Looking

at photographs of one’s mother when she was young inevitably feels unfamiliar.

Most people have experienced this at least once—flipping through an old album

and encountering a mother who looks different from the one they know: younger,

beautiful, carrying dreams and futures unknown to the viewer. Combined with a

past landscape that differs from the present, the sense of unfamiliarity

deepens.

However,

looking at old photographs of one’s mother is not the same experience as

viewing her Cyworld page. Whether they are travel snapshots or group photos

with friends, album photographs function faithfully as records of moments.

Photos uploaded to social media, however, carry an added layer of meaning. A

selfie—or even a non-selfie that one deliberately chooses to share—cannot carry

the same meaning as an album photo. If photographs of the past were tools for

recording memories, digital photos uploaded online are means of

self-expression. They represent a version of oneself shown to others, an image

shaped by how one wishes to be seen.

Because

these images reveal how a mother perceived herself and how she wanted to be

seen, encountering them provokes an even stranger feeling. Most daughters are

unaccustomed to seeing their mothers express or present themselves publicly.

Since daughters encounter their mothers primarily in private spaces, they

rarely experience how their mothers represent themselves socially. Moreover,

the mother from before the daughter’s birth—or from the daughter’s early

childhood—is someone the daughter never fully knew. To see her is to encounter

what feels like an entirely different person.

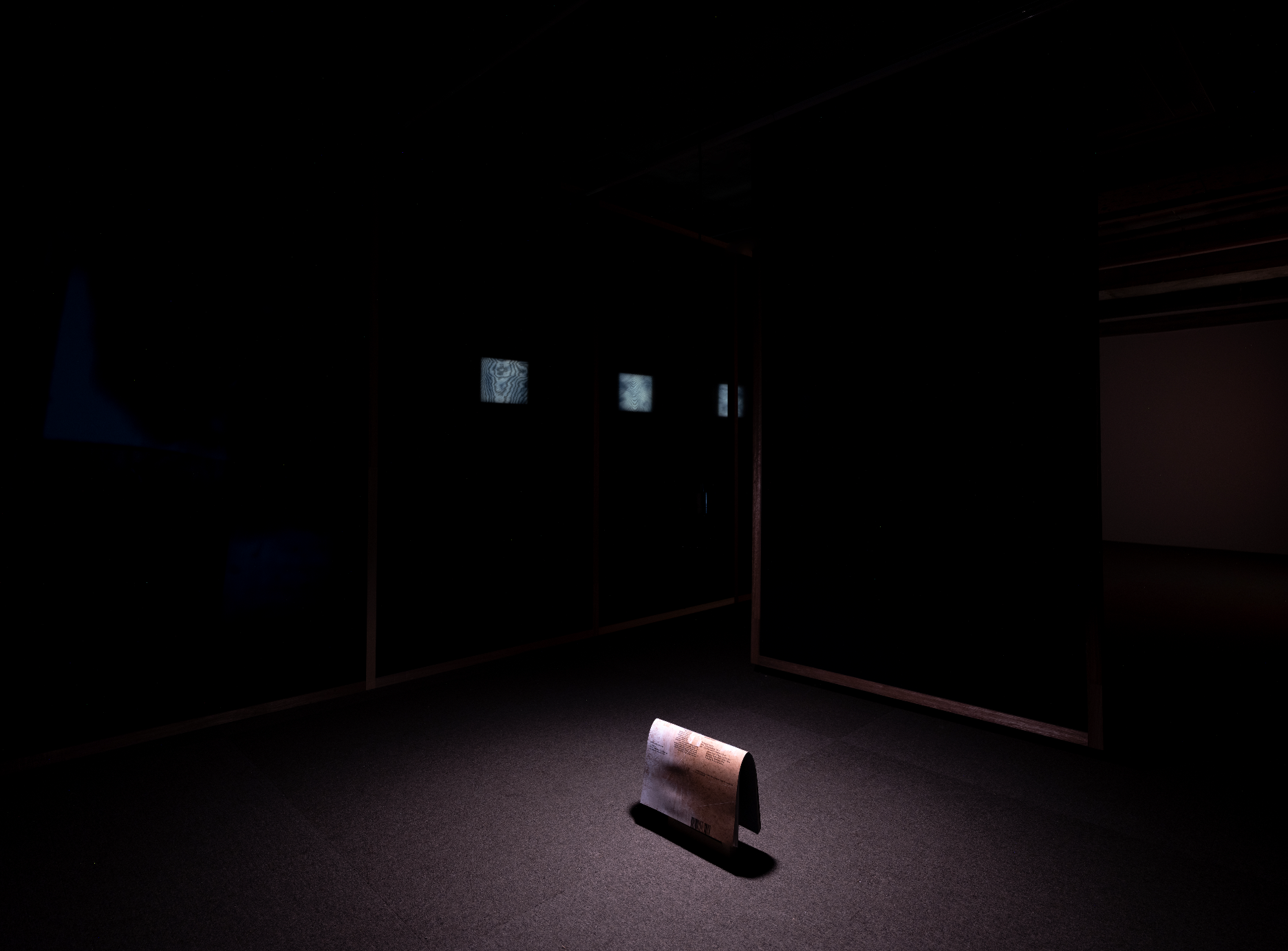

Sangha

Khym describes feeling this same sensation when she first encountered her

mother’s photos on Cyworld—a feeling that these images could never truly become

her own memories, that she would never fully know the mother in those

photographs. Rather than allowing the images to remain as online data destined

to be lost, Khym chooses to print them, turning them into material objects. Yet

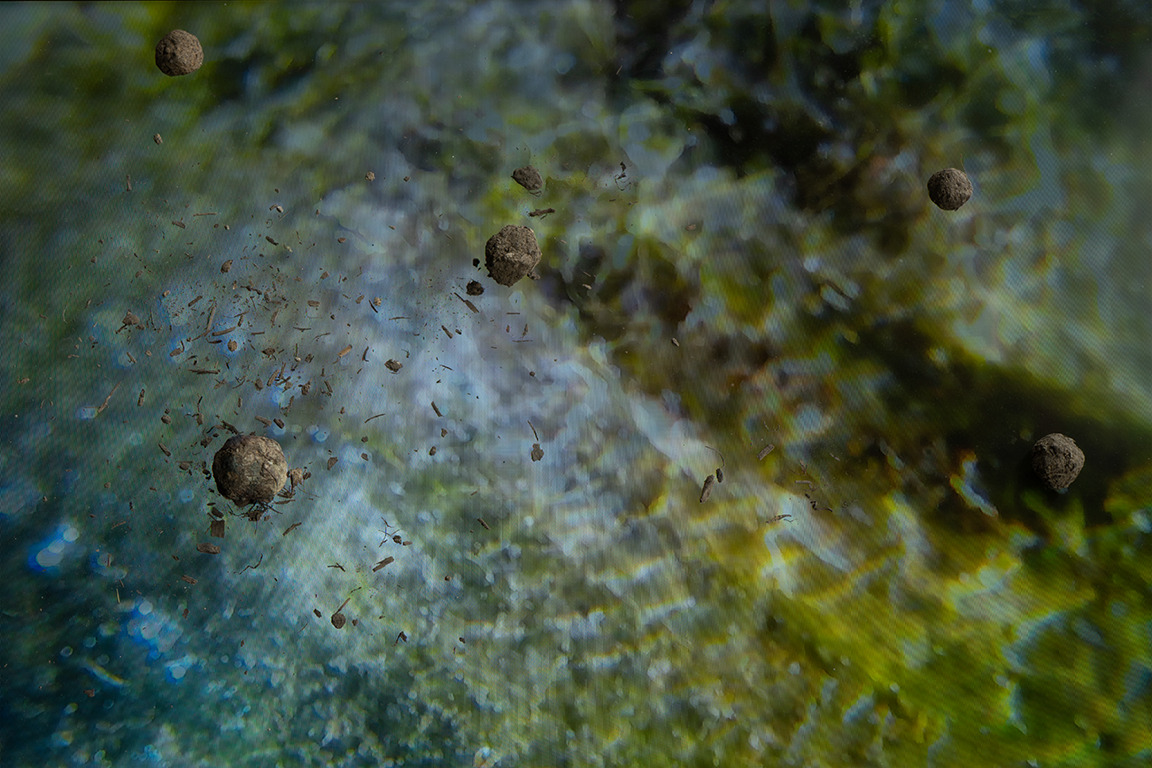

the material she selects is not one that lasts. She prints the photographs on

thermal paper—receipt paper printed by heat without ink. Vulnerable to heat,

thermal prints fade over time. Khym then exposes these printed images to heat

once more, transforming them. By blowing on them or rubbing them with her

hands, the images gradually lose their form.

It

is as if she attempts to understand—or somehow reach—her mother’s image by

erasing her face with the heat of her own body. Yet, as evident as her labored

breathing, it is equally evident that she can never reach her. Mother and

daughter are destined to misunderstand one another.

Photography

is a means of recording and remembering subjects. In photographs left to

remember a subject, Khym paradoxically discovers the impossibility of fully

knowing that subject. This realization is especially acute when the subject is

one’s mother—someone who feels closest, yet remains profoundly unknown.

Through

carefully observing, materializing, and transforming her mother’s photographs,

Khym may have come closer to her in some sense. Yet she can never fully know or

understand the mother in the image. A moment of time recorded remains

incomplete, and this incompleteness is the fate of photography itself. It is

always insufficient—forever unreachable, never fully remembered, and inevitably

misunderstood. In this way, it mirrors the unresolved relationship between

mother and daughter.