More

than a decade ago, something happened during my time in the military. A

corporal who had had his leave cancelled was clicking away at a computer in the

on-base PC café. Curious, I looked to see what he was doing—he was navigating

to his home using Daum Road View. His response was astonishing. “Doing this

makes me feel like I’ve gone home.” While I could (internally mocking him)

understand the idea of enjoying a virtual vacation, I also felt a strange

unease. The scene he was looking at belonged to the past—at least several

months old, perhaps even years. What, exactly, was he seeing?

With

the advent of the so-called metaverse era, the virtual and the real have begun

to overlap. Yet this overlap is not synchronized solely in real time. Realities

from years ago migrate into virtual space, forming overwhelming simulacra, and

these virtual images become chaotically entangled with the present. The overlap

of the virtual and the real inevitably produces an overlap between past and

present as well. A technology in which datafied pasts are eternally mixed with

the present—this is the true nature of the metaverse that no one talks about.

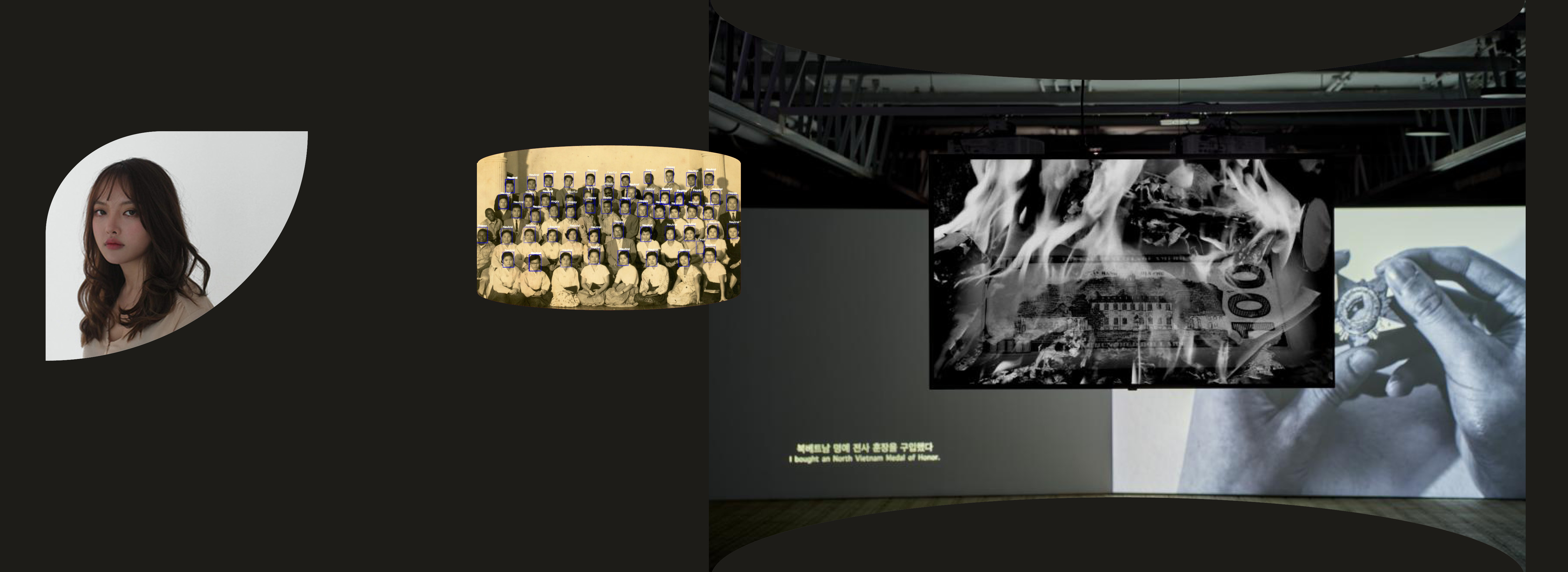

Yeoreum

Jeong’s short films and visual art works Graeae: A Stationed Idea (2020)

and The Long Hole (2021) unravel stories of

unidentified spaces and figures encountered within this process of overlap. The

first work, Graeae, begins from a first-person

perspective in which the narrator and the artist coincide. The three sisters

Dino, Enyo, and Pemphredo are known as the Graeae, beings who share a single

eye. Taking turns, they hold three different visions within that one eye. Among

them, Enyo—the goddess of war—secretly takes the eye away from her sisters, and

the narrator declares that she will tell Enyo’s story. Although the narrative

centers on the war-mongering Enyo, the perspectives of the other two sisters

overlap throughout the work.

The

artist plays the augmented-reality game Pokémon GO. Pokémon GO is a game that

overlays game space onto real space using GPS data, allowing players to

encounter, battle, and capture monsters at specific points while walking

through the city. Spaces where players duel one another are called “gyms.”

These gyms are typically designated at sites with historical significance or

places where people gather, such as churches, and are often selected through

players’ requests.

As

the narrator heads toward a nearby gym, she stops in front of a U.S. military

base. Within the game, this area is clearly marked by more than ten gyms, yet

in reality it is a place that one cannot easily enter without prior

authorization. It is here that the artist’s investigation begins. Why does this

area exist, and who were the people who once lived inside it? By hacking

Pokémon GO’s GPS system, the narrator virtually infiltrates the U.S. military

base. She then traces images and fragments of information scattered across the

internet, gradually assembling a single story. This is a distinctive aspect of

Yeoreum Jeong’s practice: by relying solely on fragments of the past dispersed

throughout networks, she deliberately creates gaps and fills them with fiction.

In doing so, she speculatively overcomes the limitations inherent in

collage-based found-footage filmmaking.

The

narrator discovers that the former Yongsan U.S. military base site had been

closed to civilians for an astonishing 114 years—from the period when the

Japanese military began full-scale occupation following the Russo-Japanese War

in 1904, through the subsequent U.S. military presence. On Google Maps, the

site appears merely as a patch of green—an enigmatic space that exists but

cannot be accessed. Beyond this, the narrator traces the lives of U.S. soldiers

inside the base. Homesickness is classified as a military disorder, and to

prevent it, the interiors and architectural designs of the base are

meticulously Americanized. Cafeterias are installed more vividly than in the

mainland United States, and the buildings along the streets are kept low.

Within the base, soldiers reenact the glorious American life of their childhood

memories.

Between

a Pokémon captured in front of a military base, land that remained inaccessible

for 114 years, and U.S. soldiers living on Hollywood-like sets, which

experience is more virtual? Yeoreum Jeong inverts Jean Baudrillard’s

proposition that “Disneyland exists to conceal the fact that the real country,

all of real America, is Disneyland.” Instead, she suggests: “Pokémon GO exists

to reveal the real colony—Korea—and to expose the idea of the U.S. military.”

Here, the artist’s strategy of weaponizing game algorithms stands out. Equipped

with an augmented-reality gaze and internet-based archival exploration, history

begins to appear with greater clarity.

In this sense, virtual reality is not a

system that produces something fictitious; rather, it is a technology that

summons what had been latent in reality—things that certainly existed but had

remained unseen due to deliberate forgetting. For Yeoreum Jeong, the virtual is

not a copy or imitation, but another name for the potential. She is a medium

who summons these potential ghosts. Rather than a clear division between

virtual and real, the condition for ghostly emergence lies in the way data from

past realities becomes virtualized on one hand, and overlaps with the here and

now on the other.

“Records

disappear in reality, but remain in the virtual world.”

—from Graeae: A Stationed Idea (2020)

The

film initially resembles a documentary depicting a gamer’s historical

investigation, but gradually shifts into a mystery genre that traces the ideas

and conspiracies of the U.S. military as a war machine. The film’s dreamlike

and eerie background music functions as a device facilitating this shift in

mode. At the same time, the work takes on the quality of a philosophical essay,

as it reflects on and doubts the artist’s own vision and visual experience.

Wandering through online and offline spaces like a flâneur, extracting the

sublime from kitsch, Yeoreum Jeong’s working method evokes the imagination

that, had Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project reached 21st-century

Korea, it might have taken precisely this form.