Seo

Minwoo’s practice begins from an understanding of sound not as a simple

auditory stimulus, but as a material event that occurs between space, the body,

and objects. He focuses on the vibrations, traces, and collisions that sound

leaves as it passes through various media, examining listening as a process

that unfolds continuously across time and space rather than being confined to a

single moment. This perspective is clearly articulated in his first solo

exhibition 《EarTrain_Reverse》(RASA, Seoul, 2021), which foregrounds a perceptual shift in how

space is sensed and imagined through sound.

In the

early ‘EarTrain’ works, Seo combines experiences of movement and listening to

explore how sound constructs space. Works such as Eartrain 50-00,

50-08, 08-00(2021) emphasize sounds collected from specific locations

to form an “auditory landscape,” while pieces like Traveler

E&C(2021) attend to everyday noise and subtle sonic textures,

focusing on sound as an event rather than as a carrier of narrative or emotion.

During this period, sound functions as an index that reveals concrete situations

and conditions.

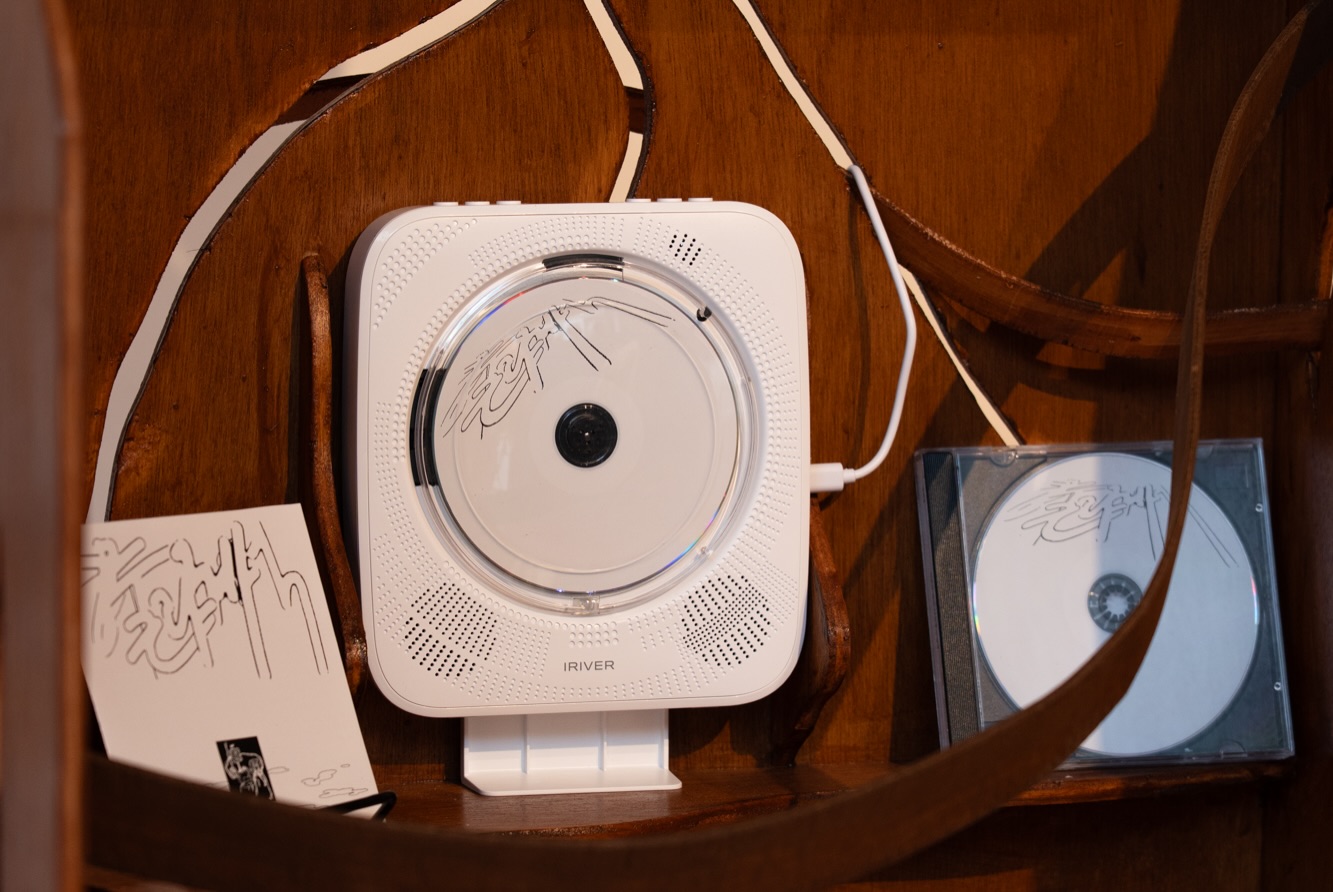

In the

solo exhibition 《earcabinet》(Mullae Art Space, Seoul, 2022), the artist questions the very

notion of “perfect listening,” bringing forward the fact that sound is always

accompanied by loss and distortion. Listening here shifts away from clarity and

faithful transmission toward an experience shaped by absence and

incompleteness. Sound is presented not as something that can be fully grasped,

but as a phenomenon that resists total apprehension, prompting a

reconfiguration of the conditions under which listening occurs.

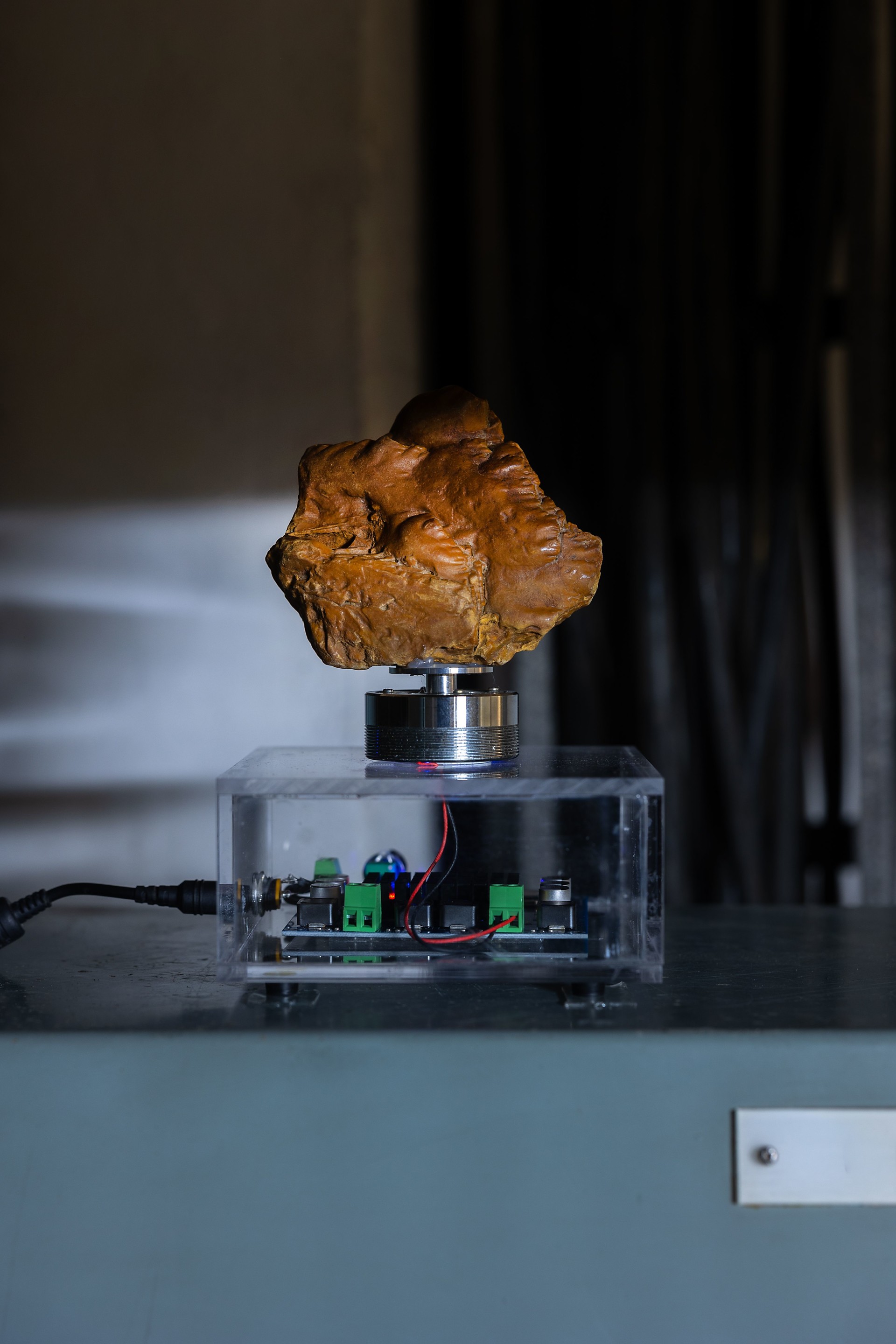

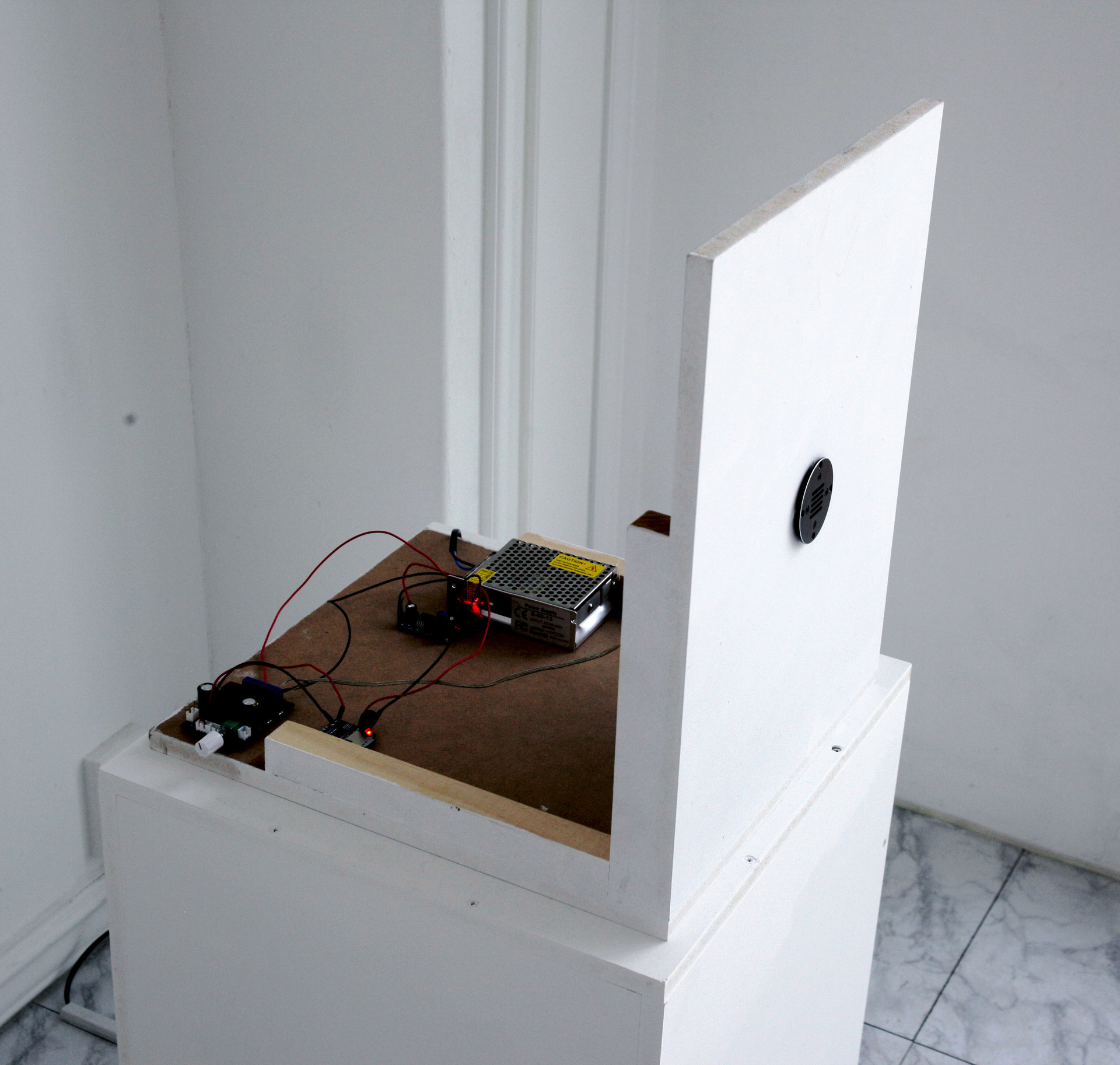

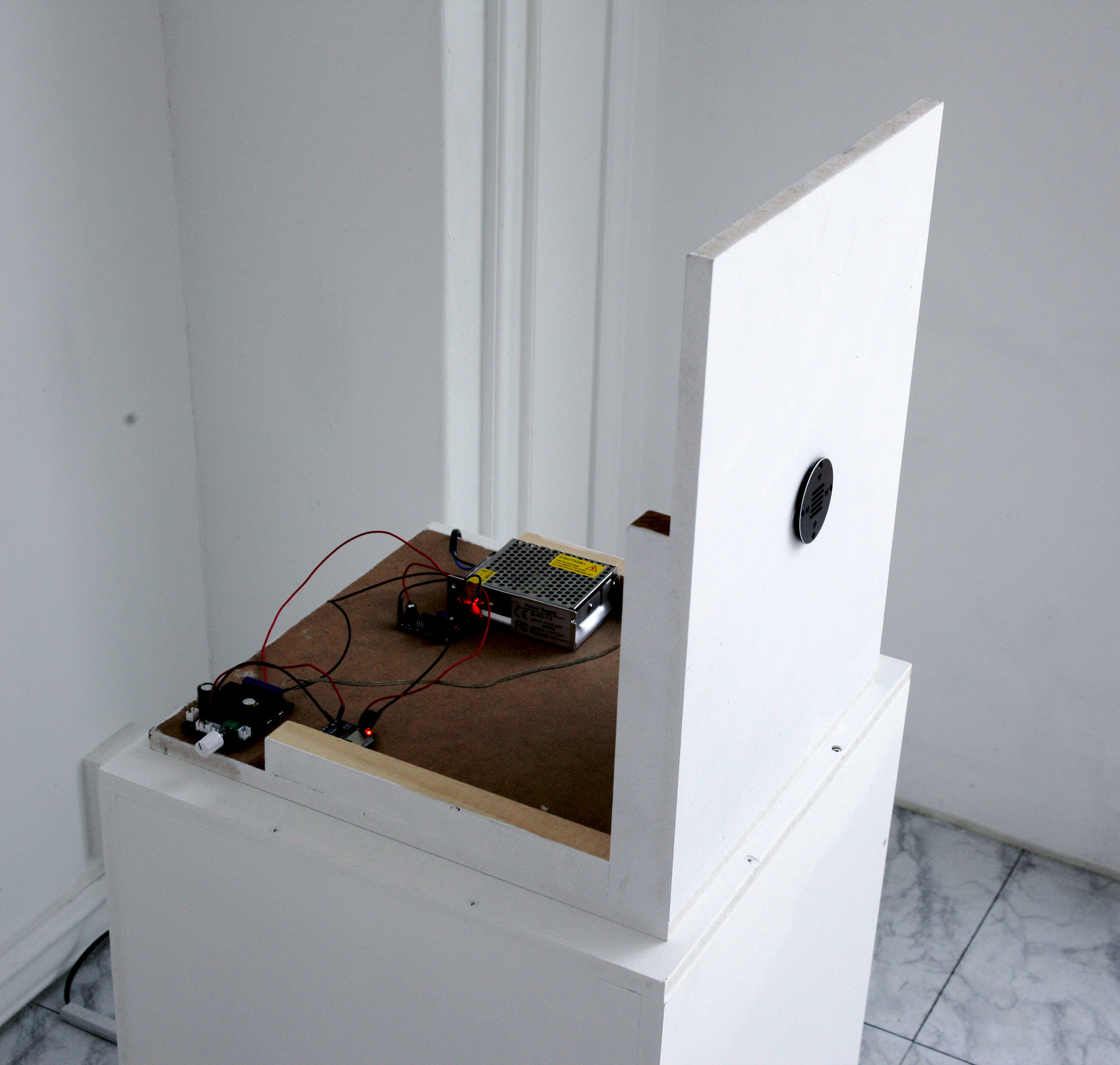

In more

recent works culminating in the exhibition 《Slough and Trajectory》(Arcade Seoul, Seoul,

2025), Seo expands his inquiry toward the residues and traces that remain after

sound has passed. The structure connecting the album Slough and

Trajectory: Spiral Horizontally World(2025), the performance Slough

and Trajectory: Trajectories(2025), and the exhibition itself

clarifies his approach to sound not as a finished output, but as an event that

emerges, disappears, and leaves behind material traces. In this process,

listening extends beyond the ear to become a temporal and spatial trajectory

experienced through the entire body.