4.

Clearly,

Yezoi Hwang is absent from her photographs. This means that others appear in

her work as true “others.” The astonishing power of the self lies in finding

its mirror image in others; it always sees only what it wishes to see.

Conventional lyricism uses experiences and relationships with others in

everyday life as its primary material, but this ultimately amounts to a reunion

with oneself. Distance from the other is recognized only in order to be

integrated; difference exists to serve the expansion of the self.

Like the frog

or the beast that becomes human through love, the self absorbs the other,

making them part of “my” world. Understanding someone—whether of or through

them—is something already known. Love, too, is something already confessed and

loved. In Hwang’s photographs, however, the frog remains a frog, and the beast

remains a beast. In the photobook Season (2017), when she chooses

“gap” over understanding toward a mother who returned after ten years, reciting

that she is “making work that clarifies the distance between the two by tracing

the marks left on face and body,” the other remains eternally other, never

swallowed by the self.

Hwang

does not evade the “real” that frogs and beasts are ultimately frogs and

beasts. Her subjects appear not to be staged by the camera, but as if they have

crash-landed at the place where the camera stands—or rather, as if the camera

has crash-landed at the place of the subject. They appear free from the artist,

to the extent that even calling them models seems inadequate. In mixer

bowl_17(2016), the reason viewers cannot immerse themselves in the

contemplative figure is not because his concerns are trivial, but because he

exists as an other, like a piece of furniture sharing the same color scheme as

the box beside him.

This is not mere chromatic harmony; the body, built up in

the same yellow and reddish-brown as the boxes, insists on its existence as an

object that cannot bridge the gap except by being used—as a model. In mixer

bowl_48(2016), Season_18(2017), Season_21(2017), Season_24(2017),

and Maria(2019), figures are stacked, contained, or

affixed like surrounding patterns. Until darkness falls, camera and being exist

separately. Furniture does not speak.

That

the model becomes objectified stems from the firm physical and emotional

distance between “I” and the other. No situation opens a path to understanding.

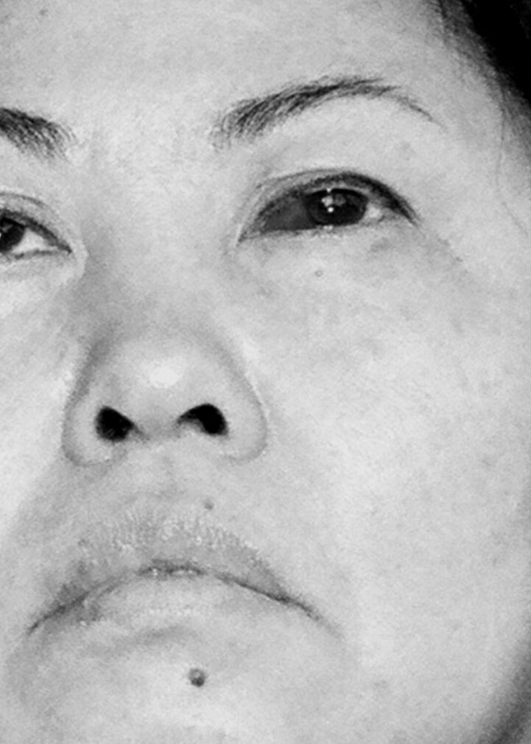

In the photobook “ill, evil, ghost”, figures are often shown in close-up

with expressions that resist interpretation, or only from behind with the

background erased, blocking contextual reading. In ill, evil,

ghost_29(2016), what is visible is not a narrative “truth” derived

from emotional identification, but merely the fact that a person stands with

their back turned. In ill, evil, ghost_19(2016)

and ill, evil, ghost_20(2016), the mother appears

repeatedly in the same place, provoking narrative linkage, yet the self cannot

pry open her closed mouth. The images verge on abstraction: darkened eyes

become circles rather than pain, wrinkles become lines rather than time. Where

the tyranny of the self is prohibited, the other’s alterity erupts. Like the

mother who appears unbidden, the other arrives suddenly, contrary to intention,

and the shutter is released in surprise.