The

world keeps telling us to do something. Do not lie down—get up. Do not stand

still—walk. It is better to run than to walk, and if you are going to run, it

is better to go faster. The list of things one must do never ends.

The

philosopher Bernard Stiegler distinguishes between “employment” and “work.”

Both terms differ from their conventional usage. Work, first of all, is an act

that increases knowledge through accomplishment. Work is an expression of

knowledge and is closer to an act of existence. Employment, by contrast, is

different. Through employment, as people come to work, they become alienated

from their own work.

Stiegler argues that in the early nineteenth century,

machines replaced humans and work left the hands of craftsmen, and that over

the subsequent two centuries of capitalist development, knowledge gradually

became impoverished. He insisted that we must escape employment and reclaim

work. The actions taken to reclaim work, he said, generate various things—unexpected

things, things one could never have dreamed of. If employment is entropic, then

work produces its opposite: something negentropic.

Work

or employment. Turning these two concepts over in my mind, I thought of the

museum. The moment one enters the white cube, there is something to be done.

One must follow what is placed in the space, pay attention, and concentrate on

analysis. In a way, what we call “aesthetic contemplation” is not a quiet,

inwardly沉잠ing activity but rather a busy and noisy one.

In museums, I have always felt that I must do something and that I must look

more meticulously. The museum is a ritual space separated from society. Yet

even here, the command to do something continues to operate. Entropy rises.

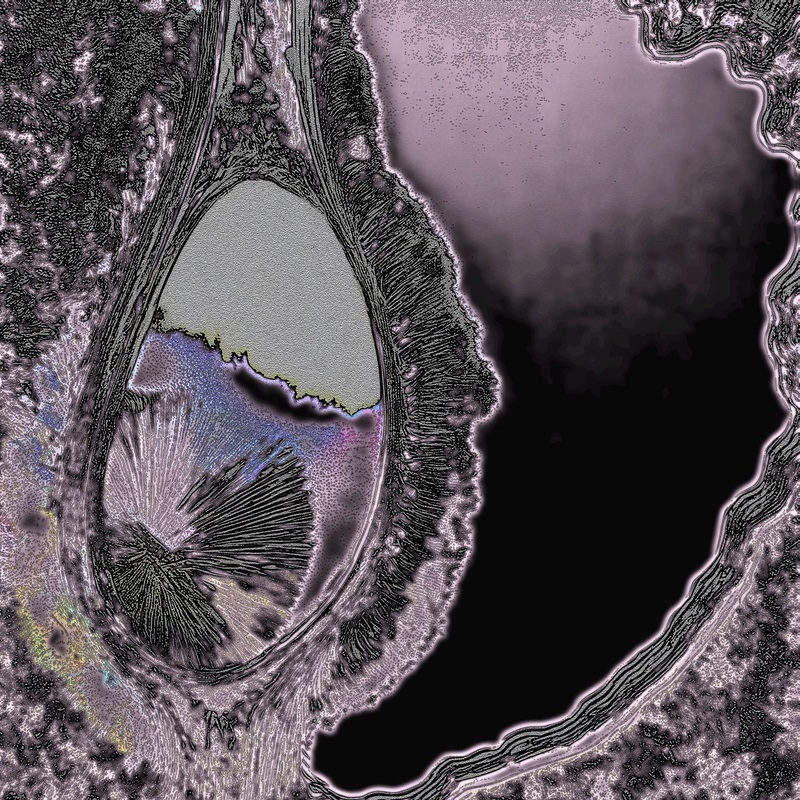

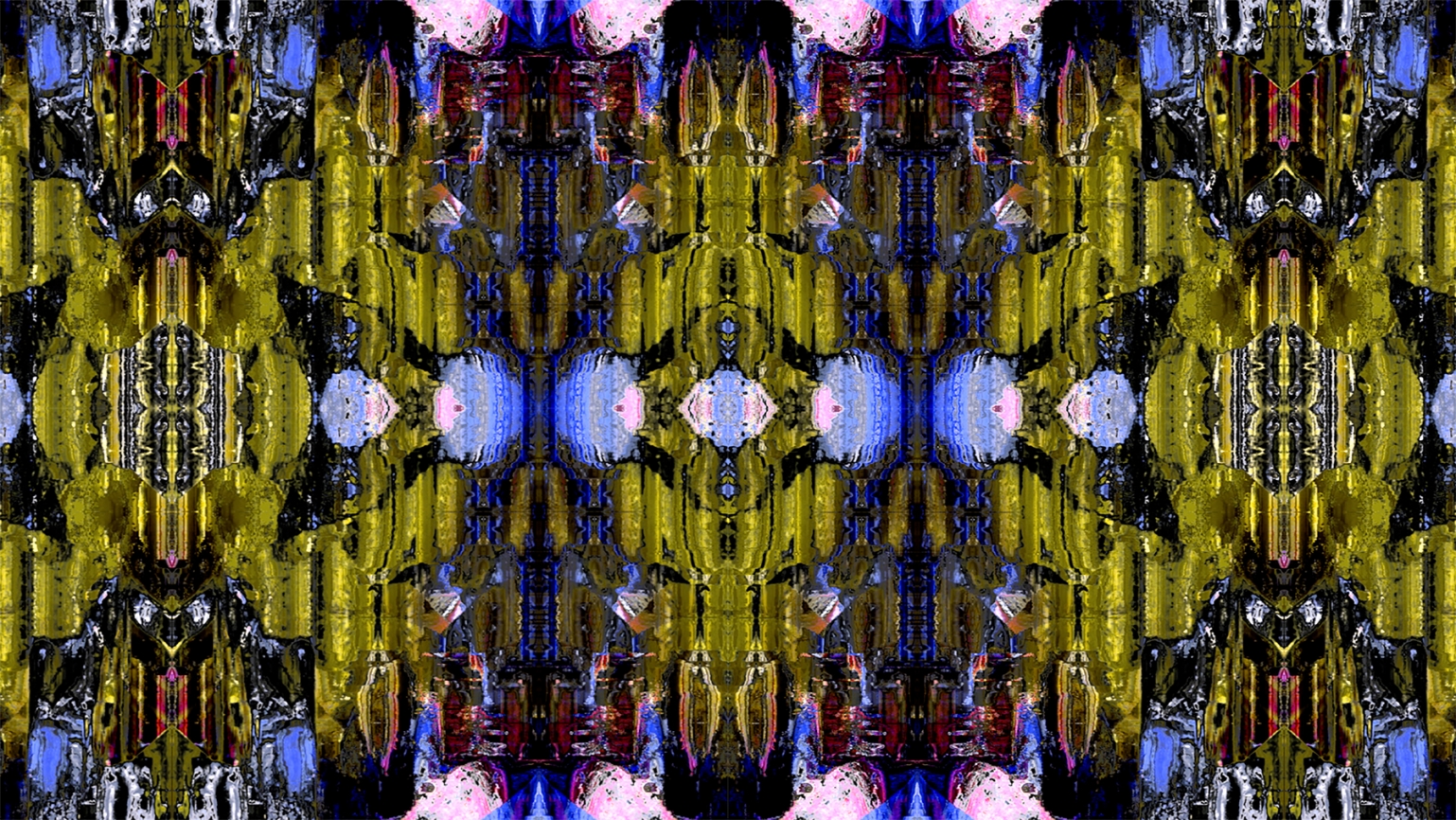

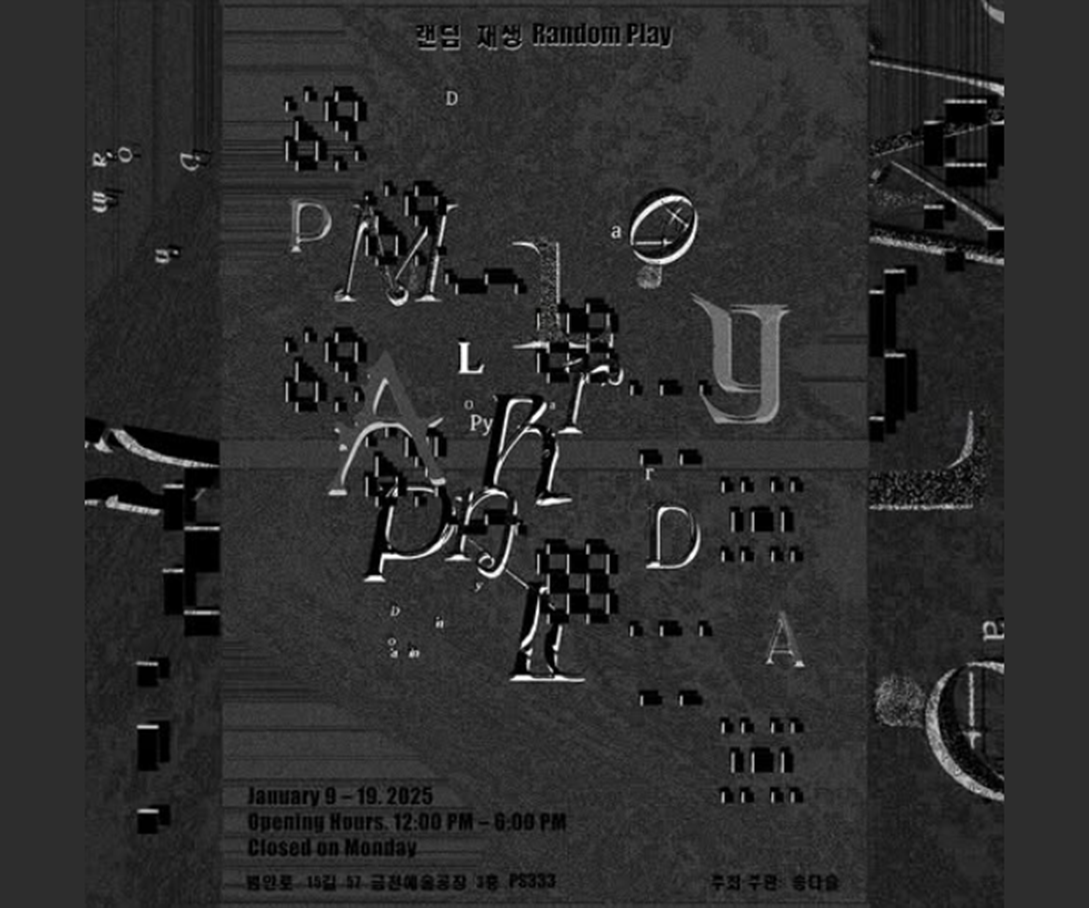

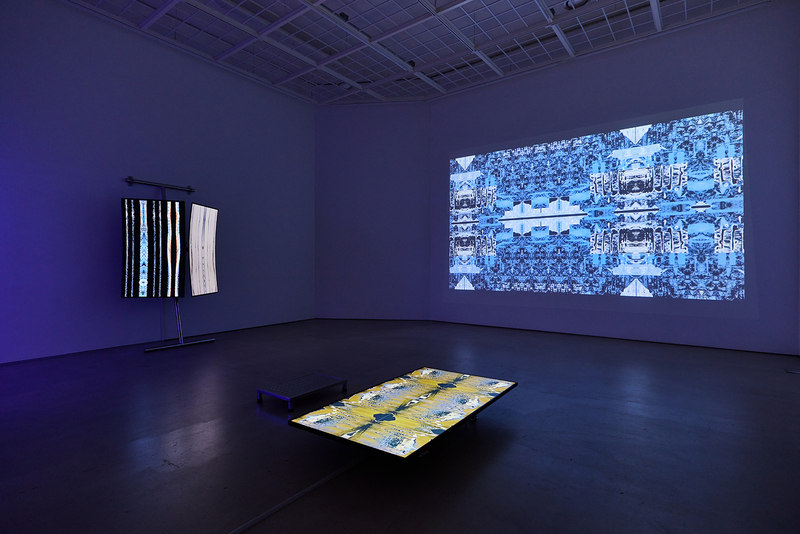

Daseul

Song presents images in various forms, including video, wall installations

within exhibition spaces, and lenticular lenses. The images displayed in this

way appear close to a “glitch.” A glitch refers to the visual manifestation on

a screen when an error occurs within a system.

Song’s

works, which fail to crystallize into any fixed form and appear broken or

shattered, resemble a screen in which an error has occurred. She creates such

images to cover walls or produces videos in which simple waveforms are

endlessly repeated.

In

a past exhibition, Song compared her work to Penelope’s weaving. In Greek

mythology, Odysseus left his homeland to fight in the Trojan War and wandered

the world for nearly twenty years. During this time, his wife Penelope, left

behind at home, was besieged by countless suitors. Penelope refused their

proposals, claiming that she could not remarry until she had completed a burial

shroud for her father-in-law; during the day she wove the cloth, and at night

she unraveled the threads, endlessly delaying its completion.

Here,

Penelope is not a subject who completes something, but a subject who fails.

Like Penelope, Daseul Song also seems to wish for something to fail and be

endlessly deferred along with her work. She places the audience within a

darkness temporarily installed inside the museum and invites them to look at

her work. In conventional video, some form or narrative usually appears. In

Song’s work, however, there is no form and no story, and the audience can only

be exposed to images that appear shattered. These works, in which what is

absent outweighs what is present, are glitches that seek to break away from the

logic of endlessly rising entropy and instead produce negentropy.

The

British film magazine Sight and Sound publishes a survey of

the greatest films of all time every ten years. In the list announced in

2022, Chantal Akerman’s 1975 film Jeanne Dielman, long

notorious for its length and tedium, took first place,

surpassing Citizen

Kane and Vertigo, which had previously

held the top position, and became a major topic of discussion.

As the news

spread, a past remark by Akerman drew renewed attention on social media: “I

steal two hours from someone’s life.” Whenever I encounter videos that bore

me—moments that make me feel the passage of time itself—I reflexively recall

those words. Song’s works have no running time to speak of, and for that

reason, one can continue looking at them endlessly. Rather than doing

something, one does nothing, and in this way, all of life’s time can be taken

away.