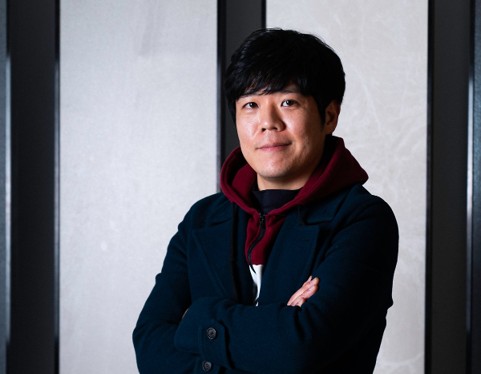

Jungki Beak’s solo exhibition

Contagious Magic also starts with water. When you pass through the entrance of

the museum, you will be met with the figure of a dragon, which is a deity of

water, holding up the exhibition hall. The dragon is called a ‘spiritual beast

of imagination’ because nobody has ever seen it, but most are familiar with it

through its depiction in the decorations of old architecture or costumes, or as

a tattoo on someone’s body. The dragon was partially a fictitious animal, and

partially an entity encountered in the everyday reality of the people of the

past. They turned to the animal when they sought to solve the problem of water

control mainly in two ways: the first was to offer heart-felt prayers to the

dragon to call or calm the rain and wind; the other was to drive the dragon to

move by teasing and provoking the dragon. This may seem absurd, but

occasionally the pray for rain is said to have really worked, and our ancestors

believed that it had some miraculous effect. It is quite a different system of

knowledge and belief from today’s. Jungki Beak summons the pray for rain to the

present and produces a numbers of Yongdu (龍頭, dragon head literally) made with a 3D printer and the scaffolding

for building construction to materialize a virtual Yongso (龍沼, pond where the dragon lives) in the exhibition hall. This is not

intended to follow the past or reinterpret the tradition in modern terms. It is

about transforming the exhibition space into a practical and magical place,

into a kind of symbolic space.

In fact, water contains a lot of

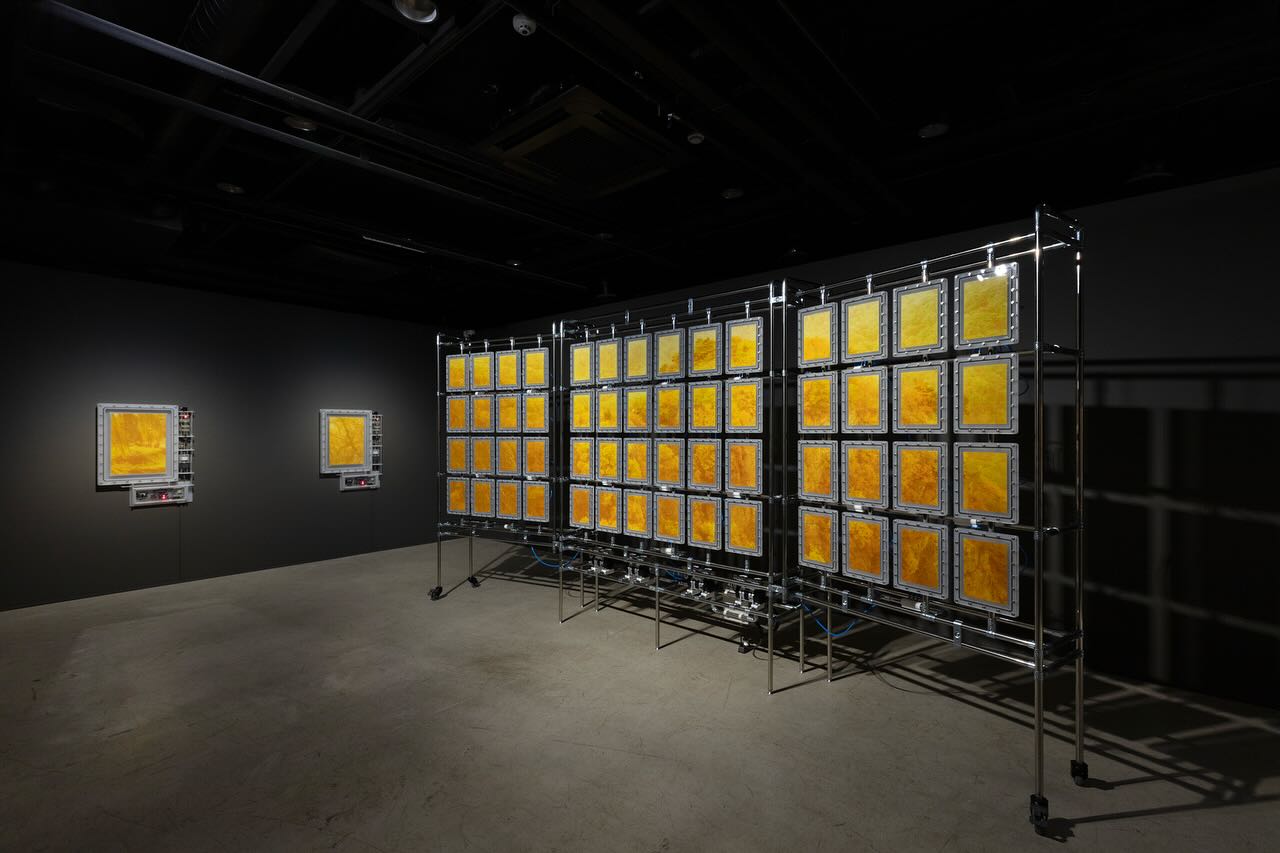

information that is invisible to the naked eye. His Is of series is an

experiment that converts the natural components contained in the water from a

specific site into pigments. Among the series, Is of: Seoul (2013-) is a print

of a typical scenery of Seoul. Beak made litmus paper from specimens extracted

from red cabbage, and used water from the Han River as ink for the paper. As is

well known, litmus is an indicator of acidity and alkalinity. The

acidity/alkalinity of a river that flows through a city contains information

about the various environmental factors it has undergone: from where did this

water flow in, how much rain has fallen, how severe the pollution is, what

pollutes the river, and how many people and industries are involved in the

region. Characteristics of water as a repository summarized in the phrase

“water memory” are actively accepted in homeopathy and used for treatment. Like

radioactivity that can be a cause of cancer under extended and intensive exposure,

but which can also be used for treatment under short and controlled exposures,

homeopathy is a therapeutic method of increasing the natural healing power of

the body by using a very small amount of the same substance as that which

causes the disease. The poison diluted in large quantities of water no longer

acts as a poison, but rather works as a medicine that aids the immune function

of the body. Jungki Beak’s Materia Medica: Cinis (2017) is an application of

homeopathy. By means of a video and installation, the work shows the process of

diluting and refining toxic substances into a drug. If you are an observant

viewer, you will find on the video screen the label “melted plastic” written on

the bag containing the raw material used for this work. This is a scene that

continues to raise the question, ‘Can people eat plastic?’, or, before that,

‘How and where did he get that stuff?’ In fact, this work is an attempt to

dissolve the black ashes which have been collected directly from a site of an

actual fire accident, and refine the components to make up a medicine. In this

process of ‘washing’ the poison with water, ‘poison’ does not just mean a

material residue. This is a psychological rite that dissolves the poison of the

bitter heart that of the pain, sorrow, fear, resentment, and remorse caused by

the fire.

Let’s go back to the question

raised at the beginning of this essay, ‘What happens to the dirt that is washed

away by water all throughout the world?’ It is still in the water. Yet, it

would have been diluted tens of thousands of times, diluting the idea of it

being ‘dirty’ and having changed from one place to another to have another

function and appearance. It would flow upon the surface of the earth, fill a

space somewhere, and eventually be absorbed into someone’s body. After all, we

all have a little bit of the same water. In a biological metaphor of the

Natural History Museum (2019), Jungki Beak plainly presents water, which is a

repository of memories, as a place of conversation and sharing of matter and

spirit. In this work he exhibits his reflections on a macroscopic level: ‘Well,

here are the samples of mammals on Earth, and as you can see on the labels,

they have different characteristics. But these organisms are both

diachronically synchronously connected to each other through the common denominator

that is water.’ Water is everywhere, in glass bottles of various sizes and

shapes, right in front of your eyes; even in the invisible convection currents

and in your very flesh and bones. After all, the memories of water do not

disappear, but is only stored somewhere.

Is of: Fall (2017) is the finale

of this exhibition that has presented a consistent perspective. This time he

extracted ink from the colorful autumnal leaves of the autumn mountain and used

it to print a photograph capturing that very mountain. The actual autumn

mountain scenery is processed to be transformed into a landscape in the photo,

but unfortunately the colors fade as time goes by. No matter how much the photo

is shielded from ultraviolet rays and immersed in acrylic resin to prevent

contact with oxygen, the change can only be delayed and not completely

prevented from discoloration. Yet the missing components of the colors are

probably left somewhere, somewhere in the vortex of the immense time and space

a human being cannot possibly perceive. There are so many things in the world

that we cannot explain, do we really ‘know’ what we think we know? Is it really

a coincidence that which we think is coincidence? In some big context, is not

all of this happening within the rules in which everything is already

programmed? Jungki Beak has been asking these fundamental questions all the

while in his search for answers. In the process, he uses architectural

structures, basic scientific theories, and empirical and concrete experiments.

Of course, people might be unfamiliar with the pipes, test tubes, long hoses,

and reagents placed in the exhibition hall, yet they can be understood as a

methodological strategy chosen by the artist in his search to find the answer.

Viewed in a larger context, what is the difference between science, magic, art,

and philosophy? Of the 4.6 billion years in the existence of the Earth’s,

humans have only existed 5 million years at the longest. In this period, the

life span of a person is roughly 80 years, accounting for a time period that is

as little as a speck of dust. To be sure, what we know is infinitely small.

Probably we are only under the spell of contagious magic because we were in

contact with all the things we happened to touch and pass by. Jungki Beak’s

work keeps our attention for a long time because it raises doubts over our

perception of what we have taken for granted and evokes our awareness of some

fundamental energy or force, and some inscrutable presence that are only dimly

perceived. Like water, composed of physical elements yet reaching the sphere of

the soul, like water flowing from one place to another, his work casts a spell

over us and passes from person to person. How about we immerse ourselves in the

reverie of his spell? It is my hope that this exhibition will be able to

‘enrapture’ us through the magic of the language and acts offered by Jungki

Beak.