Can

a machine die? This question has nothing to do with ontological questions of

whether machines are conscious agents like human beings, or moral questions of

whether machines should be perceived/ recognized as living things. It is more a

question of whether machinery can simply remain in the realm of valuelessness

when it stops working or loses its effectiveness because of some defect. This

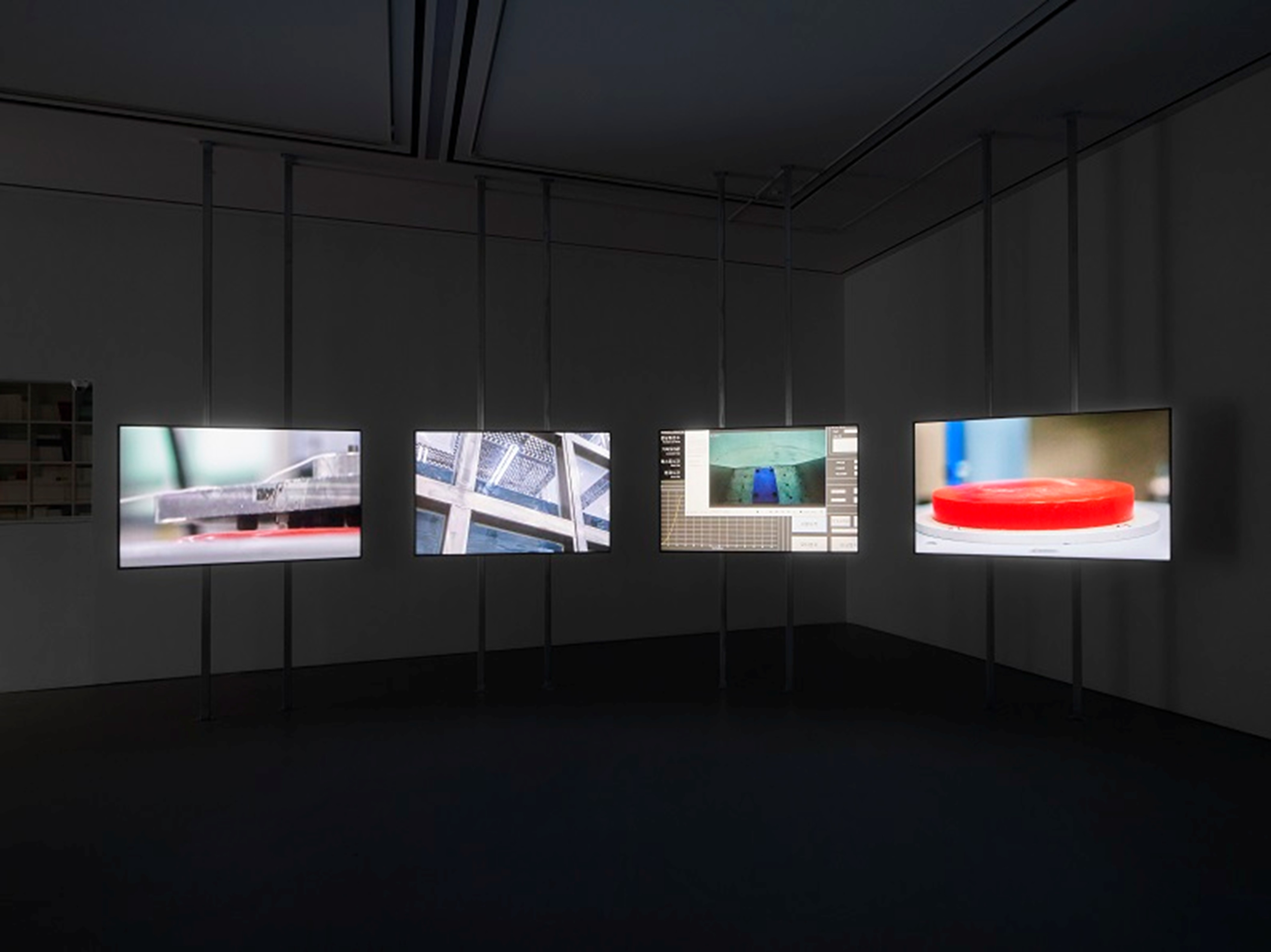

is both a preface and a conclusion for talking about Eunhee Lee's recent work HOT/STUCK/DEAD(2021)

and her latest work Machines Don't Die(2022). In the latter

case, the artist has already stipulated that “machines don't die."

But she

has not said that machines are alive. We don't ordinarily speak of machines as

being alive, but when a machine that has had some problems returns to normal

functioning, we might also speak of it as having "come back to life."

In other words, since a machine is obviously alive–or ought to be–we only

recognize that "life" when it is at the brink of death.

At

the start of HOT/STUCK/DEAD, the artist/narrator sees a hand

emerging from an electronic display panel on the street one day and is reminded

anew of the self-evident truth that "screens and images [...] must have

been made by a great many hands, [...] by complex hands." This too

resonates with the idea that a machine alerts us to its aliveness when it is

close to death.

The hand that pushes through the electronic display with its

partly dead panels is a defect that inhibits the normal functioning of the

medium/machine, and it is a flaw that explodes the premise of an automated,

autonomous machine. This human/hand, as dual flaw, is defective enough to be

described as a literal defect, yet it can only emerge through the normalization

process of fixing the flaws of a machine that is malfunctioning but not totally

ruined.

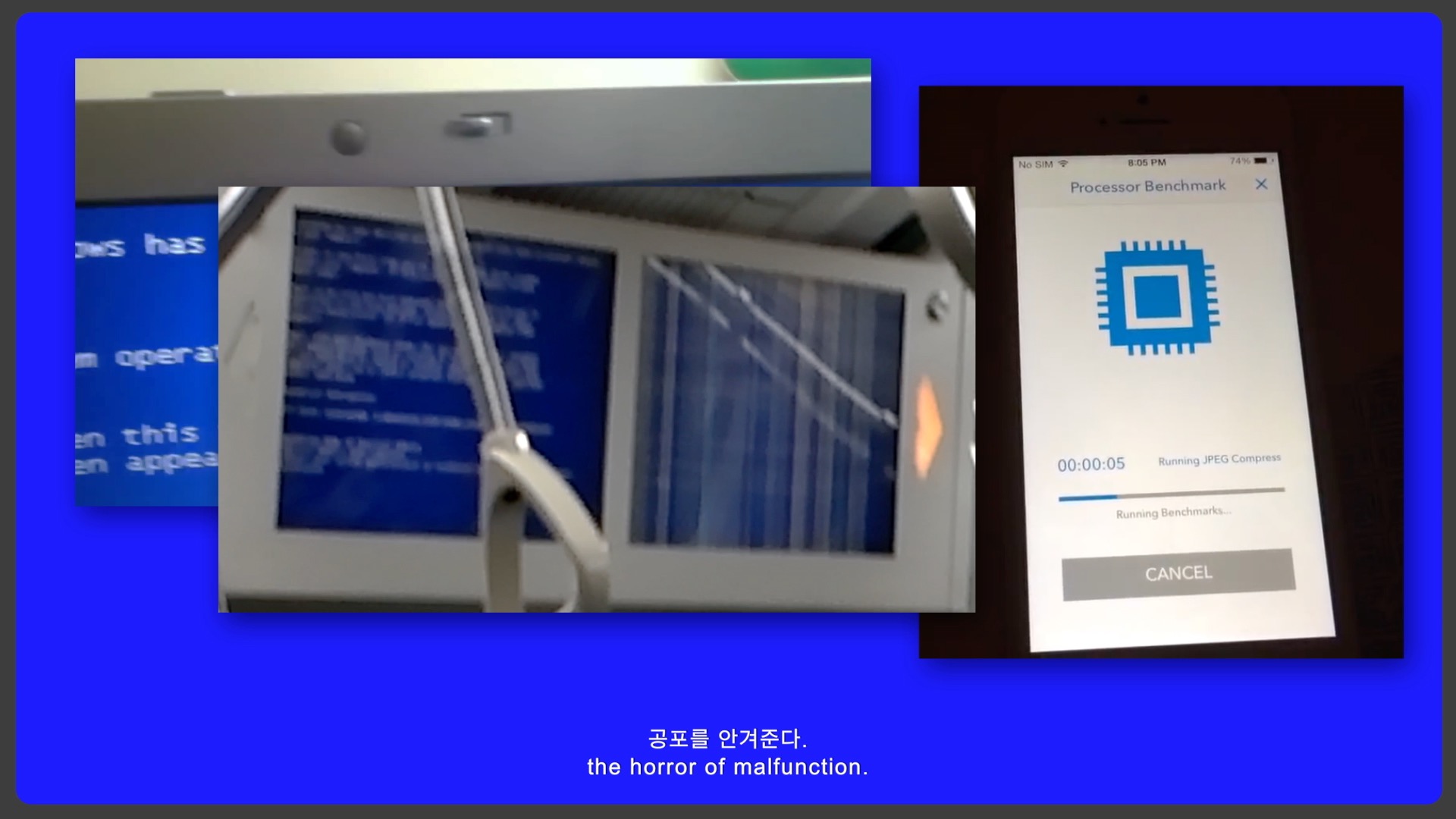

Midway through the work, for instance, a hammer wielded by the human

hand emerges as external noise/defect kills off roughly half the screen. The

defective image that pokes through the cracked screen and split surface can

still be mediated normally because the screen/machine continues to function; in

this sense, it indirectly illustrates the normal nature of the medium and the

physical limits and material nature of the medium/machine.

Conversely, the end

of the work shows that when noise fully transcends signals and defects fully

transcend normal functioning, defects no longer appear as defects. As the

screen ruptures, what is revealed is not a (defective) machine that has almost

died but remains "alive"-all that remains is normal debris,

consisting of glass and metal fragments and a fluid that emits an acrid stench.

When

a machine has become a pile of waste, we obviously cannot say that it is not

dead. Yet it seems absurd even to refer to a dead machine as a

"machine." The machines that emerged with the dawn of industrialism

were automated devices created from the outset to maximum production efficiency

and profit. In that sense, they must be kept in an autonomously complete state

for maximum gains; any defects that could inhibit production or bring them to a

halt must be ruled out or subsumed.

In a word, a machine is only a machine when

it operates ad infinitum–when it does not die. The defects that have to be

ruled out or subsumed for the machine to live on eternally do not just include

things like rust or misalignments on cogwheels. They also include flaws in the

products that the machines give life to, and flaws in the people who gave life

to the machines. This is borne out by the calibration features and screen

savers that nearly all screen-based machines carry to prevent or minimize

display flaws. The defective images they project hold no value in terms of

information or meaning.

Their value lives in preventing or reducing

sickness" for the screen-based machine, and as screen technology

advancements obviate their functional role, they are eliminated, or they end up

having to prove their worth through their entertainment role (the most

"useless" of all). Moreover, the first defects to be ruled out are

the passivity, inefficiency, and instability associated with the human beings

who create the machines. The human being and human labor can only be subsumed

when they are transformed into part of the machinery, an ancillary process in

the machine's function, or a mechanistic presence in their own right (laboring

"like machines" or transcending "normal" humanity through

the additional of mechanical elements).

For instance, if the panels on the LED

display were all dead, the human hand that the narrator encounters could not

have been able to tear through the image and screen. As a result, there would

have been no moment of recognition through the rupturing of the

"reality" of machinery, as represented by the "complex

hands." Had it remained simply scraps of metal rather than a machine that

had only partially died out, all that would be shown there is the image of

people working to dispose of it, or simply working, without it being mediated

in terms of any value or meaning. (Or, more likely, it would not be shown at

all, covered up by screens like most of the production and disposal processes

in the city.)

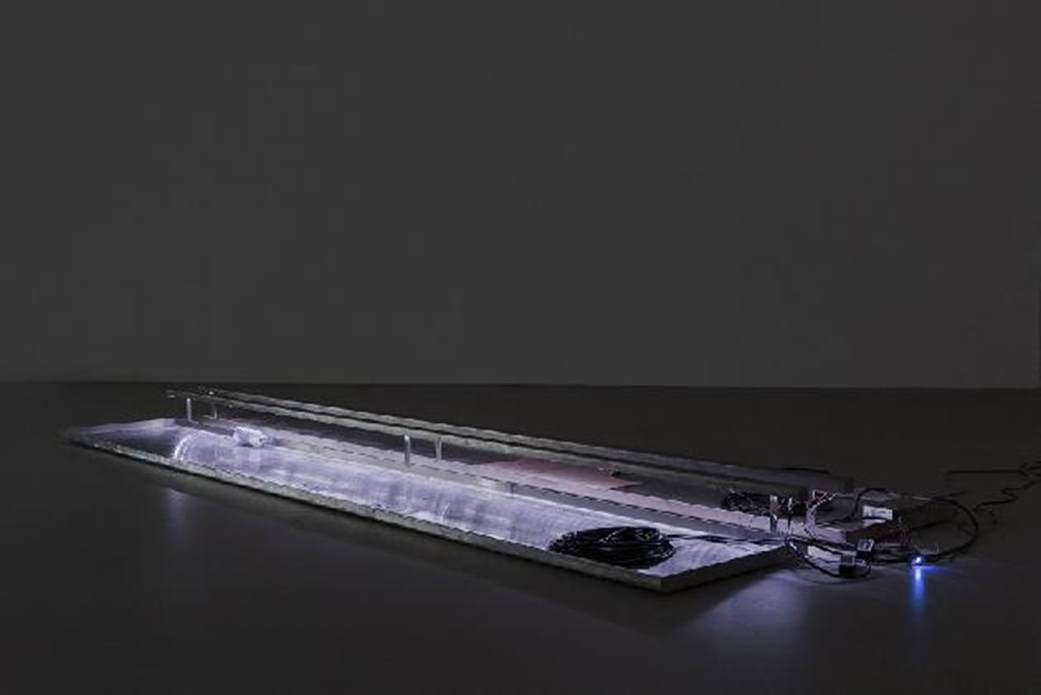

The

partial death of the screen/machine and the resulting awareness of the

machine's life leads automatically into an exploration of ways of reviving the

screen. Amid this examination of the screen's material and physical composition

and principles for the sake of its restoration, the liquid crystal of the

screen takes on the essential quality of a "topological defect structure,”

and it emerges that all screen/machines have a sort of functional shelf life,

where their luminance necessarily degrades over time. This seems to demonstrate

how all screen/machines are intrinsically flawed and bound for death.

But just

as the normal operating mechanism of the screen involves applying stimuli to

disordered liquid crystal substances to arrange them in the intended sequence

to project an image, the machine operates by overcoming or appropriating its

own death. The only time the blackness of death is granted to the screen is

when it should not be displaying any image. In the same way, the death of the

machine is granted when it becomes more efficient to replace it with a more

normal machine; as the repair worker says, “‘Repairing' a screen is a

lie." Obviously, this means the death of one machine, but it raises the

immediate need for another living machine.

In that sense, it leads to the

propagation of machines and the maximization of overall profit through

machinery. This shares echoes with the various events where the companies and

developers working on the front lines of cutting-edge digital machinery

production unhesitatingly share examples of technical defects and failures

rather than attempting to conceal them. In machinery and the machinery-based

society (a world used more or less equivalently to "economy"), things

like errors, failures, defects, and valuelessness are simply incorporated into

the process toward creating more normality, more value, and more profit; they

are not confined simply to the realm of death.

In

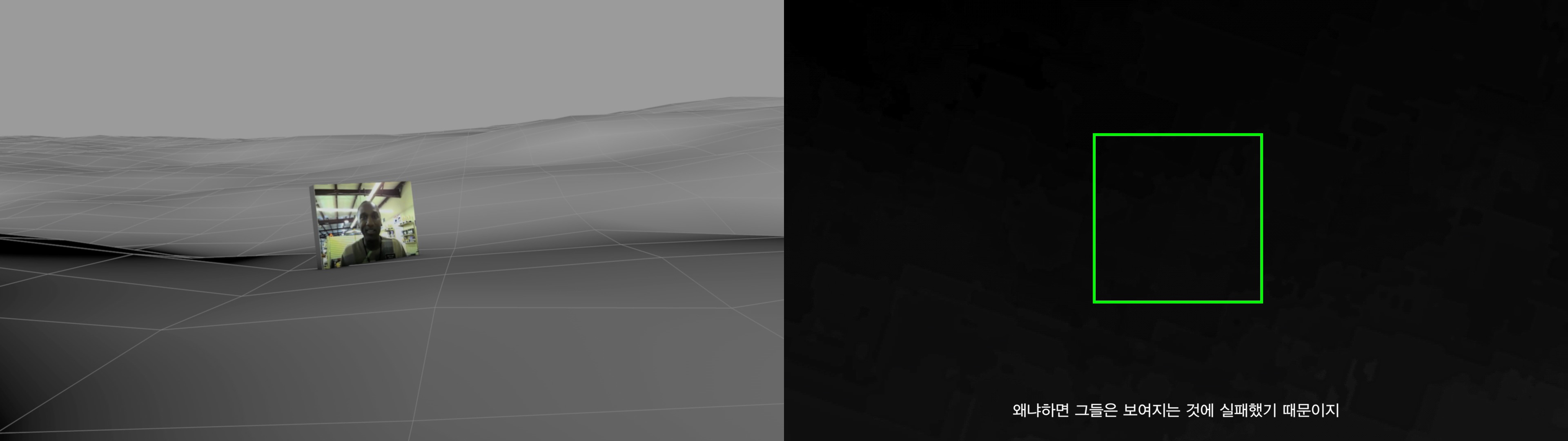

the end, the machine cannot die. Machines Don't Die depicts

the process of machinery's revival and rebirth–fated never to die as the

components of discarded devices are reduced to the purest minerals/goods. In a

similar way to defective substances that were never before treated as minerals,

only for their value to be discovered later as rare earth elements, the waste

machines that people once had to pay money to dispose of now negate their own

deaths as they are finely ground and burned to cough up the rare earth elements

concentrated within them.

The defects that are incinerated here include not

only the uselessness of the waste machine, but also the consumption of profits

in the form of wasted time. It is more efficient in terms of time–and by extension

profit–to repurpose the concentrated minerals present as available resources in

machine products than it would be to extract and process new minerals for use

in products.

Urban mining, which has the aim of achieving "zero

waste," succeeds in cleanly condensing the long process leading from

resource extraction to machine production-and thus in flattening the volume of

the biggest defects in capitalism, namely the waste of time and profit. Here,

there is no such thing as death or a dead machine.

But like the repeated

pushing and pulling of a timeline bar in a production process, like an endless

loop playing on fast forward, the machine is trapped in an eternally undead

state, forever alternating between its form as broken waste and its form as

something separated into different components just before production.

As

the pompous pronouncements of "making everything into resources"

suggest, the immortality of machinery based on the acceleration of time and

revival must have the ability to resuscitate all the defects of the capitalist

society in the form of profit. This is borne out by the urban mining process of

re-resourcification, where the defects among the defects and waste among the

waste must still be winnowed out, left as plastic machine parts condemned to

burn up in black smoke. In Machines Don't Die, images of machine waste from

which any remaining has once again been extracted are interspersed with images

of stalactites, products of the accretion of countless years on Earth.

The

images of two seemingly opposing objects, the most artificial products and the products

of nature itself, intermingle as the typical outward manifestations of

datamoshing that arise through the feedback and recycling of digital

images–condensed as codecs for easy use and fast processing of large amounts of

data– into another process of condensed encoding. The "flawless"

world of analog and digital machines is constructed through the availability of

the Earth's condensed time with its accretion of organic and inorganic deaths,

compressed in accelerating ways.

As it endlessly sends its own defects into an

automated feedback loop of profit-making, it produces fatal external glitches.

As this global system of profit feedback revolves ever faster–bringing even

death back to life–irreversible degrees of randomness shorten humankind's

remaining time at breathtaking speeds.

The

conclusion that Eunhee Lee is attempting to ultimately achieve in her work is

not some final judgment, where she is saying that because machines do not die,

humans do not die either, so that human beings and machines alike will soon

meet their deaths. Just as the defective images on the screen are products of

mediation by a screen that is not yet fully dead, the terror caused by global

defects and a contemporary apocalypse is another "defect" that allows

us to see the shackles of capitalist profit generation, which has not yet fully

collapsed either.

The fear of death evokes a longing for endless life. The

tired desire for immortality has merely been replaced by the tireless drive for

more living things, more new life, and by the eternal adage "live

today" that (we are deluded into believing) will be achieved through this.

"Malfunction and failure are not signs of improper production," it

has been argued. "On the contrary, they indicate the active production of

the ‘accidental potential' in any product." 1

The defect of undying driven

by machinery/capitalism and the defects caused by our attempts not to leave

behind any flaws may have the potential for value and meaning at an unintended

level beyond profit and goods. In the past, Eunhee Lee's art visualized the

defects of "normal things" maintaining their position of

"non-defects" by means of obvious defects. Now we look forward to her

future explorations. As Paul Virilio and Sylvère Lotringer said, "Failure

is failure," and "Failure is an accident." 2

1

Rosa Menkman, The glitch moment (um) (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures,

2011) 26

2

Sylvère Lotringer; Paul Virilio, The Accident of Art (Los Angeles:

Semiotext(e), 2005) 63.