The

conversation between two people begins as a book is opened. “Is this your

grandfather?” A hand turning the pages stops and points to a photograph. “Yes.”

The questions continue. “Where was it taken? When was it taken?” Sangha Khym’s

video work gather(2024) begins this way. Questions

about a subject, place, and time recorded in or through a photograph emerge

only when the image appears as a clear figure. Otherwise, most questions

inevitably remain abstract—What is this? What was photographed? As I watched a

scene that begins with such concrete questions, a memory surfaced: a summer day

when I took a Han River cruise.

Once

aboard, it seemed that people were not particularly interested in the scenery.

Since the boat did not head out to sea, the ride was short, and there was

little that could truly be called a spectacle—perhaps this was only natural. I

looked at the scenery while exchanging conversation with Sangha Khym, who had

invited me. “That’s the National Assembly building, right?” “Is this Yanghwa

Bridge? Oh, it’s Mapo Bridge.” “That must be Bamseom.” Bamseom—at the time, I

did not yet know that this island would later become the central subject of

Khym’s solo exhibition. The experience of talking about visible objects, and my

memory of that experience, recalled the opening of gather(2024).

Khym’s

memory of Bamseom is as follows: “When I was young, there was no island in the

river, and then one day it appeared. There was no island. Then it appeared

small, and suddenly it was just there. Is that even possible?”¹ Seeing Bamseom

from the boat, I felt the same strangeness she described. Had I been the one

asking, I might have said, “What is that?” And if someone had asked me, “Is

that an island?” I might have answered ambiguously, “Well, maybe it’s an

island.”

The island carried such an uncanny presence that it was difficult to

pose concrete questions. On reflection, asking when an island came into being

or where it is located seems odd—an island does not usually appear and

disappear, nor does it move. Yet confronted with this strange presence before

my eyes, I could understand why the artist wondered when, where, and even how

Bamseom appeared. It was unmistakably there, and yet unclear.

Compared

to the album photograph shown in the opening scene and the clearly visible

figure within it, the island is far less definite. Still, just as the artist

begins a story with a single photograph, might even the most precise record be

subject to the same questions—at least when it is tied to memory?

Our

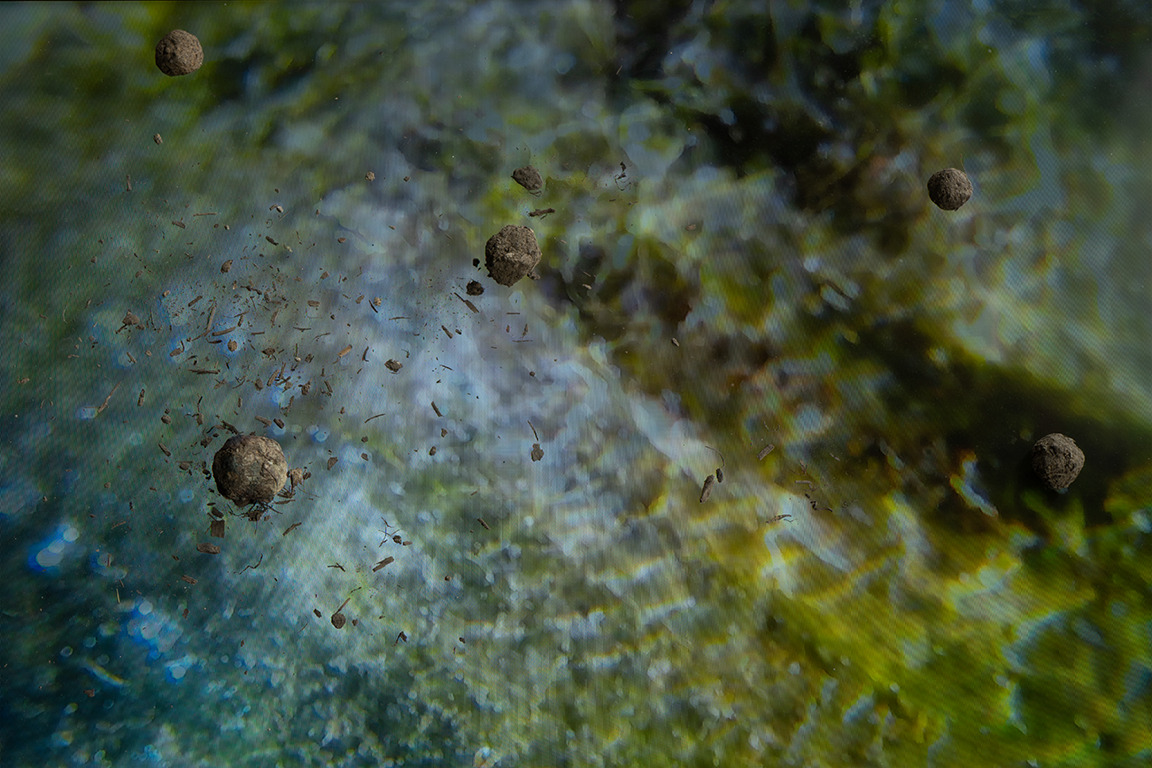

gaze toward Bamseom wavers between clarity and vagueness. When looking at this

island—blasted in 1968 and yet still remaining—whether glimpsed in passing from

a boat, lived on by former residents, seen only in photographs, or encountered

in person, the questions must be posed together, collectively. On the day Khym

and I took the cruise, people were looking at the 63 Building and the National

Assembly. These landmarks were far easier to recognize and far more visually

legible than Bamseom. Bamseom appeared simply as a mass of forest. Something

was clearly there, yet difficult to define.

It

had rained heavily the day before, and there was a chance the cruise might be

canceled. Thanks to the successful departure, we were able to see the island

that remains. Had the water level risen enough to obscure it, I likely would

not have given the island a second thought. In sedimented pasts—where record

and memory are mixed like muddy water—what lies beneath is easily overlooked

from the speed and position of a passing cruise ship. Whether record or memory,

everything that remains here is both clear and ambiguous. Bamseom prompts

questions about what this is—what kind of object it is—and what kind of

background, what kind of memory, it holds.

As

I continued through the exhibition, the title 《Blurry Dreams》 resonated in an oddly fitting

way. Memory is often likened to dreams, but is there anything as vivid as a

dream? If dreams are places where narratives are vividly shaped by concrete

experiences and thoughts, then what is a “blurry” dream? Perhaps it is something

that has been eroded or worn away from what once existed—and yet still remains.

Bamseom, as seen through Khym’s gaze, and the stories surrounding it, seem like

such a mass: a condensation of memory, record, and experience. It is there, and

yet it compels us to ask what it is—indeed, it leaves us no choice but to ask.

This

notion of a “mass” brought back my experience of opening the book Missing

Link(2024), presented in the exhibition. On the first page is a

photograph of an elderly man seen from behind, looking out a window through a

camera. When the gaze of a person looking outward forms a visual field through

a device, memory and record become inseparable from the experience of seeing

itself. As the pages turn, the image enlarges, gradually concentrating on the

head.

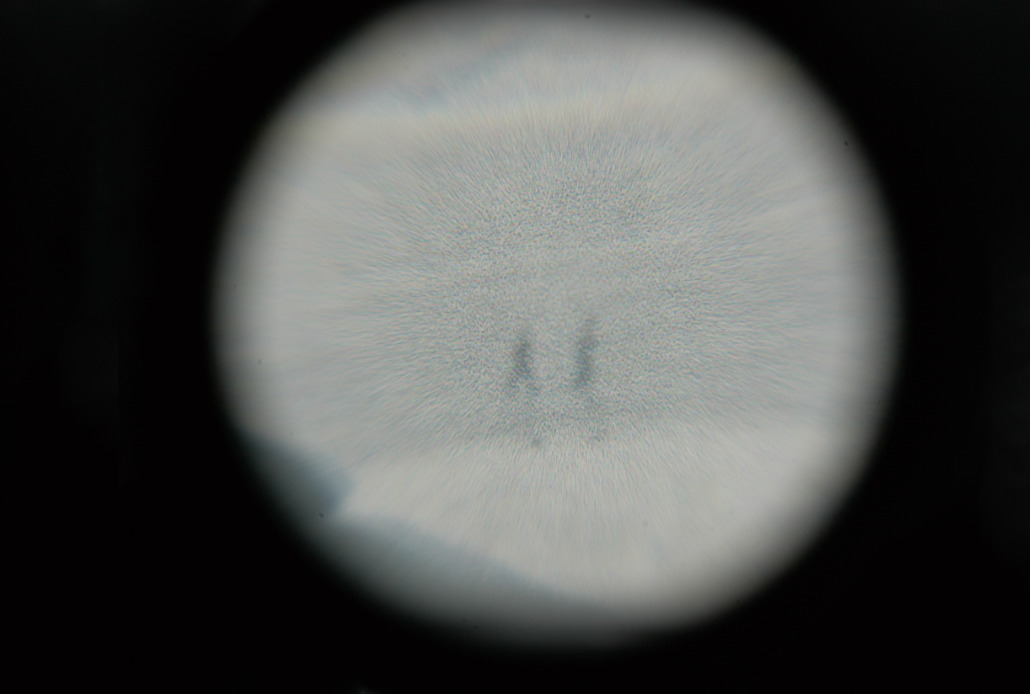

Then a mass appears. While this mass is likely a photograph of the “mud

balls” Khym has worked with since 2022, to me it resembled a head. The

experience of directing one’s gaze outward returns inward, molded into memory—a

record that can both coalesce and disperse. The head, as something that is not

clearly defined yet undeniably present, becomes a mass, resembling Bamseom.

If

memory and record are sediment, whether they surface or not depends on the

point of view—both visual and temporal—though in truth they move vertically,

rising and sinking. In gather, there is a scene showing

a bedsheet. Nothing appears on the sheet as people converse around a

photograph, and when the sheet is lifted to reveal what lies beneath, there is

still nothing. Has the island disappeared? Or has it not yet appeared? The sound

of flowing water continues. When we ask the person before us about what appears

in a photograph, the answer is grounded in memory. Bamseom’s identity emerges

as a condensation of ambiguity, mixed between the testimonies of former

residents, Khym’s memories, and the scenes recorded through her work.

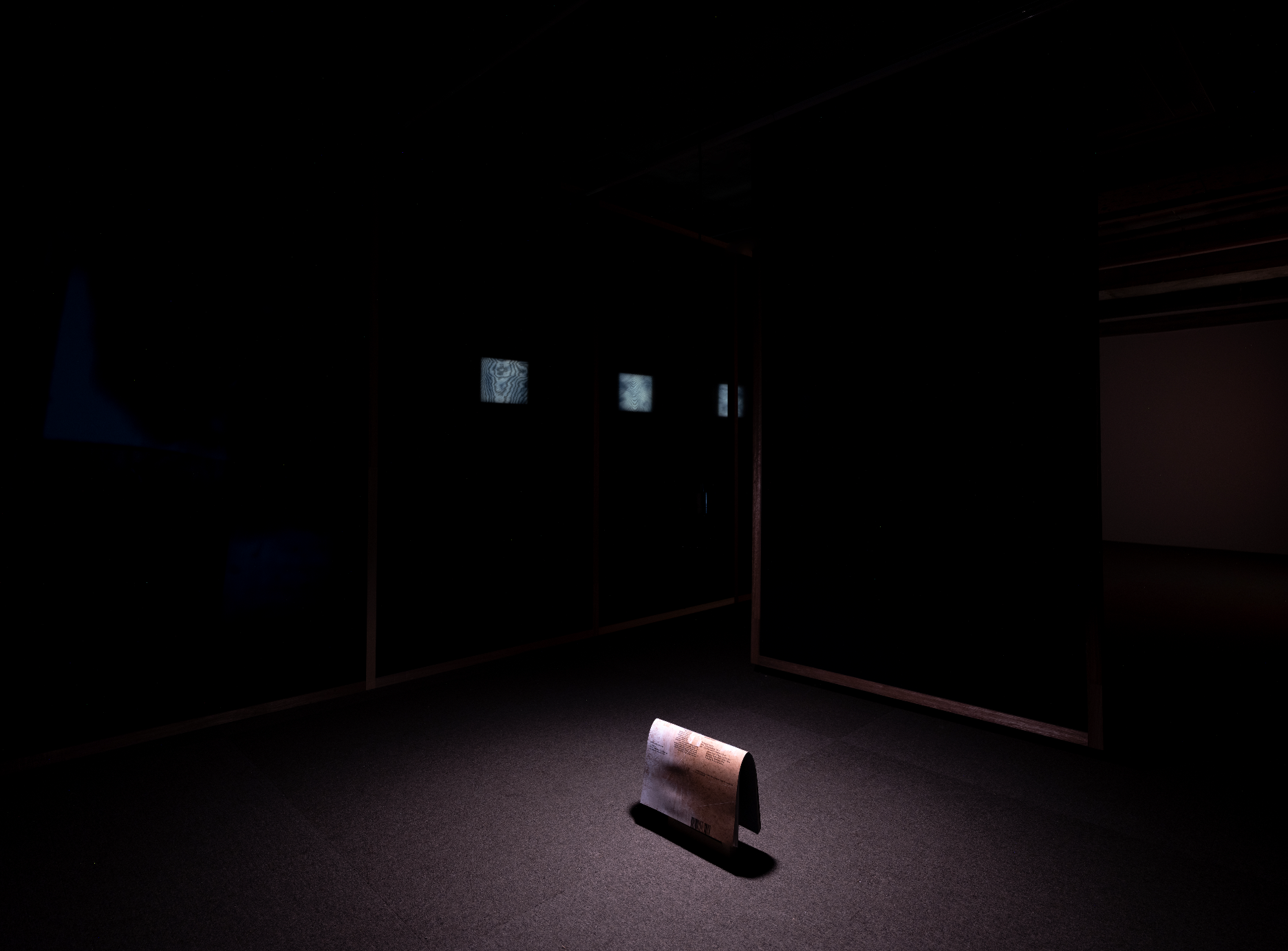

The

visual field formed in the exhibition space—divided by walls yet directing the

gaze beyond—takes shape in my own memory, much like the first page of Missing

Link. The reason the video scenes and photographic outcomes appear in

abstract forms is precisely because this is how Bamseom appeared to Khym. More

than that, it is an attempt to show that this is a definite mass containing

memory, record, and experience.

Her

gaze toward the island is directed toward the past. The images flowing from a

photograph Khym took of a former resident holding a camera—river and

memory—remain in the mind through the apparatus. Though outwardly unremarkable,

both Bamseom and the head are sites that remember and record the past. Like an

image that enters the video frame and remains still, like a camera obscura–like

exhibition space divided by walls yet allowing light to enter, images come

inside and linger—only to scatter again.

Even

if it appears abstract, there is something here akin to a “blurry

dream”—something worn down or refined. It is the residue of experienced pasts,

emerging from a gaze that horizontally connects memory, record, and experience.

It is not vivid, but it is unmistakably present.