On

August 9, the Gender and Labor Health Rights Center of the Korea Institute of

Labor Safety and Health (hereafter, the Gender Center) screened director Eunhee

Lee’s films Machines Don’t Die (2022) and Colorless

and Odorless (2024), followed by a GV session. This is a

reflection on that event.

Do Not Film the Workers

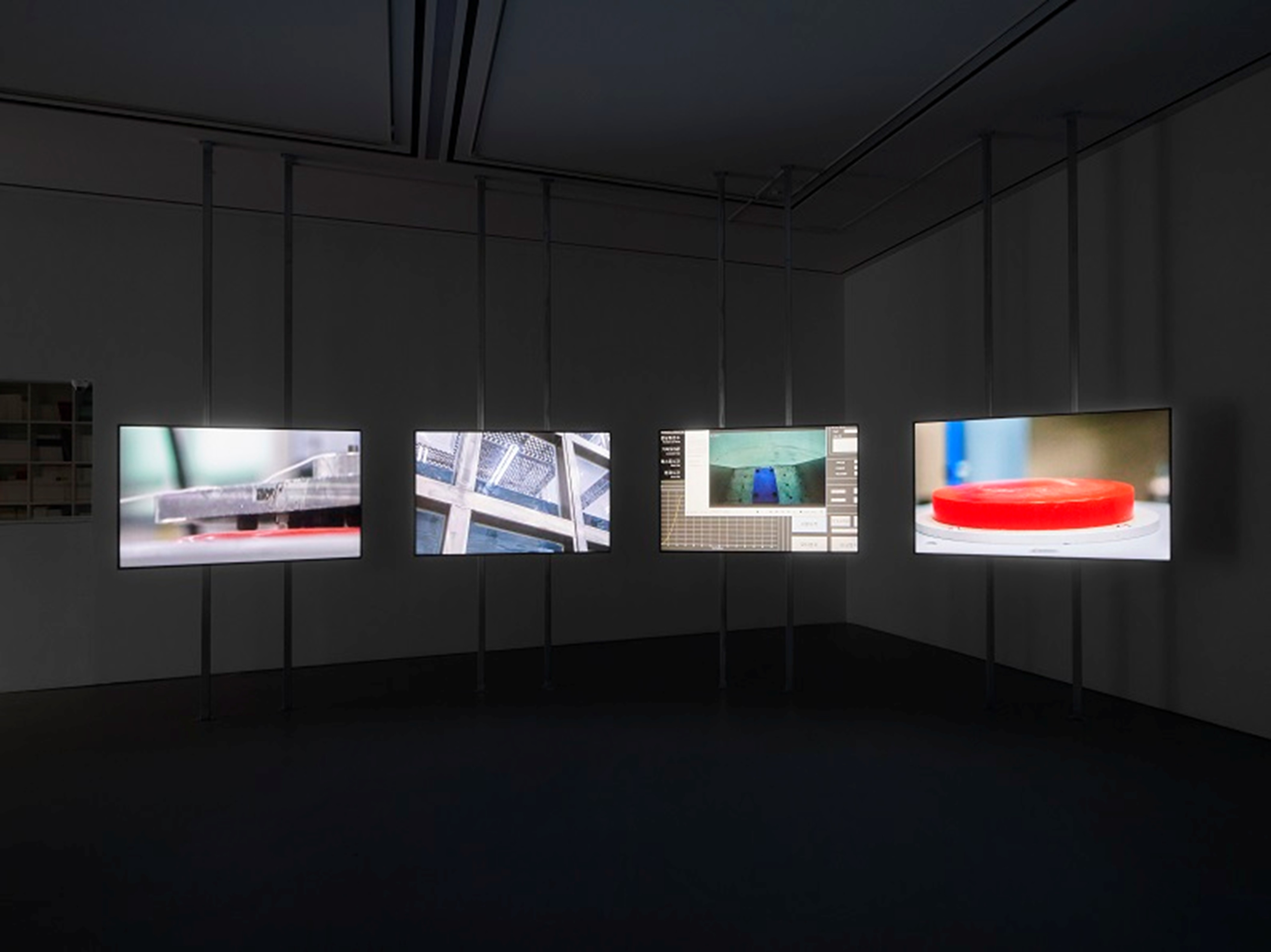

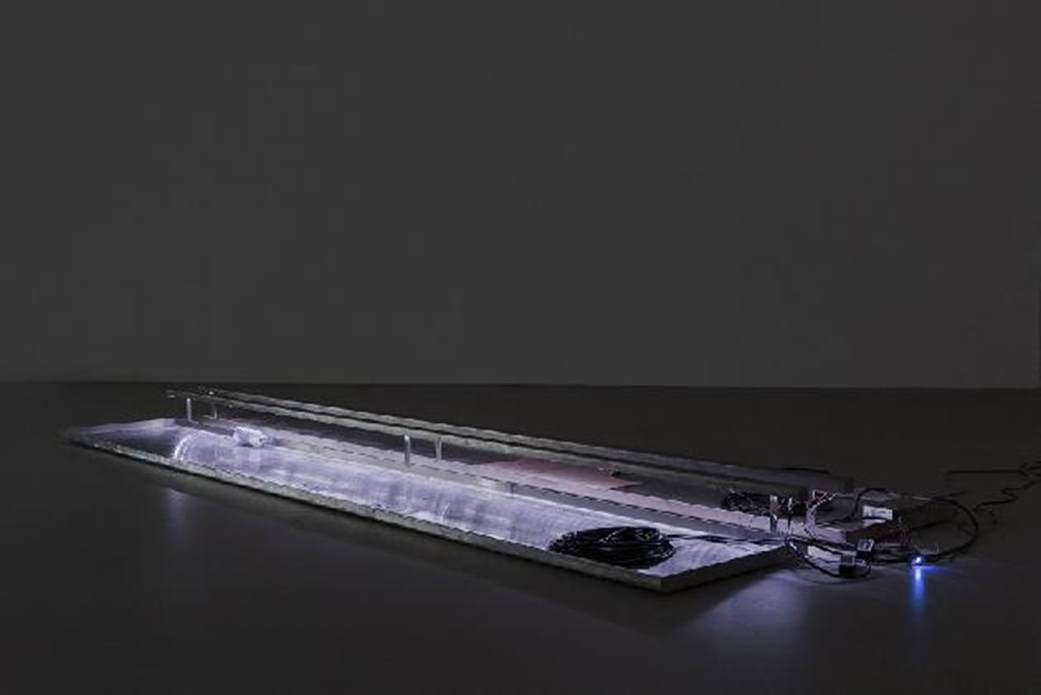

Machines

Don’t Die shows the process by which electronic components that

have outlived their usefulness are recycled through the waste-processing

industry. Mobile phones with shattered LCD screens, outdated

computers—electronic devices once familiar to us—are crushed into pieces in

recycling plants, where necessary elements such as gold are extracted.

Here,

the concept of the “urban mine” appears: just as glittering minerals are mined

from the earth, essential elements are extracted from electronic devices

discarded as urban waste. The narrator speaks proudly of “zero waste,” yet the

film presents visual evidence that waste and wastewater still remain in the

recycling industry, making “zero waste” an unachievable ideal.

Director

Eunhee Lee has said that she was initially interested in physical machines and

materiality. However, she also recounted that when filming waste-processing

plants, including during the production of Machines Don’t Die,

there was a recurring instruction directed at her: “Do not film the workers.”

When she shared this remark during the GV session, an audible sigh spread among

the audience.

In

the footage of waste-processing factories in Machines Don’t Die,

workers barely appear. The near absence of working bodies feels strangely

natural, reflecting how we fail to sense labor at all when we encounter

products. This is not a phenomenon unique to Machines Don’t Die,

but when filming factories, Lee explained that if people had to appear on

screen, they were required to wear full protective gear that they would not

normally wear, in order to obtain permission for filming (the safety warning

signs shown in the film are strikingly clean, creating a sense of incongruity).

Lee said that the people she encountered while filming these sites remained as

a kind of moral debt to her. This ethical concern regarding stories of people

continues in her more recent works, Colorless and Odorless and Seomseomoksu (2025),

which address labor and industrial accidents in the electronics industry

through the voices of workers who are also victims and activists.

Smells That Do Not Carry Across

Machines

Don’t Die features aqua regia (a mixture of nitric and

hydrochloric acids) that dissolves “everything.” This substance, which

dissolves anything it touches, is extremely dangerous, yet the acrid smell that

instinctively makes one recoil, and the sensory awareness of accident risk,

cannot be transmitted beyond the TV or cinema screen.

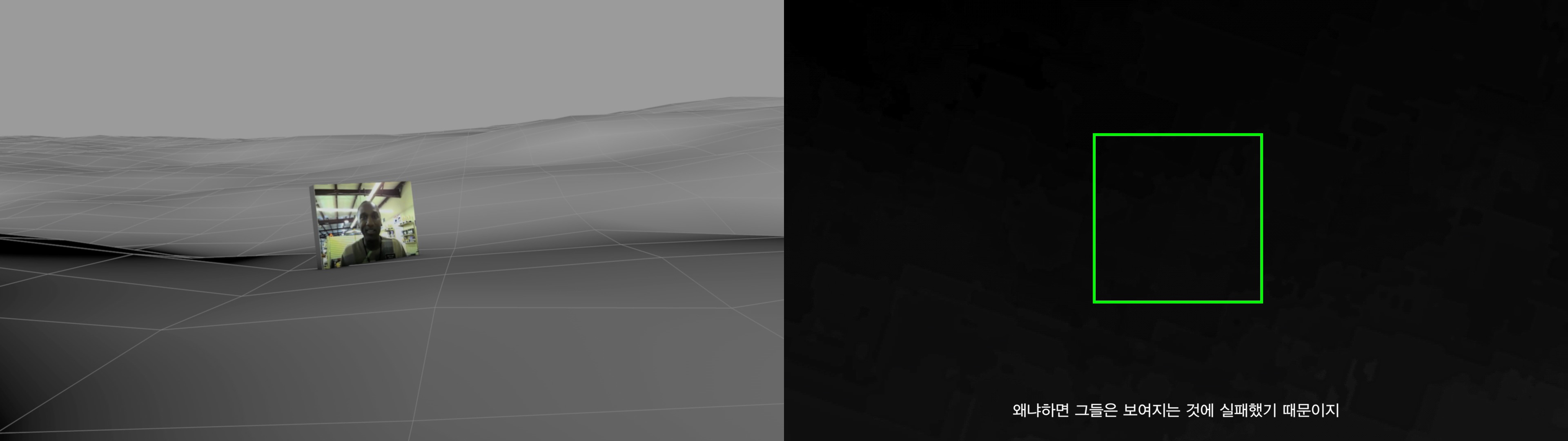

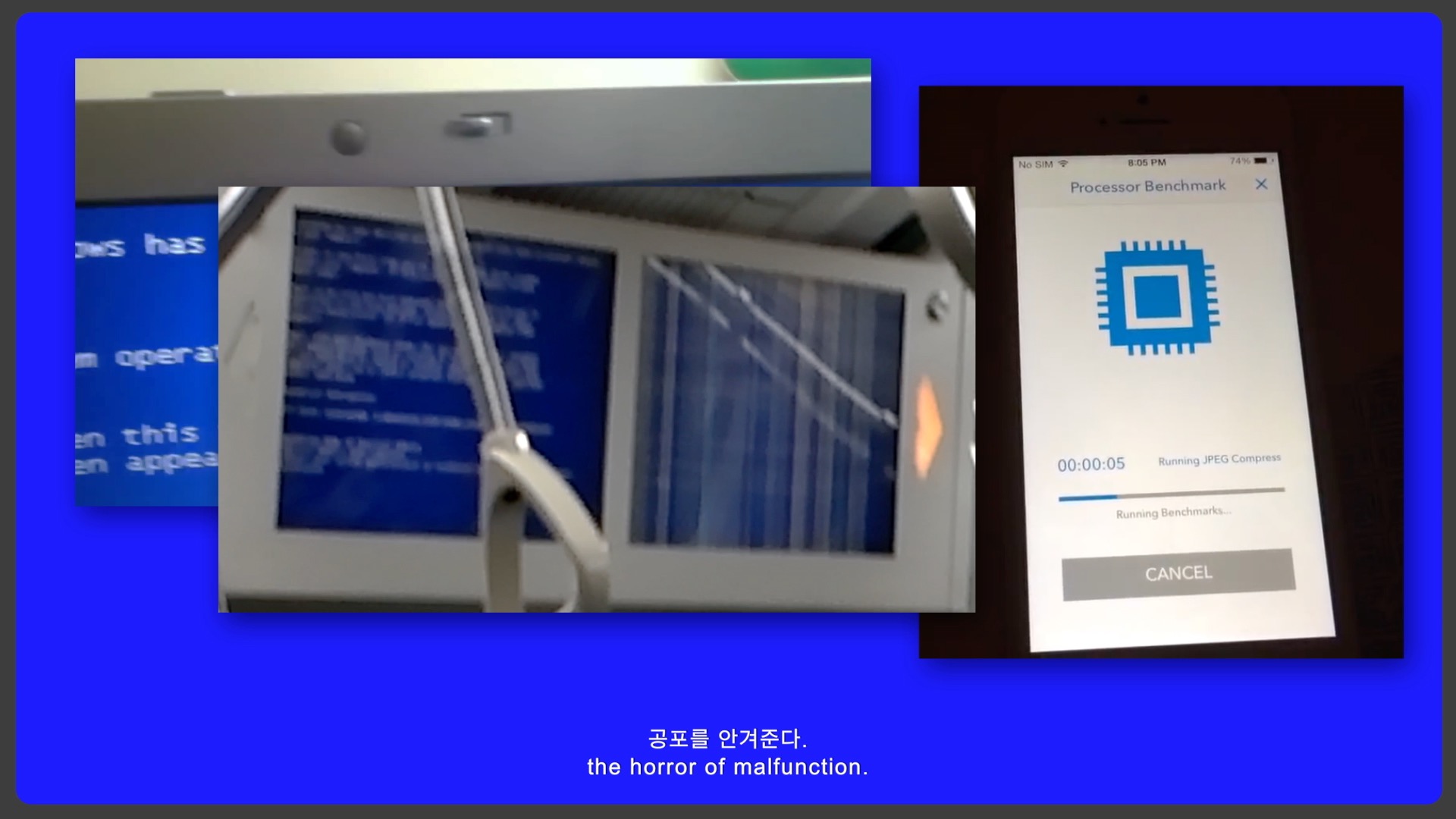

Both Machines

Don’t Die and Colorless and Odorless bear

traces of reflection on the limits of what visual media can convey. Some

sensations are perceived through the skin or nose before they can be explained

in words. Film is a medium limited to sight and sound. To approach the

transmission of these other senses, the films intermix distorted images,

altered colors, and visuals that feel vaguely nauseating.

Colorless

and Odorless opens with a handwritten “clean note” (a work log

notebook specialized for contamination prevention) bearing the name Hwang Yumi.

From beginning to end, the film follows records of “people.” Early in the film,

a worker who had worked in a semiconductor cleanroom recalls being fascinated

by wearing “the protective suits seen on TV,” but then states that inside the

process there was a “pervasive chemical smell” that television never showed.

Television

conveys only sight and sound, amplifying some sensations while discarding

others. The image of a pristine cleanroom and the corporate pride of Samsung

are excessively conveyed through media. Sensations that do not translate into

money or profit are discarded. Environments where adequate costs for safety

were not paid, and production lines that had already produced many cancer

patients in the West before relocating to Asia, were nowhere to be seen. Those

traces were instead etched into workers’ bodies and memories, their lives, and

their families.

Industrial and Environmental Disasters, and the Electronic Devices

in My Hands

These

stories could have been mine, or my family’s, or those of the region where I

live. RCA, cited as an example in the film, was a major American electronics

and telecommunications company. After struggles over severe environmental

pollution in the United States during the 1960s, it relocated its factories to

Taiwan in the 1970s.

At the Taiwanese RCA plant, not only were workers exposed

to toxic substances, but dormitories and groundwater around the factory were

also contaminated. More than 1,000 workers developed various forms of cancer.

Rather than reciting statistics, the film conveys the voices of survivors who

became activists: dreaming of a particular person for two consecutive nights

meant that person would die soon; the constant fear of discovering one had

cancer.

The

electronics industry knows no borders. In addition to RCA, the film includes

testimonies from workers who supplied companies such as Apple and ASUS.

Countless forms of labor went into transforming raw materials into these

products. The labor and pride of women workers in the electronics industry,

along with severe menstrual pain, miscarriages, and impacts on children’s

health. If, every time we bought these products, we had to fully bear and sense

the memories of industrial and environmental disasters, would they still sell

as they do now? The film insists on recalling the sensations and memories

erased by capital and by structures that trivialize the ill health of women

workers.

Even If Seen Less, As My Own Story

In Colorless

and Odorless, activist Kwon Young-eun of SHARPS (Supporters for the

Health and Rights of People in the Semiconductor Industry) reflects on what

kinds of experiences draw public attention. She notes that people have tended

to respond more to cases involving greater pain and longer suffering. Yet she

hopes these stories will be understood not as someone else’s suffering, but as

“my own story”—shared by all of us who use electronic devices, as neighbors and

implicated individuals—even if that means they are seen less, at least for now.

Jung

Hyang-suk, a former Samsung worker diagnosed with a rare disease and now a

SHARPS activist, recalls how she used her salary to enjoy “eating good food

with her child,” traveling, and how she “liked” those aspects of her working

life. These are sensations everyone shares, yet certain workplaces impose far

greater risks on workers without informing them. All of our lives are indebted,

in part, to hidden risks and illnesses. I take into myself that shared

wish—that while working diligently, neither my life, nor my family’s, nor my

children’s lives be damaged by unseen dangers.