I.

Idea Box

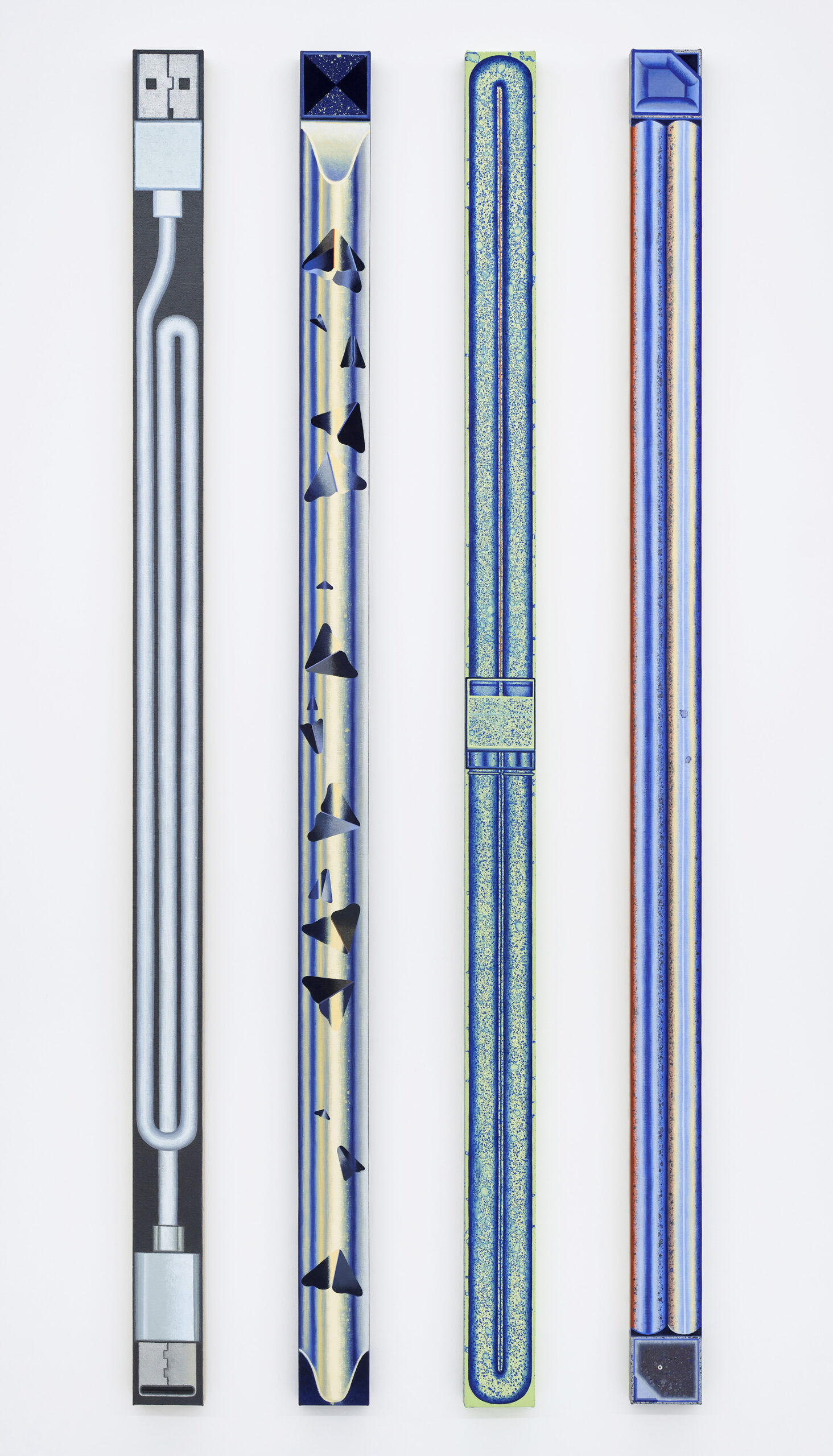

Drawing has long been a pillar of Park Junghae’s creative practice, not only as

a daily exercise for stimulating her imagination and exploring new ideas, but

also as an artistic medium unto itself. In many cases, her colorful works on

paper appear to be smaller executions of the same abstract shapes and

compositional rhetorics found in her paintings. Sometimes, however, she expands

this methodology to create sprawling arrangements of visual elements imbued

with a geometric sensibility. Grids of various scales serve as frameworks for

Park’s large-scale drawings, which are composed of multiple individual sheets

of paper lined up edge to edge that constitute a patchwork grid of their own.

Although the outlines of various forms are clearly delineated in these

expansive drawings, their interior volumes are left empty, resulting in

ghostlike silhouettes that expose lattices of ever-present gridlines beneath.

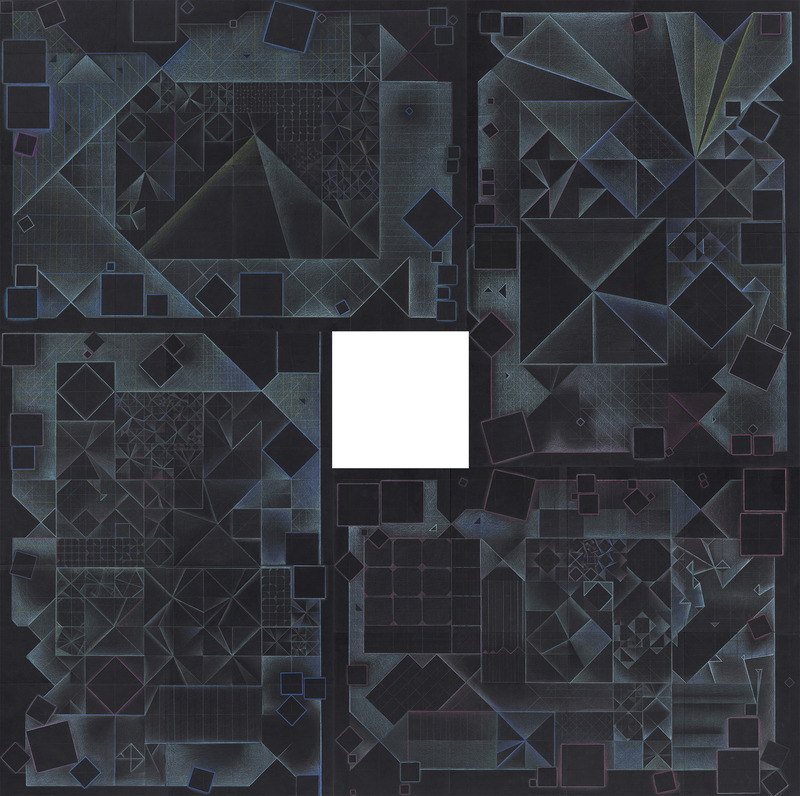

Park’s

recent drawing Zettelkasten (2024) amplifies this aesthetic

by inverting color values – images are rendered in white and pale pastels over

a matte black ground –to generate a photonegative effect. Areas of subtle

shading and muted gradients yield variable levels of translucence that elicit a

sense of flattened depth within the picture plane, reminiscent of an overhead

X-ray scan. The array of individual images that appear scattered within the

bounds of ‘Zettelkasten’ hints at the meaning of the drawing’s title: a German

term for a collection of notes, each containing a discrete bit of information,

written on cards and organized according to a cross-referential filing method.

As a personal knowledge management system, the concept of the Zettelkasten was

formalized by German social scientist Niklas Luhmann (1927-1998), who amassed

tens of thousands of individual notecards that formed a web of ideas he

referred to as his “secondary memory.”*

The

Zettelkasten method is non-linear, recursive and relational, allowing for

unexpected connections between previously recorded thoughts and newly acquired

knowledge. This is particularly useful for large repositories of information

such as Luhmann’s, but can also be applied to collections of loose-leaf

drawings preserved by artists like Park. While she may not organize her

sketches in a particularly systematic fashion, her archive serves the same

purpose within her practice; nothing is lost or forgotten and is always

available if the need arises to extract it from storage. It is in this spirit

that the “idea box” visualized in Park’s Zettelkasten

acquires significance as an indexical overview of the motifs and structures

that inform her most recent body of work.

II.

Emptiness Anxiety

The word “storage” implies the presence of something to be safeguarded, whether

it is kept in a physical space, on a digital server or inside one’s own brain.

By extension, anything not deposited within such a cache is put at risk of

being misplaced or erased. While this may seem undesirable from a conventional

standpoint, there are numerous instances when things are deliberately not

stored, especially if they are easily replaceable, outdated or hazardous. For

some people, the very notion of storage conjures thoughts of compulsive

hoarders who find it impossible to part with their belongings, regardless of

value or function. For Park, such thoughts give rise to alternative

interpretations of storage systems and psychologies of aggregation.

There

is a strange human impulse to fill the empty spaces we encounter – a

subconscious discomfort that arises whenever we are faced with the voids of

everyday life. Our desire to fill awkward silences in casual conversations or

to cram as many things as possible into a suitcase reflects the way that our

brains have been conditioned to release dopamine in a response to converting

emptiness into fullness. This is likely a byproduct of how we fundamentally

perceive empty space as an awareness of absence, or a potential location for

physical objects. The very idea of the void is thus predicated upon something

that is missing, reinforcing a cerebral dialectic that explains why empty

storage spaces compel us to put things inside.

An

artist’s sketchbook begs to be filled with future drawings, delivering a sense

of accomplishment when the last page has been used. This, in turn, stimulates

an urge to begin afresh with another sketchbook in an iterative cycle of

accumulation and renewal. In the digital age, a more familiar storage paradigm

is premised upon optimizing digital storage spaces for maximum efficiency,

whether it be the internal memory of a modern smartphone or the hard drive of a

computer. Any time we find ourselves running out of available space, we are

forced attempt to compress, consolidate or reduce the amount of data that we

choose to keep, transferring the rest to cloud storage solutions or physical

backups.

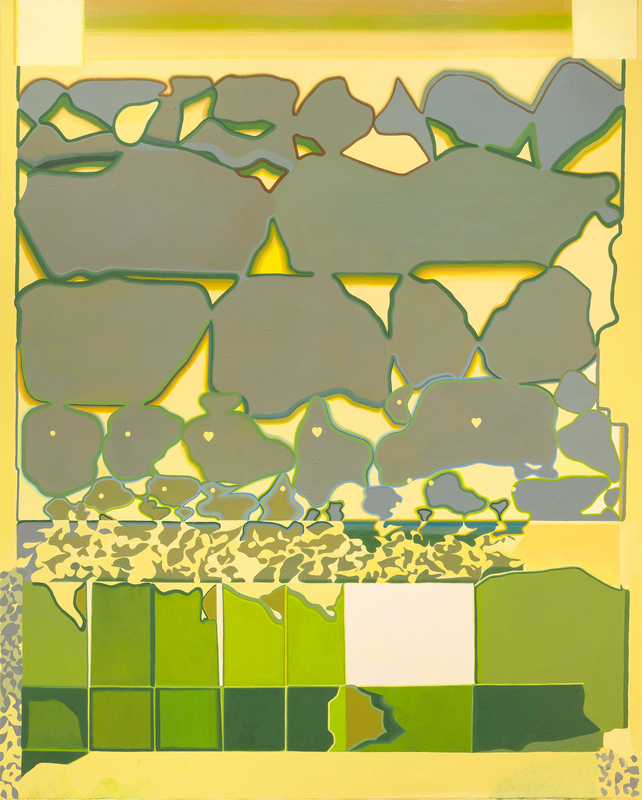

One

notable exception to these examples is the modern refrigerator, which is too

large an appliance for most households to augment with an additional unit. As

such, it is essential to periodically discard items in order to make space for

the endless intake of new foodstuffs. While some items such as condiments are

essentially non-perishable and can be kept for long intervals, other staples

such as produce, meat and dairy products are temporary occupants that must be

used within a limited amount of time or replaced with fresh items. As a hybrid

storage system, the refrigerator represents a specific yet ubiquitous case

study of collection management, as well as an idiosyncratic subject for visual

abstraction.