The

constraints of the system called the “contemporary,” which constantly demands

renewal, are also applied to art, driving repeated transformations through

frameworks such as expansion, deconstruction, recontextualization, and

post-genre practices. Texts seemingly trapped within fixed “wordings” such as

“new generation,” “post-sculpture/painting,” or “aspects of contemporary art”

often resemble trend reports in fashion magazines or the entertainment

industry’s incessant introductions of newly debuted idols.

Within this climate,

where a generation has become accustomed to presenting itself as a kind of

multi-player—either by choice or necessity—Kwon Osang and Haneyl Choi do not

hesitate to introduce themselves as “sculptors,” and through their respective methodologies,

they explore new trajectories for sculpture as a medium.

Since

the moment when concerns about the expansion of sculpture and the meaning of

“sculpture” itself began to grow somewhat ambiguous,¹ the fate of sculpture has

been continuously swayed. Today, the term “installation” is used

frequently—sometimes indiscriminately—provoking renewed debates about the norms

of traditional sculpture.

Even artists who work through sculpture are divided

between those who introduce themselves as sculptors and those who do not,

making one’s attitude toward self-positioning increasingly significant.

Moreover, perspectives on sculpture have migrated into flat screens, extending

discussions to sculpture within virtual reality. At a time when sensitivity to

the boundary between online and offline has dulled, experiences of sculpture

encountered in immaterial worlds must also be reconsidered.

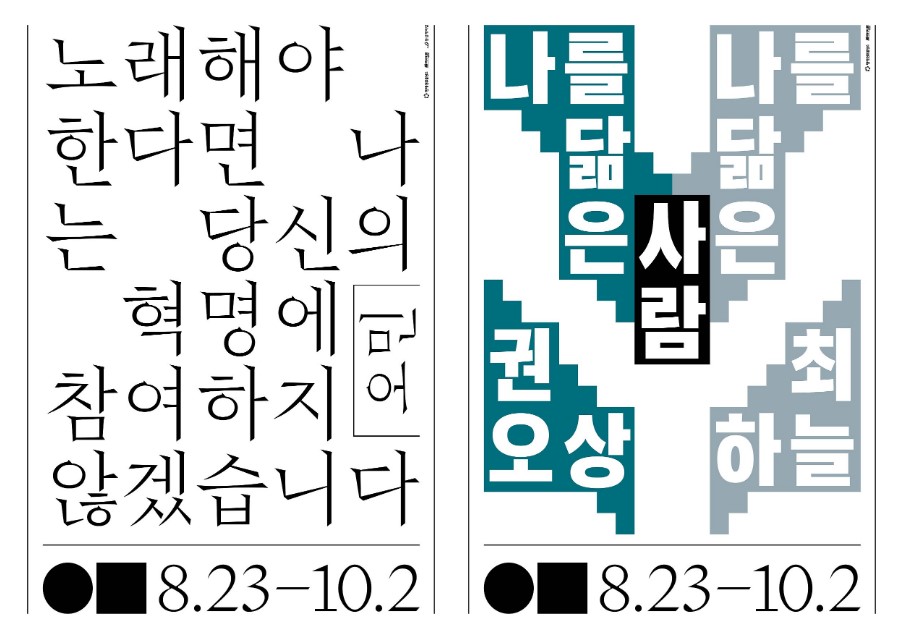

《The Other Self》 likewise examines the

identity of sculpture within the foundation of contemporary art, where

fundamental debates surrounding the medium have accumulated. While Kwon Osang

rejects conventional sculptural methodologies and adopts everyday elements and

materials as his own sculptural language, Haneyl Choi leads new currents in

contemporary sculpture through the reference and reactivation of tradition. By

sharing the exhibition space, the two artists present sculptures as outcomes

(or processes) born of mutual exchange and reference between their

long-developed methodologies, revealing a medium-specific reflection on the

origins of sculpture.

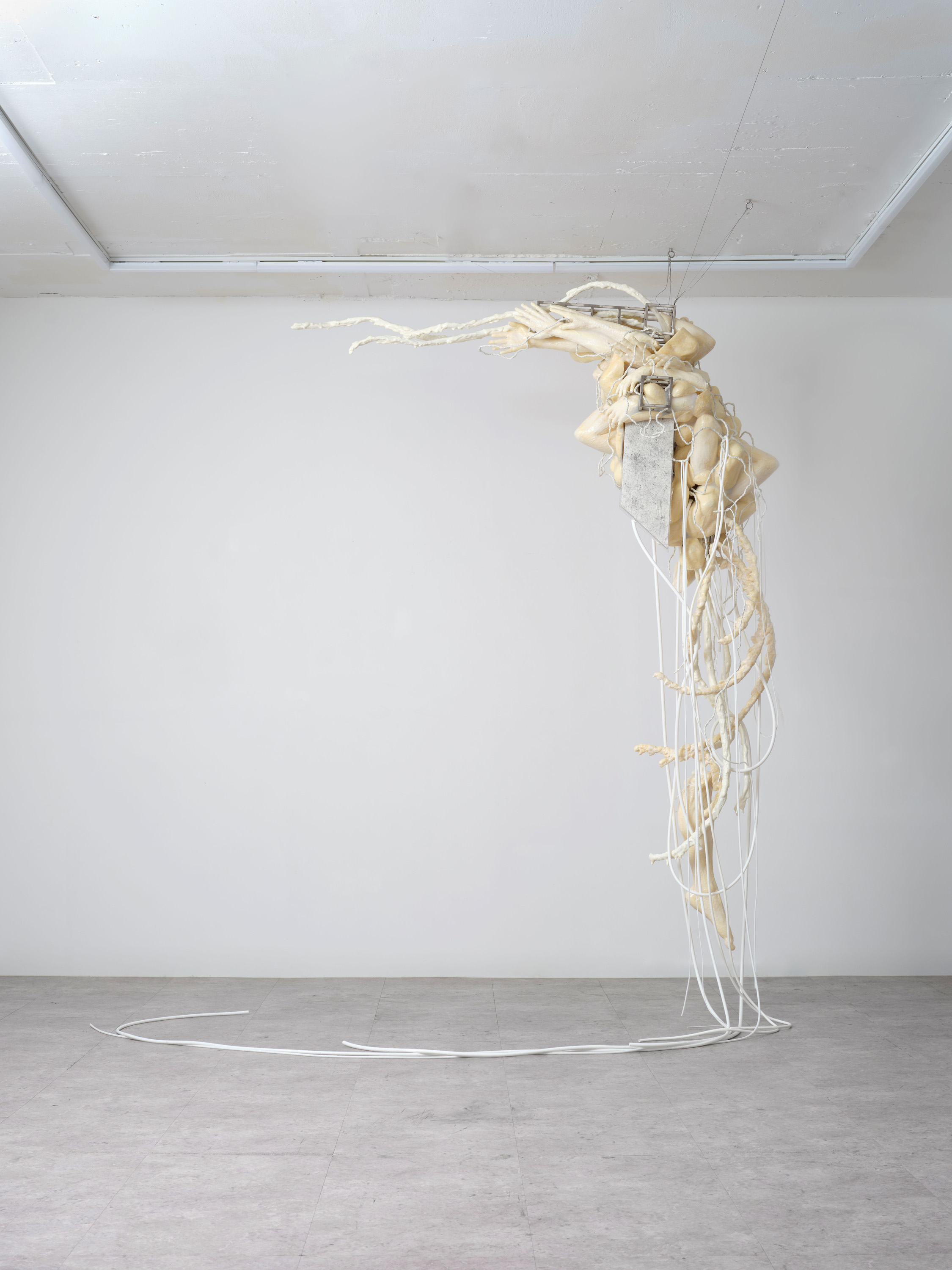

In

this exhibition, Kwon Osang adopts Haneyl Choi’s sculptures as supports,

reapproaching traditionally defined sculptural concepts from a new angle.

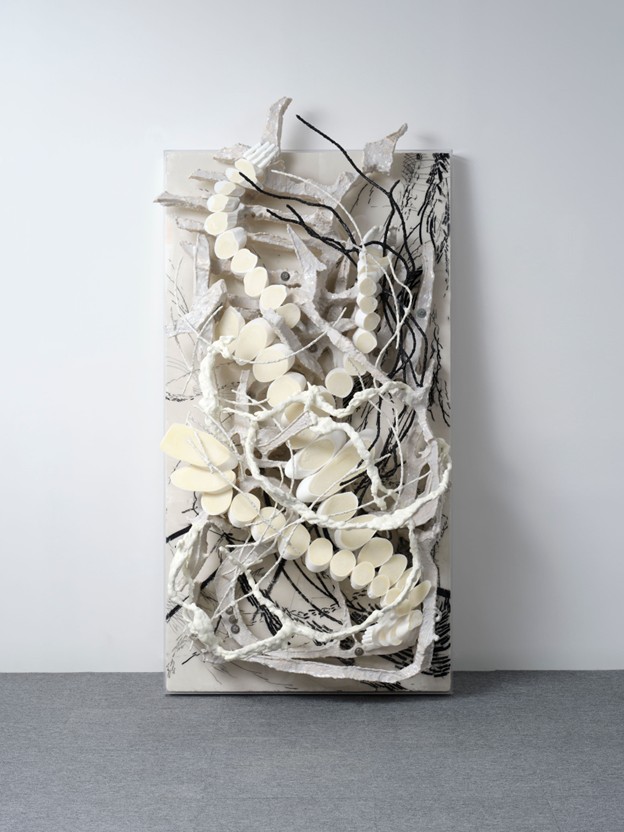

Haneyl Choi, in turn, places side by side 3D-printed works produced through

reference to Kwon Osang’s practice, while also exploring the material

properties of hollow, surface-only sculptures found in Kwon’s early ‘Deodorant

Type’ works.

Additionally, by attaching QR codes—the language of machines—to

sculptural surfaces perceived three-dimensionally by the human eye, and

mediating the experience through a separate object (the smartphone), Choi

invites viewers to encounter sculpture via mobile scanning, thereby probing

sculpture’s material domain through immaterial forms.

In

an era overflowing with new materials and technologies in response to shifting

demands and currents, artists are constantly required to engage in different

forms of assemblage. In this exhibition, Kwon Osang and Haneyl Choi deeply

investigate and exchange each other’s artistic worlds, encountering a demand to

assemble sculpture at the boundary between material and immaterial.

Their

media-based reflections—assembled in the exhibition space—resemble movements of

assemblage that resist being bound: they assemble at opportune moments, then

disassemble and scatter. Although both “assemblage” (結合) and “binding” (結縛) refer to states in

which separate entities, objects, or relationships are joined through certain

factors, their underlying logics differ fundamentally. Assemblage implies a

temporary union that presupposes the possibility of disassembly, whereas binding

denotes a state of stasis in which subjectivity is lost and escape is

impossible.

For

heavy sculptural bodies, binding is often inevitable. In this sense, the shared

remarks made by both artists in interviews² regarding the weight of sculpture

and the harmful material properties that affect sculptors’ health—and their

resulting search for lighter materials—are noteworthy. Through their pursuit of

lightness, the artists’ works are no longer “fixed” within the exhibition space

but instead appear as “placed.”

The use of lightweight materials that abandon

heavy bodies, hollow sculptural forms derived from each artist’s stance toward

art history, and the mobile scanning method that envelops the exhibition space

within an immaterial environment to generate new sculptural experiences—these

are the methodologies of Kwon Osang and Haneyl Choi. This essay examines their

infinitely light sculptural “-ic”³ movements through three interrelated flows.

Even

when sculpture possesses physically light properties, an assemblage devoid of

any perceptible movement ultimately becomes bound. In this regard, Kwon Osang’s

The Three Shades–Wrinkles(2022) and Haneyl Choi’s Old?(2022)

evade binding by operating through their own sculptural “-ic” movements within

the exhibition. In 〈The Three

Shades〉, Kwon employs flat photographic images, yet the

wrinkles of sphynx cat skin render the photographs as undulating images,

producing an optical illusion of surface depth.

Haneyl Choi’s Old?,

which bears a formal resemblance to The Three Shades,

appears as a heavily weighted sculpture due to its corroded iron-like texture,

but is in fact a lightweight work made from 3D printing or Styrofoam. While

Kwon generates illusion through the volumetric effect of flat images rather

than sculpture’s inherent three-dimensionality, Choi disrupts the viewer’s

perceptual cognition through sculptural techniques that induce misrecognition

of material properties.

The

relationship between Kwon Osang’s Meaningless Emission

(2022), leaning against Haneyl Choi’s Become a kenta(2022),

also merits attention. Become a kent takes as its motif the

centaur of Greco-Roman mythology, a creature with a human upper body and a

horse’s lower body. Drawing from art history as reference, Choi reworks this

long-standing cultural and art-historical figure—frequently addressed over centuries

in cultural history, humanities, and popular culture—into a sculpture completed

in just four hours.

Casually leaning against this work is Kwon Osang’s Meaningless

Emission, a photo-sculpture shaped like a standardized trash bag,

installed as if actually discarded, using Choi’s work as a makeshift pole. The

installation of these two works resonates with the intersection of Kwon’s

attempt to dismantle traditional sculptural norms and Choi’s sculptural “-ic”

movement grounded in art-historical reinterpretation.

Haneyl

Choi’s Always reboot: Ghost (2022; reprinted), suspended in

the gallery and directing viewers toward Instagram filters through QR codes

affixed to its uneven surface, along with the unfamiliar codes encountered when

scanning QR codes stamped onto folding screen-like forms that resist easy

categorization as either flat or volumetric, entice viewers to raise their

smartphones and scan.

The presence of QR codes in the exhibition space can be

interpreted not merely as a natural linkage between online and offline prompted

by the pandemic, but rather as a manifestation of an intensified desire to bind

online and offline realms more tightly than ever before.⁴ Before viewers can

even reach a stage of contemplation or judgment, the exhibition space is

incessantly converted into image data and rapidly consumed via social media.

Rather than resisting this trend, the artist actively incorporates it,

unhesitatingly embracing the status of “instagrammable” objects and signs. In

this process, Kwon Osang’s sculptures are also absorbed into the immaterial

smartphone-user environment invited by Haneyl Choi, acquiring new bodies within

virtual space.

While

Haneyl Choi’s SNS-based sculptures allow his works to be summoned outside the

exhibition space, paradoxically, the sculptural “-ic” movement of these works

can only be fully experienced when the codes attempt an immaterial assemblage

that envelops the physically present sculptures during the exhibition period.

Assemblage is completed when viewers physically sense that Kwon Osang’s and

Haneyl Choi’s sculptures have shed their heavy bodies and become infinitely

light, and when the experience of weight is transferred into the virtual realm.

As echoed in Haneyl Choi’s question—“Will sculpture in the future gradually

abandon its body and become lighter?”⁵—only by relinquishing heavy mass

and becoming endlessly light can binding be blocked. Their sculptural “-ic” movements will continue to grow lighter, and they will not be

bound.

1.

Rosalind Krauss argued that from 1968 through the 1970s, many artists felt a

simultaneous permission (or pressure) to conceive of an expanded field, at

which point the meaning of “sculpture” began to grow ambiguous. Rosalind

Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” in Issues in Postmodern Art,

trans. Seungmin Yoo (Seoul: Noonbit, 2017), 158.

2.

Ilmin Museum of Art, “Kwon Osang × Ilmin Museum of Art – What’s my

collection?”, August 26, 2022, https://youtu.be/MSpI6jxewkM; Ilmin Museum of Art, “Haneyl Choi × Ilmin Museum of Art – What’s

my IDOL?”, September 8, 2022, https://youtu.be/Wv9C4AjeZuI.

3.

The dependent noun “-ic” is attached to “sculpture” to emphasize that their

movements are ongoing. Accordingly, this essay refers to their attitudes toward

the medium as sculptural “-ic.”

4.

Cultural studies scholar Sangmin Kim has noted that the active intervention of

QR codes in exhibition spaces prompts reflection (or compels reflection) on

binary boundaries such as reality/virtuality and offline/online. He argues that

offline exhibitions ultimately risk being perceived as limited experiences if

they fail to expand into online connectivity (searching, sharing, saving,

etc.). Sangmin Kim, “Art Experience in the Age of Non-Human Visuality,”

in Curating the Pandemic: Art Experience in the Age of Non-Place and

Immateriality (Movingbook, 2021), 89.

5.

Haneyl Choi, interview with Moonjung Lee, “[The Gallery by Critic Moonjung Lee

(90) ‘Sculptural Impulse’] Will Sculpture Remain Three-Dimensional in the

Metaverse Era?”, Cultural Economy, June 29, 2022, https://m.weekly.cnbnews.com/m/m_article.html?no=143997.