At

one time, Impressionist painters captured outdoor landscapes on canvas. The

surface, reflecting the painter’s sensations shaped by weather and sunlight,

came to hold flickering impressions and momentary time. Such sensations—liable

to disappear at any moment—are also evident in Claude Monet’s ‘Cathedral’ series.

Over time, sensations that might vanish came to orient not toward sensation

itself, but toward substance.

The frame of the canvas, which once held fleeting

sensations reflected in the atmosphere, became the frame of the camera,

capturing moments when objects are destroyed or collapse. In Monet’s canvases,

architecture is born and dispersed as fragments of color alongside perception.

In the camera’s frame, by contrast, architecture waits for the moment when it

may disperse—a moment yet to come. Together with us—the photographer and the

viewer.

The

light that once flickered within the sunlit canvas does not scatter

instantaneously within the camera frame. Rather than illuminating the present

moment, it illuminates a moment that may occur someday. The development of

light that allows us to see distant things has also allowed us to observe

temporally distant moments. Only through this context can the reliability tests

and blasting videos addressed in Eunhee Lee’s solo exhibition 《Mechanics of Stress》 at DOOSAN Gallery Seoul

be properly understood. In today’s visual environment, light renders objects

present as images—so to speak, at the speed of light.

While blasting as a

subject easily evokes images of speed and immediacy, in the exhibited works

light captures not a rapid gaze, but a deep gaze. To analyze 《Mechanics of Stress》, the term “rapid gaze”

in the earlier description—“light that allows us to see what is distant, and

temporally distant as well”—must be replaced with “deep gaze.” A deep gaze

refers to penetrating the material–qualitative conditions inherent in objects

in reliability testing and blasting, and appropriating them as resources.

Material–qualitative

conditions are formed through a relationship in which the conditions of

materiality determine quality. The reliability tests and blasting addressed in

this exhibition reveal two aspects of such material–qualitative conditions. In

reliability testing, these conditions are derived by measuring the lifespan and

durability of the tested object.

In other words, through externally applied

impacts administered by apparatuses, we come to know the critical threshold of

an object’s quality. By contrast, blasting sites might be considered nothing

more than destruction—or rather, a negative loss from which nothing can be

produced once destruction has occurred. Just as experimental processes reveal

an object’s limits through machinery, blasting too may be regarded as exposing

the limits of the ground itself.

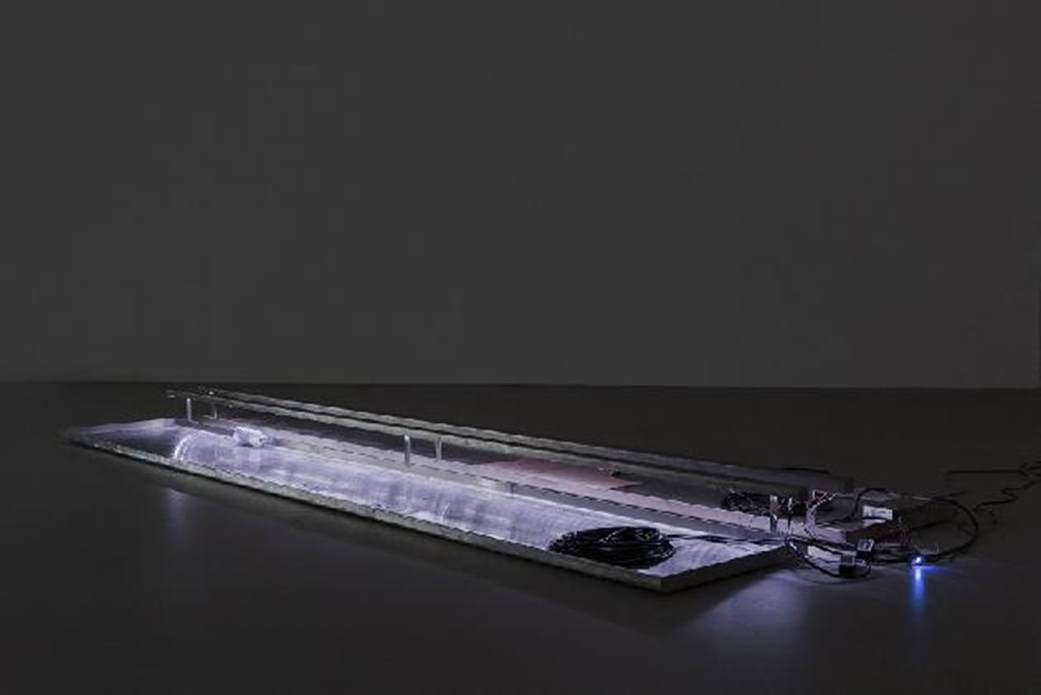

However,

as described in Mechanics of Stress #3 as an

“action” undertaken by engineering to address and resolve a problem,

material–qualitative conditions can update thresholds and negatives through the

action of human intervention. Blasting, used in infrastructure construction

technologies, constitutes the first step toward activating underground space

for human life. From the history of mines extracting coal as fuel, to urban

development, subways, and even fiber-optic cables forming global internet

networks, the underground embodies qualitative robustness that supports human

existence through its material solidity.

This is the material–qualitative

condition. Accordingly, the deep gaze is closely connected not only to

metaphorical outlooks, but also to directing attention toward physically

inaccessible spaces such as the underground. Within the frame of Eunhee Lee’s

videos, the viewer’s gaze turns toward underground space as “remaining land”—a

margin that, accompanied by additional resources and technologies, can enable

better living—alongside the temporal point of objects that have not yet been

destroyed, but may be destroyed someday.

From

this perspective, one might interpret Lee’s solo exhibition as drawing out the

literal “underside” of contemporary life through a deep gaze. We live without

knowing what materials constitute the objects we touch and handle, and without

awareness of the infrastructures behind communication environments; the

exhibition could be said to redirect attention toward these hidden conditions.

Yet the question to pose to such interpretations concerns the distance between

the deep gaze established as a condition of video documentation and Eunhee

Lee’s works themselves.

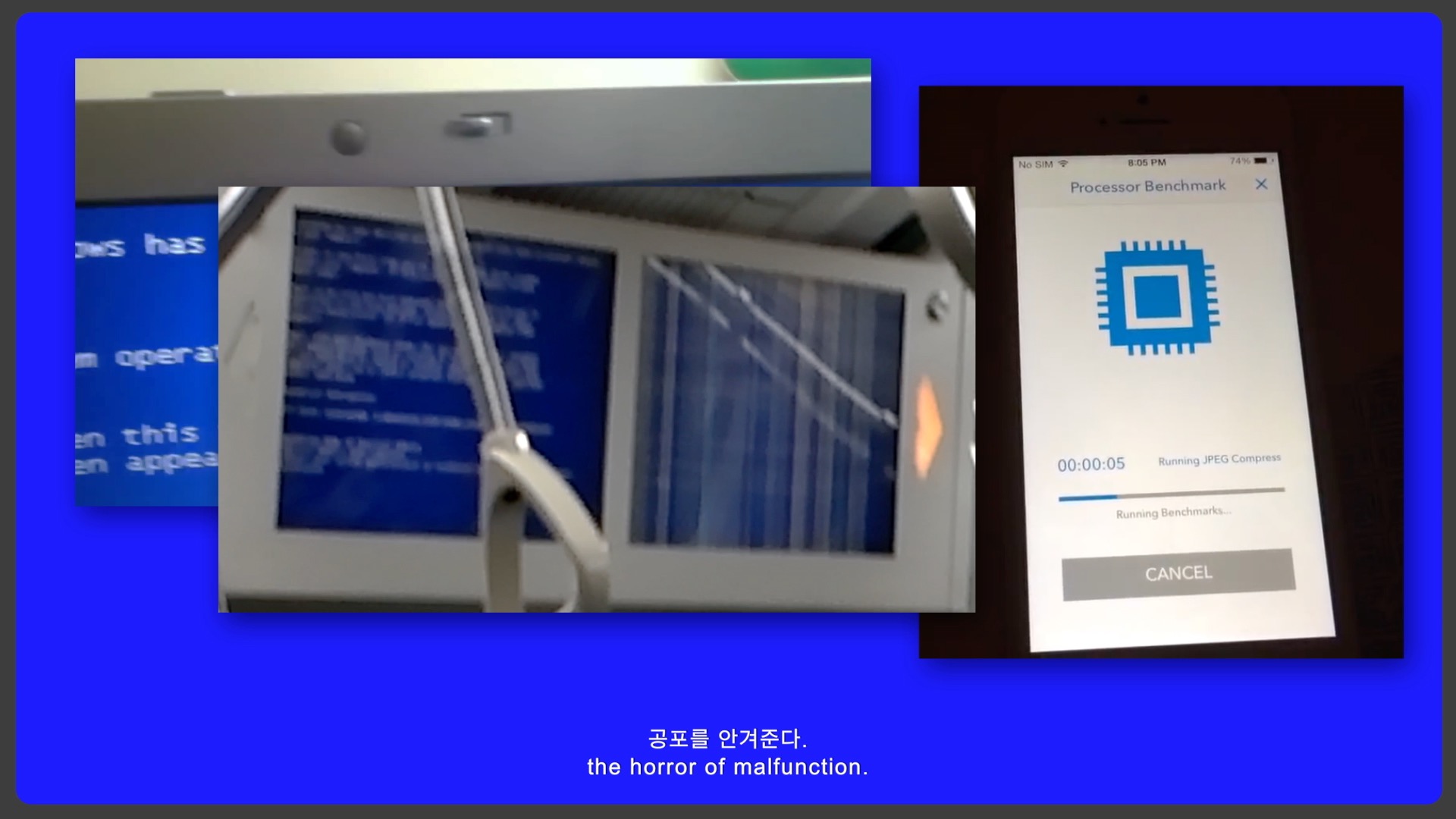

As surprise spectacles—like “Mentos and

cola”—proliferate, and as smartphones and CCTV systems produce continuous human

and non-human surveillance, gazes wait passively or actively to capture moments

that may or may not arrive. It is necessary to consider how Lee’s work differs

from these contemporary modes of video recording and sharing. As seen in

so-called “challenge videos” or prank videos, video documentation has become an

experimental space for drawing out hidden sides. In today’s visual environment,

frames contain moments that viewers wish to see more of, held within a

long-term outlook.

Such prospective or anticipatory attitudes form a cyclical

structure in which all video works circulate between post-production and

pre-production. Within this cycle, the critical point to be scrutinized and the

anticipated conclusion are already embedded. While a rapid gaze dulls sharp

awareness through mood changes or channel surfing, a deep gaze subjects its target

to persistence. Like planning and implementing land use in order to envision

surface prospects by preserving subterranean margins, it operates in a

post-productive mode. From this perspective, Nicolas Bourriaud’s question,

“What can we do with what we already have?” does not serve as an alternative to

the question, “What new things can we create?” The deep gaze binds

pre-production and post-production together in a continuous cycle.4)

Judging

by the materials she addresses, Eunhee Lee’s works can be understood as cycles

of pre- and post-production generated by a deep gaze. Reliability testing

refers to an engineering industry that categorizes and simulates external

stimuli a product may experience in order to calculate its lifespan or failure

rate.5) Environmental stresses such as temperature, vibration, and electric

current are applied to test durability, and in Mechanics of

Stress #1, these tests appear as images of objects that, fortunately,

have not yet been destroyed.

What is notable here is that before objects reach

the “fatigue limit”—the technical term reflected in the title—viewers perceive

the lights of measuring instruments attached to devices, fluctuations in

numerical values, and fragments of vibration as sensory impressions. What is

occurring inside the object cannot be known simply by opening the machine

unless one looks inside or destroys the object. In tests that track the

conditions an object can endure, its qualitative characteristics remain in a

state of doubt, becoming apparent as limits only when destruction occurs. More

fundamentally, viewers find it difficult to identify the object under test. It

is certainly an object—but precisely because it is an object, assuming a

recognizable form, its identity and function remain unclear as it undergoes

impact within the machine.

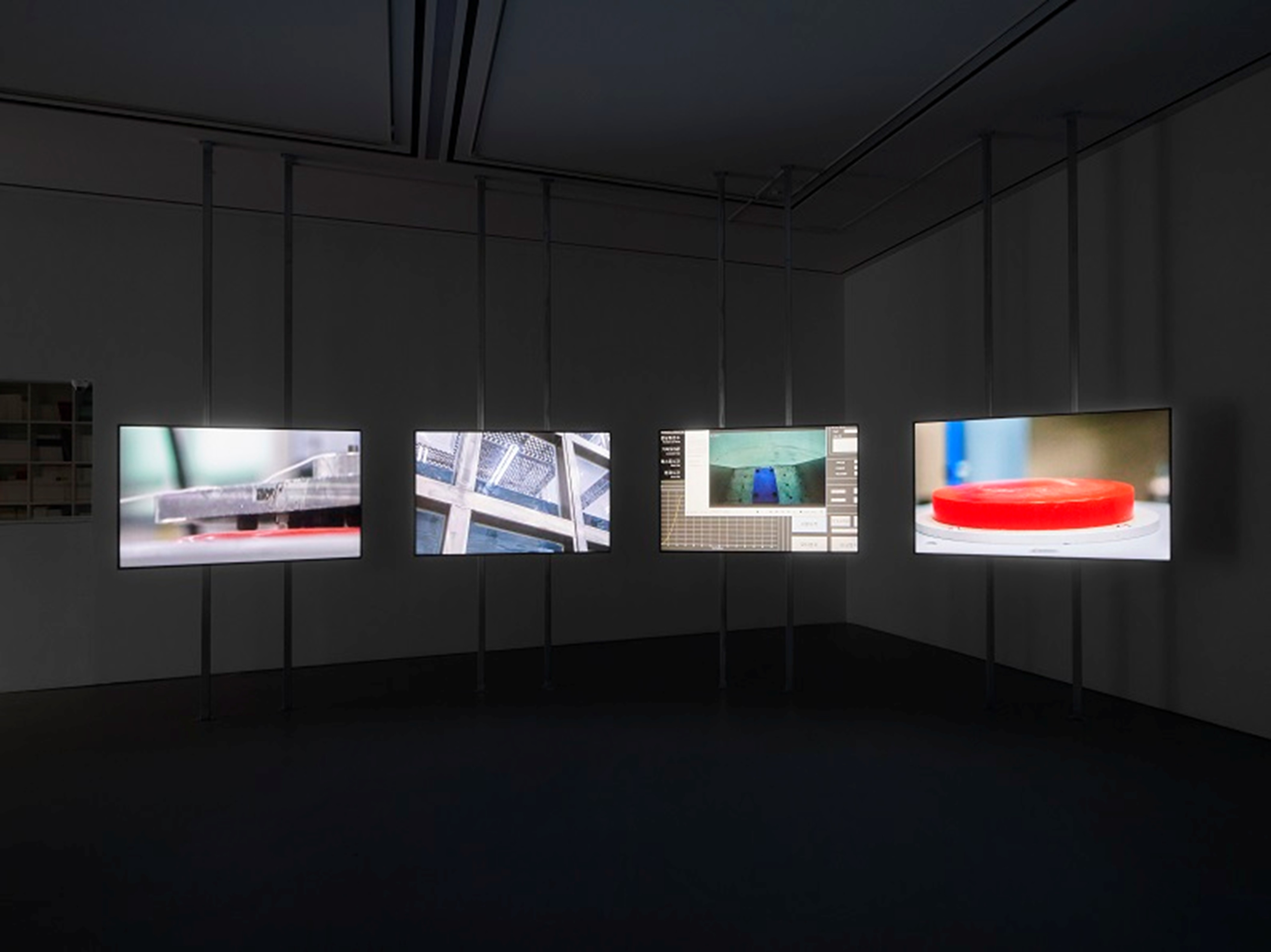

The

video documenting this testing process—where the object remains in

doubt—unfolds across four channels, capturing scenes of sound, water,

vibration, and detailed mechanical movements. Here, the deep gaze shifts into

momentary description. When qualitative characteristics are confined within

doubt, the deep gaze directed toward the object is blocked and becomes

descriptive. Although a test is being conducted on an object, its identity,

without destruction, disperses within the video frame as sensory, non-integrated

information.

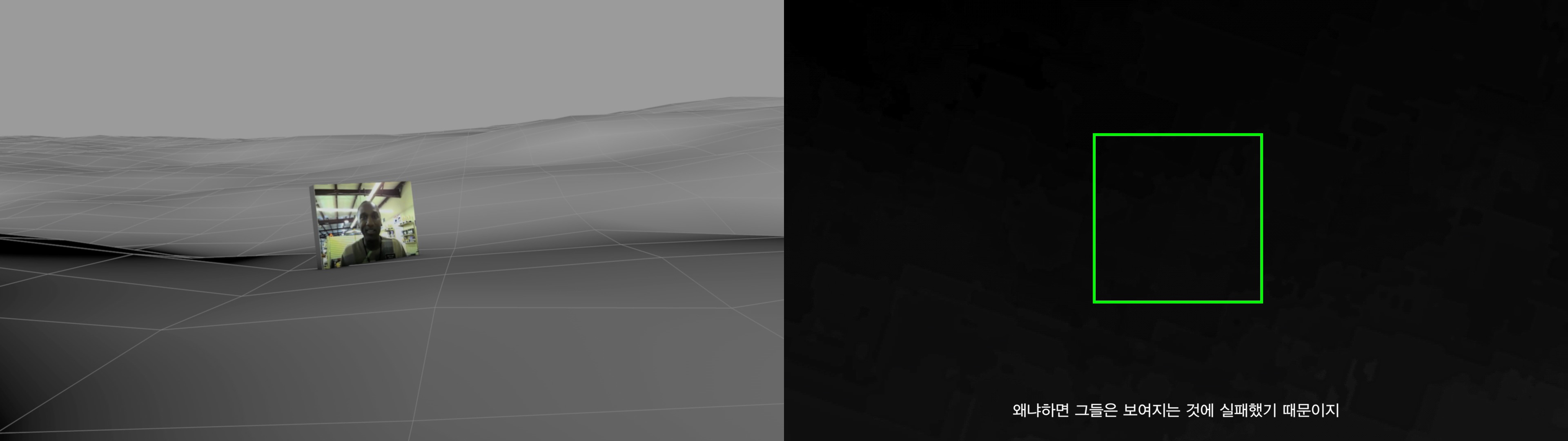

What

we can clearly discern in the exhibited videos are the fragmentary sensations

circulating around objects (in a broad sense, including underground spaces).

Laboratory vibrations, machine noises, illuminated buttons, and splashing water

disperse the viewer’s gaze toward moments that may precede destruction,

diffusing attention before the threshold of destruction. In this sense, Lee’s

video works share characteristics with Impressionist painting, where subjects

are constituted according to the viewer’s perception.

Just as Monet’s

cathedrals retain their substance beyond his visual field while his sensations

disappear, objects not yet destroyed scatter and recombine as fragmentary

sensations within frames documenting laboratories. Sensory information rendered

before a deep gaze flickers around the object. Rather than functioning as

frames that record moments yet to arrive, the works depict moments of sensorial

encirclement occurring before the viewer’s eyes.

Even

if blasting appears as destruction, it differs from loss in that it creates

margins. The outward eruption in blasting scenes serves material–qualitative

fulfillment of life on the surface, grounded in investigations of subterranean

material conditions. The smoke rising with the explosion sound at the end

of Mechanics of Stress #2 disrupts the cycle of

pre- and post-production pursued by the deep gaze, allowing us to witness, here

and now, that “screen”—once a canvas that held a fleeting moment—toward which

our senses had been drawn.

1.

See 1’50–2’20. Emphasis by the author.

2.

Rosalind Williams, Notes on the Underground, 1990; Japanese

translation: Chika Sekai: Image no Hen’yō, Hyōshō, Gūi,

Heibonsha, 1992, p. 71.

3.

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003; Japanese translation,

Misuzu Shobo, 2003, pp. 105, 116–117.

4.

Nicolas Bourriaud, Postproduction, p. 24, even though he referred to it as

an “artistic” question.

5.

See exhibition introduction.