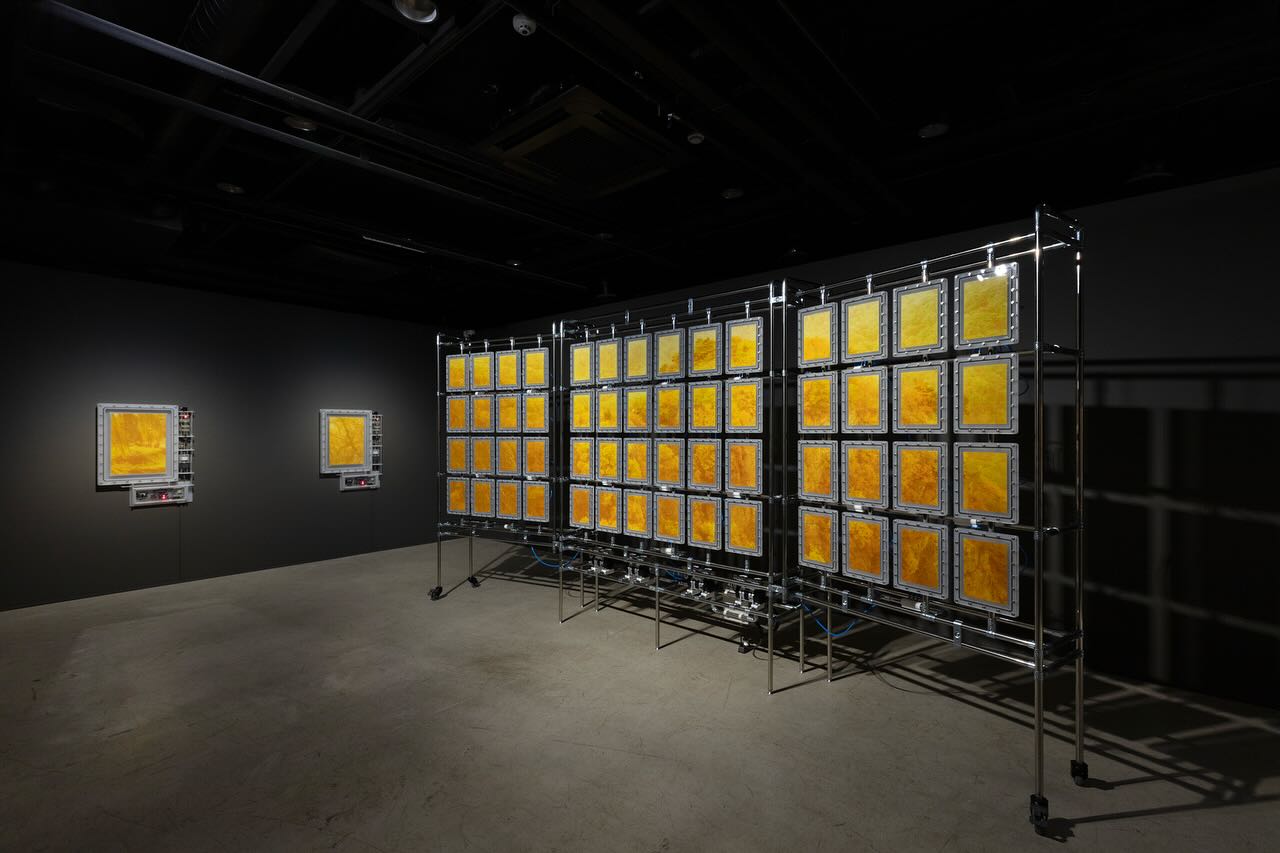

These aspects are best portrayed

in Beak’s work Pray for Rain, shown in his solo exhibition at DOOSAN Gallery.

In the work, the entire wall of the gallery is covered in clay and Vaseline

which is applied to the cracks and fissures that appear due to the evaporation

of moisture in the clay. Praying for rain is merely a gesture of wishing for

the rain, and is a type of black magic which practices the (incorrect) belief

that the human gestures and matters have supernatural power. While it’s nothing

more than a non/anti-scientific gesture, the symbolic aspirations and hopes for

the cracks of the earth to be filled up again signifies the desperation to heal

great nature. Human, even if he’s just a boundlessly powerless being when

facing nature, is filled with the desperation to at least pray for the rain

regardless of its non scientific effects when faced with a serious famine (he

needs to believe in something, even if it’s something groundless). And only

when such aspirations and desperations are accumulated can any changes take

place in this world. On top of these significations, Beak also wishes to fill

up the cracks in his (artistic) subject which implicatively suggests his

artistic practice. While these cracks signify actual physical ruptures in his

work, they also portray ruptures in earth and nature, as well as the

dichotomous rupture between body and mind, and human and nature. Allowing the

principles of great nature to circulate and permeate by connecting and sealing

together elements that are divided and classified, the fundamental gesture to

fill in the cracks and gaps is analogous to the function of water in nature.

This is evident in the fact that there are many works by Beak which focus on

the subject of water, including Pray for Rain: Mhamid (2008) in which Beak

himself becomes a shaman carrying out a performance of Korean traditional

prayer for rain, as well as the audience-participatory work Sweet Rain (2010)

in which Beak used saccharine to make sweet ‘rain’ fall in the exhibition

space. These works focus more on manifesting the particular meaning of water,

as a symbolic medium which allows circulation of matters on earth, rather than

the physical phenomenon of actual ‘rain’. Thus the artist places more

importance not on the physical operation itself of a certain phenomenon, but

more on the production and construction of meaning produced through its

physical operation. He ‘uses’ and ‘redirects’ technology as a mechanism to

generate meaning. Beak’s works not only generate meaning, but also question existing

meanings. In Blue Pond (2009), he alluded to the existing notion that ‘clean

pond is blue’, and produced an artificial pond using blue pigment, amplifying

the sense of distance between conventional perception and actuality. While such

experimentations on the activation and derivation of meaning expand and connect

to even more meanings, it seems that his works attempt to demonstrate the logic

of all things in the whole world through the interweaving of meanings.

While the use of Vaseline in this

exhibition can be in part explained by the linguistic meaning of Vaseline

—which fuses two disparate elements of water (wassor) and oil (oleon) — it also

relates to the artist’s personal experience of treating his burn and going

through physical suffering. It adds the meaning of healing to other meanings

mentioned above. The Vaseline, which the artist started using since his

Vaseline Armor series in 2007, demonstrates such meanings of healing. In the

series, Vaseline is shaped into gloves and armors to protect the individual,

and also becomes a healing element which fills up the cracks on buildings,

expanding the concept of healing from the level of an individual to that of the

society. In fact, the application of Vaseline, which is nothing more than skin

moisturizer, as a cure-all medication to heal all wounds, is probably driven by

a certain (non)scientific yet convincing belief, like ‘placebo effect’, or a

enchantment. Beak does not face away from such shamanistic aspects in his work,

as evidenced by the fact that the term ‘contagious magic’ is found in the

titles of the series Contagious Magic: Sprout, Forsythia, Azalea, Satuki and

Contagious Magic: 16 Reservoirs in this exhibition. They imply that because

everything in the world is connected and amalgamated, they still continue to

affect and connect to each other even after they’re separated due to certain

energy. These unique works –– in which the very material for the work itself is

extracted from the conceptual subject of the work –– are charged with

existential cause-and effect relationship in the sense that they capture the

(traces of) physical presence of the subject. It’s no wonder that such energy

is actually felt in the work, as they actually hold the subject’s presence (or

part of it). In Homeopathic Image: Japanese Apricot Flower, a new work

collaborated with Beak’s father, the flower (symbolizing fidelity and integrity

from a long time ago) drawn with electricity- conductive ink functions as an

antenna which transmits radio frequency and sends mysterious energy of the

flower everywhere. What’s important is not whether or not such energy and aura

is received, but the dimension of empathy, or the hope or conviction to spread

it to others. Homeopathic magic, which believes that similar things inspire

similar things, is partly a superstition and in itself has no scientific

validity and effectiveness. However, what’s more important is the sense of

desperation or the will to put it to good use, as can be seen in Pray for Rain.

What is meaningful is the aspiration, or the attempt itself to signify the

desperation for rain or water through the use of Vaseline, or to spread the

positive energy of flower through the antenna like flower painting. The same

desperation is also evident in the work Untitled: Egg Incubator and Candle

shown in this exhibition. Using the visible operation of mechanical device

which converts the heat of candlelight to electrical energy to hatch chicks out

of eggs, it captures the (bizarre) attempt to use the candlelight, which

symbolizes desperate aspiration, to give birth to chickens which drive away the

gloomy energy of the night and proclaim the arrival of morning. The science and

technology which the artist uses is just a de vice which touches the heart,

gives it form, and invites empathy from the viewers; and thus the significance

of his work rests in that it functions as a machine to touch the human heart.

Through such awkward but meaningful experiments and experiences which connect,

exchange and fuse the cracks and ruptures of conflicting worlds, the artist

practices his own intentional art of empathy that’s like science, shamanism and

spell, but is ultimately not any one of them.