To

put it boldly, everything is “sculpture.” If sculpture is defined as a mass

possessing form and materiality within three-dimensional space, then not only

various artistic genres—such as painting, photography, film, and

performance—but even everyday objects can (with some exaggeration) be

considered “sculpture.” Art critic Rosalind Krauss famously described this

expanded nature of sculpture by stating that the term/genre of sculpture has

been “pulled and stretched.”²

Nevertheless,

what, then, is “sculpture”? Perhaps the question we must pose regarding this

pulled and stretched sculpture is not simply “What is sculpture?” but rather

one that focuses more on the ambiguous “expandability” of sculpture itself. In

other words, beyond the notion of a “mass,” should we not consider continuous

“expansion” itself as one of sculpture’s core values? By analyzing how the

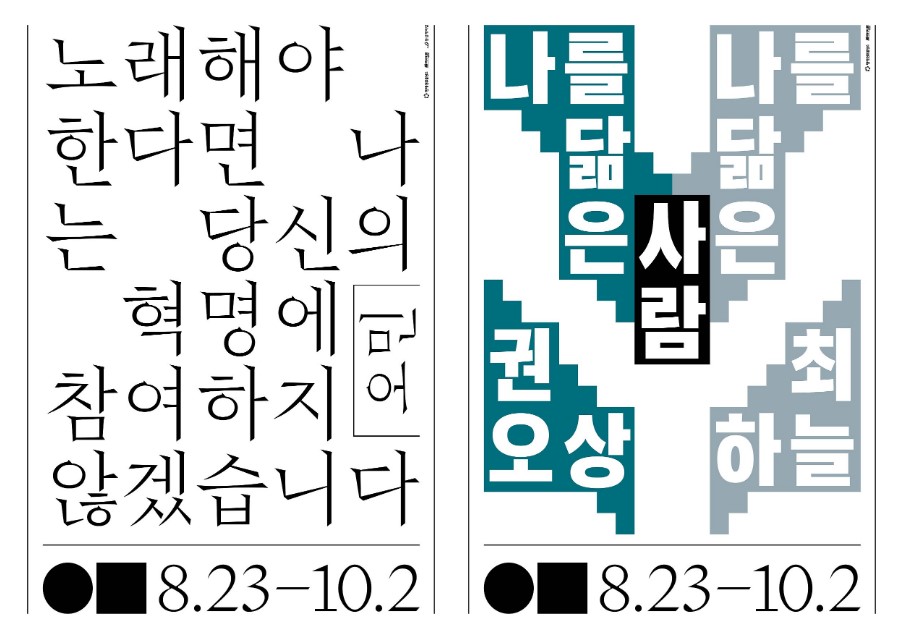

infinitely expanding sculptural worlds of two sculptors intersect and diverge

in the two-person exhibition 《The Other Self》 by Kwon Osang and Haneyl Choi, held at the Ilmin Museum of Art,

this essay seeks to reflect on the elusive and challenging term/genre of

“sculpture.”

“The

Unbearable Heaviness,” which is also the title of Kwon Osang’s 1998 work, is

one of the key terms through which one can enter the expanding sculptural

worlds of both Kwon Osang and Haneyl Choi.³ Located in the lobby of the Ilmin

Museum of Art, Kwon Osang’s New Structure(2022) is part of

his ‘New Structure’ series. Geometric forms and everyday objects resembling

campfires are UV-printed onto flat birch plywood panels and propped upright on

the floor.

The ‘New Structure’ series is an extension and transformation of

‘The Flat’ series, in which advertisement images of watches, cosmetics, and

jewelry from magazines are printed, stood upright to create a kind of

still-life sculpture, and then returned once again to the flat surface of

photography.⁴ In ‘New Structure,’ flat images are brought directly into

three-dimensional space and utilized as architectural elements.

Influenced

by sculptor Alexander Calder’s ‘stabiles’—monumental sculptures in bronze and

steel that replaced the movement of mobiles in the 1930s–40s with curves—Kwon

Osang’s ‘New Structure’ series sheds weight while harmonizing heterogeneous

elements and objects with the surrounding scenery, thereby constructing a new

environment.⁵

The New Structure panel located at the exhibition entrance is a thin wall

punctured with abstract patterns, made from the leftover birch plywood after

cutting out components of the 2022 ‘New Structure’ works shown at Ilmin. By

presenting not only lightness but also void itself as sculpture, Kwon Osang

transforms the exhibition views framed through these holes—each shifting with

the viewer’s position—into possibilities for new environments and new

dialogues.

Although

it is the largest work in the exhibition, Haneyl Choi’s Become a kenta(2022)

is likewise light. This abstract black sculpture evokes both the Japanese

word ‘kenta’, meaning large and healthy, and the Centaur (Centaurus) of

Greco-Roman mythology, known for its powerful body combining a human upper half

and a horse’s lower half. The work was created by the artist tearing away

chunks by hand from a rectangular block of sponge.

Firm yet soft, the sculpture

gathers together remnants of the sponge’s original right-angled form and the

traces of what has been torn away to create a new figure. While both the

material and the method of carving converge on “lightness,” the artist’s labor,

action, and performance embedded in the making process, along with the rough

yet soft surface and subtle sheen of the material, produce “material traces”

that are anything but light.⁶ To borrow art historian Amelia Jones’s eloquent phrasing, these “material traces,” which evoke a sense of “having been made” through the coupling of action

and materiality, “continue

to affect the viewer’s

body and senses, provoking a desire to respond,” and offer a powerful experience.⁷

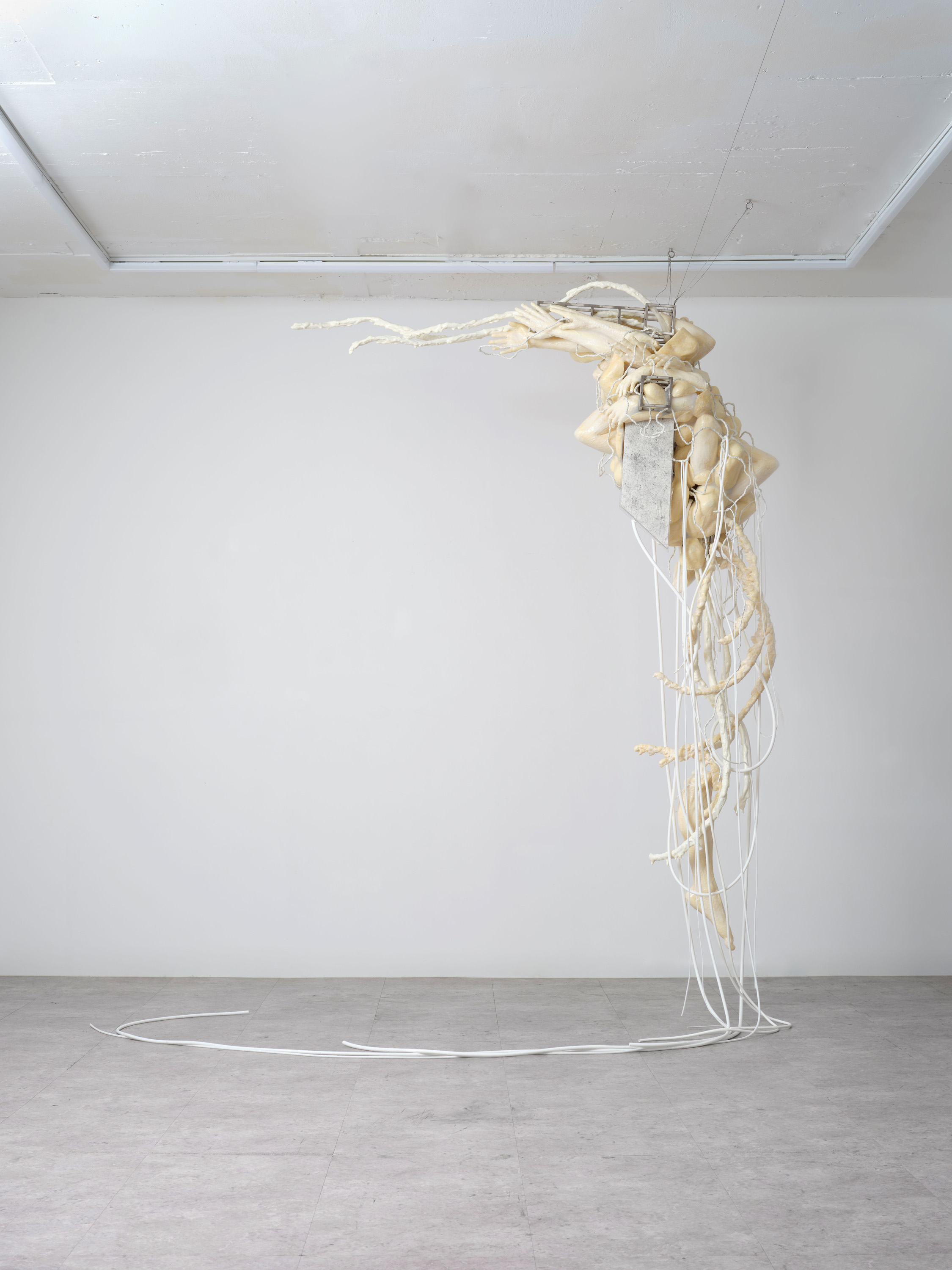

Suspended

from the ceiling at the far end of the gallery, Haneyl Choi’s Booger(2022)

more aggressively strips away the “unbearable heaviness.” This abstract

sculpture—one yet whole, and whole yet one—retains the bumpy skin of Styrofoam

coated in dark gray urethane paint and slowly moves in the air, casting

multiple shadows. It produces both sensory engagement and tension, while its

playful title translates to “the protagonist’s booger.” When viewers scan a QR

code, augmented reality technology fills the gallery with countless nasal

secretions. The sculpture that can be physically touched remains one and whole

until the QR code is scanned; afterward, it multiplies alongside numerous

immaterial sculptures, becoming one within the whole.

The

“expandability” evident in the sculptures of both artists can be connected to

recent discussions on “material agency.”⁸ While Kwon Osang’s sculptural practice, developed

alongside photography, has brought thinness, flatness, and even void into the

realm of sculpture, Haneyl Choi presents tearing as a sculptural method and

immateriality as a sculptural condition through “agents”

such as sponge, Styrofoam, and smartphone applications.

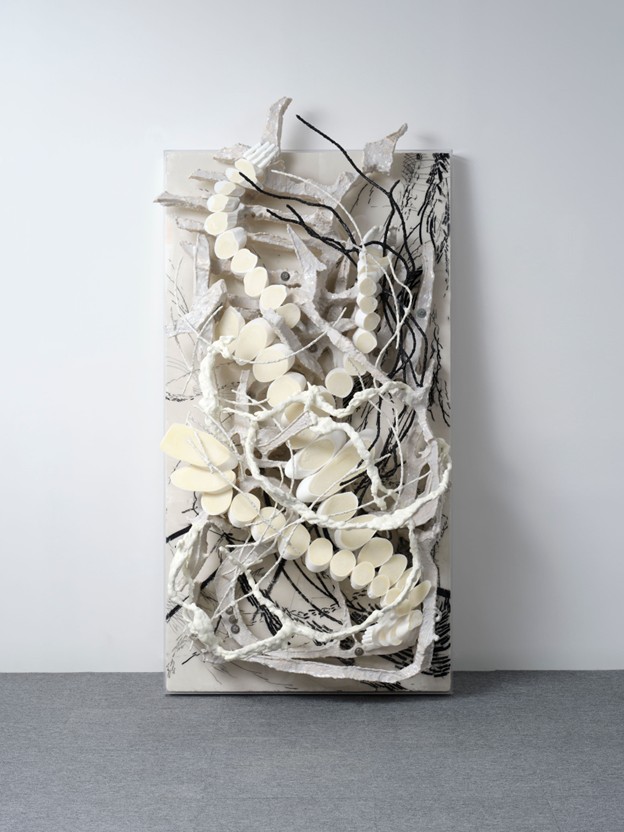

Another

abstract sculpture by Haneyl Choi that strongly asserts physical sensation, Always

reboot: Ghost(2022; reprinted), was 3D-printed and coated in white

urethane paint. Installed as if leaning against the wall in the shape of a

folding window frame, the sculpture is accompanied by a QR code. When scanned,

another similarly shaped but darker abstract sculpture appears in the

exhibition space through augmented reality.

As

its title suggests, this sculpture is constantly being reborn. In 2019 at

Samillo Warehouse Theater, a work titled A T-shirt is the most simple

way to express an opinion appeared as an abstract form holding a

T-shirt and umbrella like a human body. The following year at Ilwoo Space, it

was reborn as Stretch, revealing only a bumpy skin surface.

Earlier this year at the Busan Museum of Contemporary Art, a work with the same

title appeared as a digital form on a screen, resembling an X-ray image or an

undying ghost.⁹

Accumulating the layered histories of sculptures shown across different times

and places—and

destined to be reborn endlessly in new contexts through viewers’ smartphones—this sculpture exists

simultaneously in the past, present, and future, continuously expanding.

This

constant “collecting” or “accumulation” also runs through the sculptural worlds

of both artists. Kwon Osang’s Three Piece Reclining Figure(2022)

is a photo-sculpture composed of thousands of images of Haneyl Choi taken by

Kwon himself. Loosely referencing Henry Moore’s reclining figures inspired by

people sheltering during World War II air raids, the sculpture combines

multifocal and perspective-driven viewpoints to emphasize a muscular body

adorned with tattoos of apples, trees, and fish.¹⁰ The three seemingly disconnected

body-masses are joined atop a pedestal to form a single continuous body—the pedestal itself also being

part of the photo-sculpture.

This

sculpture contains not only a dialogue between Kwon Osang and twentieth-century

sculptor Henry Moore, but also Kwon Osang’s own sculptural history. Having

evolved from hollow photo-sculptures in the 1990s to forms built with Isoping

(reinforced Styrofoam) covered in photographs, Kwon recently introduced another

shift in how the photographic surface is finished.¹¹

Whereas in the 2010s the

surfaces were coated with glossy epoxy to emphasize photographic sheen, more

recent works employ matte epoxy, evoking traditional materials such as wood or

paper.¹² The sculpture shown at Ilmin likewise features a photo-based surface

finished with matte epoxy. Kwon Osang’s sculpture continues to transform from

its interior to its exterior.

Nearby,

Haneyl Choi’s Old?(2022) initially appears to be a smooth

abstract sculpture made from a traditional material—wood—but is in fact a

horizontally placed work created by 3D-printing Styrofoam and coating it with

steel paint. Along with other works in the exhibition, this sculpture initiates

material dialogues among multiple substances. Choi’s sculptures also defy

gravity by floating freely in the air or positioning themselves diagonally,

vertically, or horizontally, constantly seeking new transformations.

At

times, the sculptural histories of the two artists intersect directly. Haneyl

Choi’s Rank(2022), placed at the center of the gallery, is a

3D print created by scanning Kwon Osang’s work. Figures from Kwon’s

photo-sculptures are transformed into data and reemerge as abstract sculptures

in Choi’s style; placed alongside Kwon’s works, they subtly suggest a

sculptural dialogue.

Kwon Osang continues this exchange in The Three

Shades(2022), positioned near the entrance, by using an abstract

sculpture given to him by Choi as a support and covering its surface with

photographs of wrinkled sphynx cat skin. Though differing in surface and pose,

its form closely resembles Choi’s Old?.

Through

these exchanges—moving between figuration and abstraction, emitting diverse

material and immaterial textures, and invoking personal and historical

references—the two artists weave a network of times. Within their light

sculptures, innumerable historical layers accumulate. While they at times

resemble one another through mutual appropriation, their sculptural worlds

continually diverge through individual reinterpretation. The sculptural

dialogue unfolding in the exhibition thus becomes an infinitely branching,

ever-evolving history of sculpture.

One

of the key themes in the Korean art world this year has been sculpture. Amid

numerous exhibitions that spotlight mythical historical figures or simply

enumerate contemporary sculptors, 《The Other Self》 distinguishes itself by

beginning with material and immaterial dialogue between individual sculptors

and expanding this into a sculptural-historical conversation.

Following the

sculptures through the exhibition allows viewers to observe what the two expanding

sculptural worlds share and where they diverge—that is, which spacetimes they

do and do not share. This becomes especially evident in the continuous

“expansion” of sculpture achieved through subtraction and addition by both

artists. In an era when one could claim that everything is sculpture, the exhibition

painstakingly revisits the question of what sculpture is.

1.

The title of this essay is adapted from Jorge Luis Borges’s “The Garden of

Forking Paths” (1941).

2.

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” The Originality of the

Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, London: The MIT Press,

1985), 276.

3.

Kwon Osang, The Unbearable Heaviness(1999), artist

website, https://osang.net/portfolio/1999-underable-heaviness.

4.

“Kwon Osang,” Arario Gallery, https://www.arariogallery.com/ko/artists/119-gwon-osang/.

5.

See note 4.

6.

On material traces, see Amelia Jones, “Material Traces: Performativity,

Artistic ‘Work,’ and New Concepts of Agency,” TDR/The Drama

Review 59, no. 4 (Winter 2015): 18–35, https://doi.org/10.1162/DRAM_a_00494.

7.

Ibid., 20.

8.

A discourse—including theories by Bruno Latour and Jane Bennett—that considers

objects as agents comparable to human subjects, examining how objects influence

human actions to discuss new socio-political structures.

9.

Storage × Haneyl Choi, Stretch) [2019 (reproduced 2022)],

artist website, https://www.choihaneyl.com/mocabusan; Haneyl Choi, Stretch, 2019, artist

website, https://www.choihaneyl.com/ilwoospace; Haneyl Choi, A T-shirt is the most simple way to

express an opinion), 2019, artist website, https://www.choihaneyl.com/.

10.

On the reclining figure series, see “Everyday Objects in the Sculptural

Practice of Kwon Osang,” Naver Design Press, October 15,

2021, https://post.naver.com/viewer/postView.naver?volumeNo=32560031&memberNo=36301288.

11.

On Kwon Osang’s “deodorant-type” sculptures, see “Kwon Osang,” Arario

Gallery, https://www.arariogallery.com/ko/artists/119-gwon-osang/biography/.

12.

On the matte surfaces of Kwon Osang’s sculptures, see “[Critic Lee Moon-jung’s

The Gallery (75): Sculptor Kwon Osang’s ‘Sequence of Sculpture’] Expanding the

Experimental Nature of Photo Sculpture after COVID-19,” Cultural Economy,

September 14, 2021, https://m.weekly.cnbnews.com/m/m_article.html?no=140204.