I

spent a long time considering from whose position I should view these

photographs. I chose to view them from the perspective of the artist’s

mother—the position most familiar to me. The perspective of someone who either

took the photograph or was photographed, who has never handled professional

cameras, but has only taken pictures with disposable film cameras or widely

accessible digital devices such as smartphones. This is perhaps the only way I

can freely approach my relationship to photography.

From

this experience, I attempt a degree of conceptualization and theorization. I

would call this “photography without records.” These photographs do not arise

as outcomes, but emerge from the photographer’s consciousness, reflecting upon

the act of photographing itself. Let us examine the latter first.

Photography

is activated within various classificatory systems depending on purpose and

method: identity (amateur, professional, technician), subject (portrait,

landscape, object), genre (journalistic, artistic, commercial), and so on.

Perhaps it is more accurate to say that classification systems arise according

to each purpose and method. Among these, photography as a professional art form

uniquely records, reflects upon, teaches, and bequeaths the act of

photographing itself. This feedback loop—where photography influences

photography—allowed the medium to be recognized as a modern art genre.

Conversely,

consider photographs whose actions are defined by purposes other than

photography: leaving evidence (in court), commemorating events (weddings),

representing oneself culturally (selfies). These practices become subjects of

sociology or anthropology, not photographic discourse. Photography ends there

as something other than photography. The reverse—non-photography becoming

photography—is rarely observed, simply because we lack the institutional

motivation to observe it. But what if the reverse is already happening? What

would occur if we chose to observe it?

Long

before photography as we know it emerged in 1839, “cameras without film”

developed in various forms. The camera lucida, for example, used a prism lens

to overlay the image of an object onto a drawing surface, primarily for

painting. One might even describe it as a “hand-exposed photograph.”

Sensitization—literally sensing light—did not rely on chemicals, but on manual

skill.

Even photographic printing itself began as an attempt to eliminate

drawing—what might be called “photography without drawing.” Contemporary

artistic photography continues this trajectory with practices of “photography

without shooting.” Photography’s concepts and practices have continually been

redefined by altering their conditions and functions, whether intentionally or

forcibly.

What,

then, of “photography without records”? I consider this not through recent

academic theory, but through the images filling my smartphone album. Just as

memory is triggered by particular forms of recording, records derive meaning

only when remembered. I think of artists who have published books curated from

hundreds of thousands of smartphone images. Yet I know I will never revisit

most of my photos. If they were deleted, I would feel little more than vague

regret. The reaction after Cyworld’s collapse was similar—people had forgotten

not only the images themselves, but even the fact that such images once

existed.

These

photographs existed only in the moment of capture. They resemble underlining

passages in a book one never plans to reread. The underline is not useless—it

extends the moment as a moment. Naive realists who tell people busy

photographing meals, performances, or landscapes to “just look” misunderstand

what is happening. Photographing is an act of arranging visibility and

exposure, sometimes of waiting for events to persist, and ultimately of seeing.

Perhaps we saw for the first time through that small screen.

What

do we choose when we photograph? This question recalls ancient debates on

memory. The fear that reliance on written records erodes the will to remember

dates back to antiquity. The digitization and automation of record-keeping

render such fears more legitimate. Data preservation and memory may thus be

fundamentally different matters. Perhaps “photography without records”

completes itself not through preservation, but through disappearance.

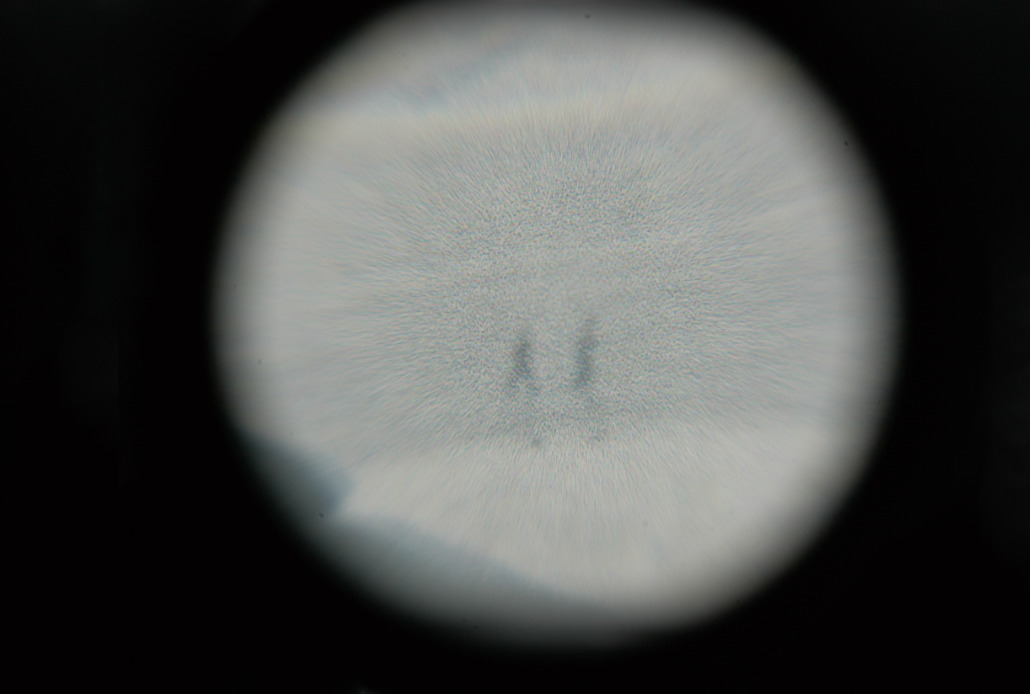

From

this point, I leap from experience into theoretical imagination. How does art

photography respond to “photography without records” emerging in mass

photography? Sangha Khym prints photographs on thermal paper; dots spread,

colors collapse into black and white. She adjusts the degree of degradation,

sometimes rubbing the image by hand. Images that once pointed to specific

individuals and memories are released from private ownership. Any everyday

photograph produces the same visual outcome, making the form itself more

significant than the content. This work operates as a device.

But

is replacing individuality with another form not simply another automated

system—similar to criticisms often leveled at non-art photography? Can we take

pleasure in such transformations? The anonymous hand rubbing the image, the

mythic threat of intervention from outside the image, becomes more explicit. We

never demanded the return of memory or record. Faced with this intervention,

what do we see?

As

gestures of transformation approach threat, unexpected images emerge. As

photographs are cut, heated, and copied, as erasure approaches physical

deletion, the image transforms and begins to recover its specificity. Nearing

nothingness—but never reaching it—the internal elements of the image call to

one another. The image even calls forth the mother’s photograph: the polka-dot

dress overlaps with digitally degraded halftone dots. We may now call the

mother’s eyes large dots. That abstract patterns can be read as acts of calling

is almost magical.

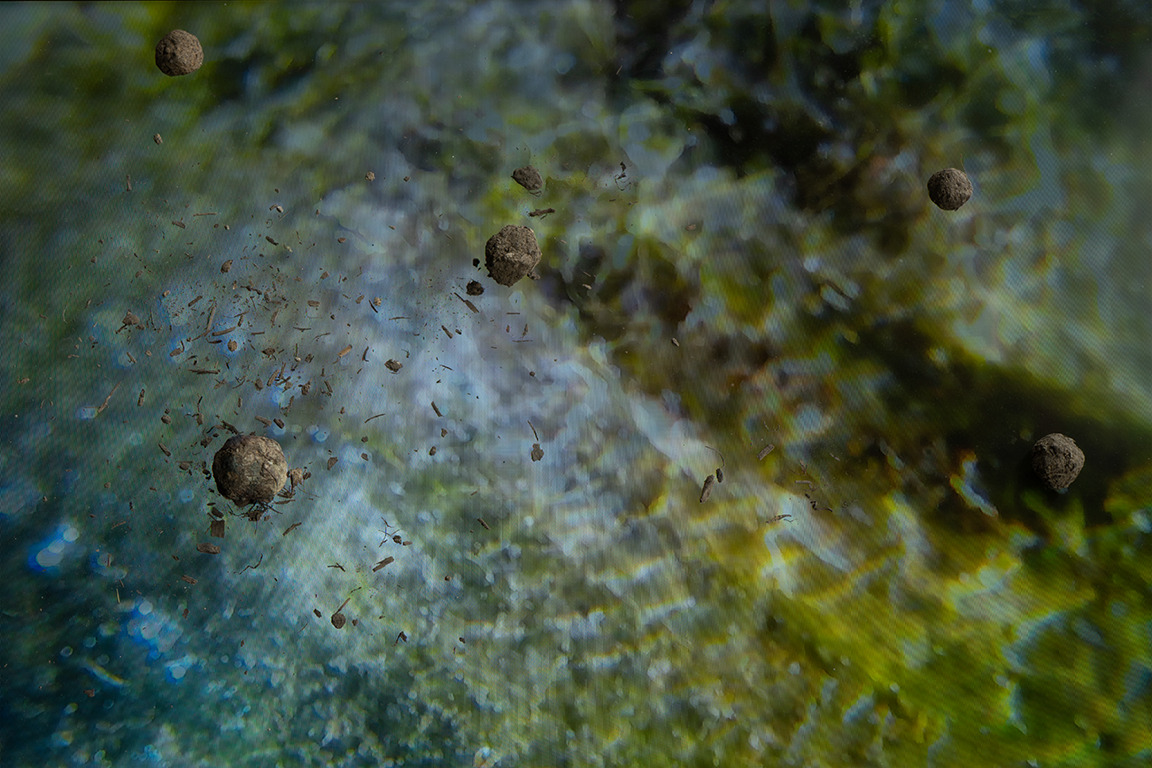

Bae

Ja-eun projects such calling into the future, where the absence of an addressee

demands a new body. She describes photographing objects that melt, lose form

and function, or merge into a single body—spaces that resemble her thinking.

When accidents circulate through me and are reproduced by my actions, spaces

“resembling” them reproduce accidents and circulate as photographs. We move

from reality’s logic to photography’s own operational logic.

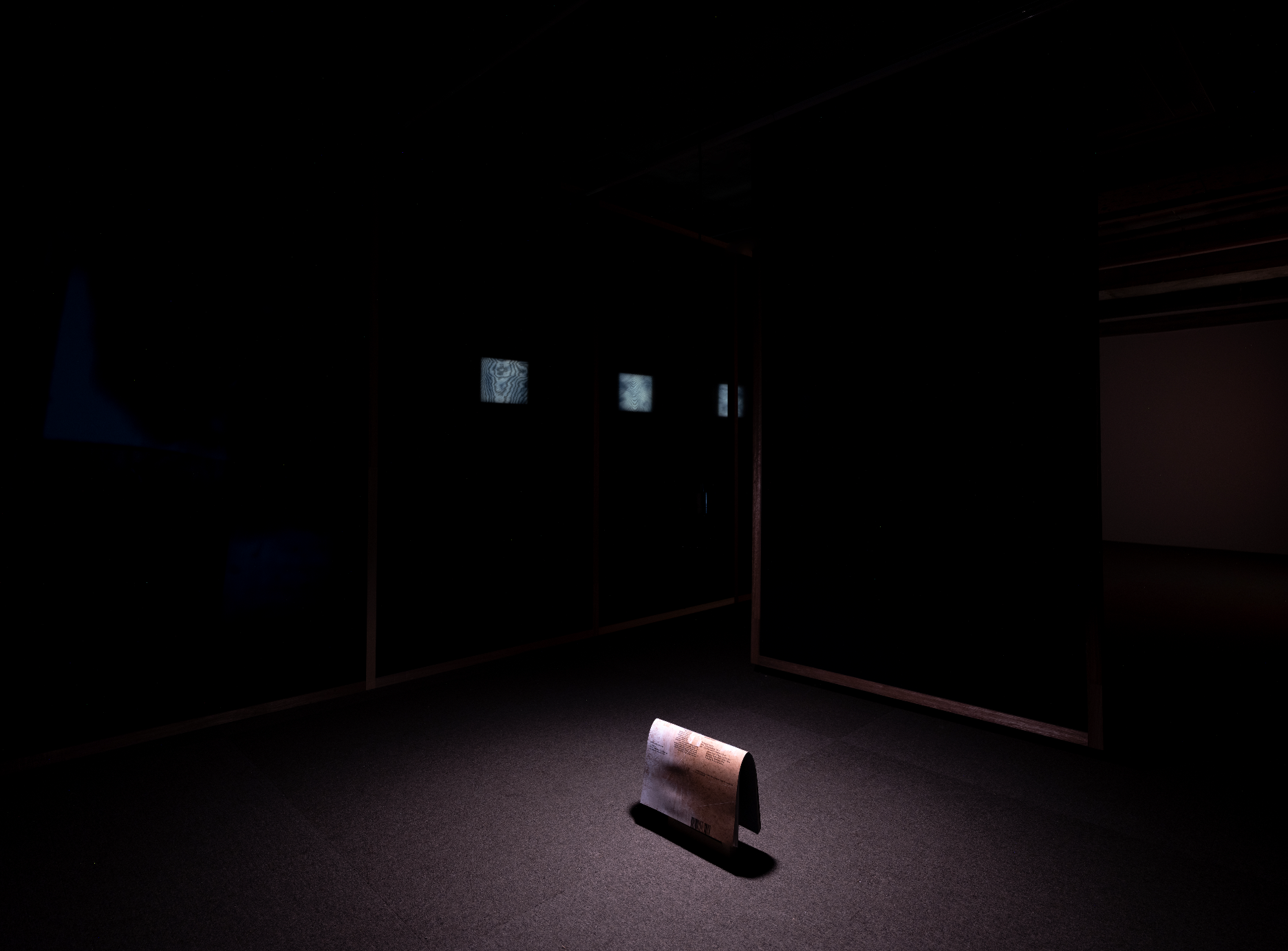

Yet

Bae Ja-eun interrupts the passage from circulation to appreciation. She burns,

melts, and attaches images. The transformed image does not demand

interpretation of its result, but of the act of transformation itself. The

image loses its reason to remain flat, migrating onto videotape and textile

surfaces. The original event becomes a state of things.

The

desire to make “my mother’s memory my own” became a key for interpreting Khym’s

images. Bae Ja-eun describes her own work as repeatedly excavating memories

left in the form of trauma. How should we read such a statement, which seems to

depict self-harm? Trauma cannot be directly extracted; the image must first be

burned. Burning here does not function as deletion—it lends the image the body

of something else. Within an approach that must simultaneously hold the

opposing goals of erasure and remembrance, photographs lend their bodies to

memories we cannot see, but must somehow confront.

Even

this borrowed body is destined to disappear. Earlier, I claimed that

“photography without records” had emerged in mass photography. Rather than

observing it, I asked what would happen if we allowed ourselves to be observed

by it. When hierarchies between domains are replaced by relations of influence,

this is the response sent back by professional photography.