Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

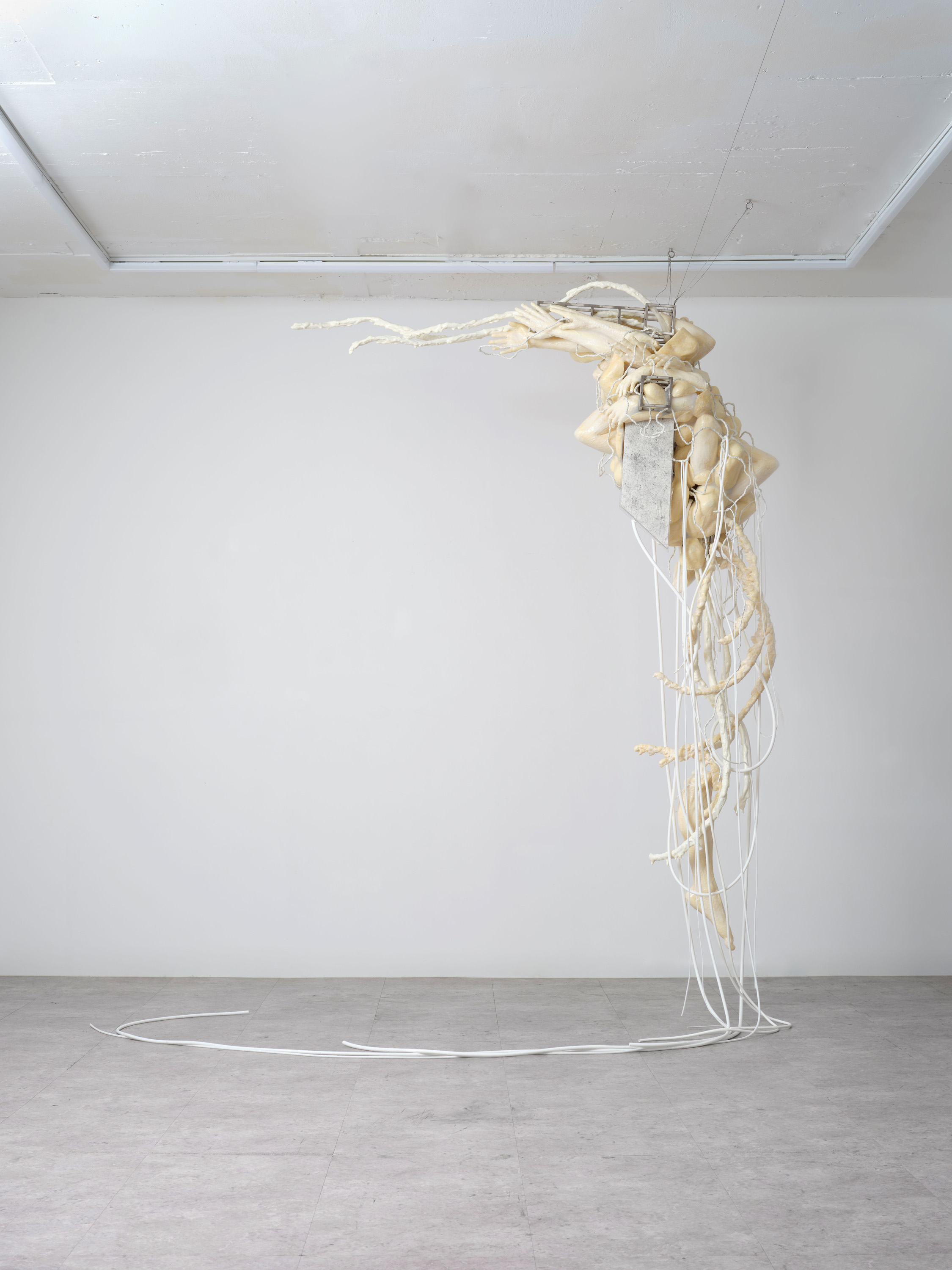

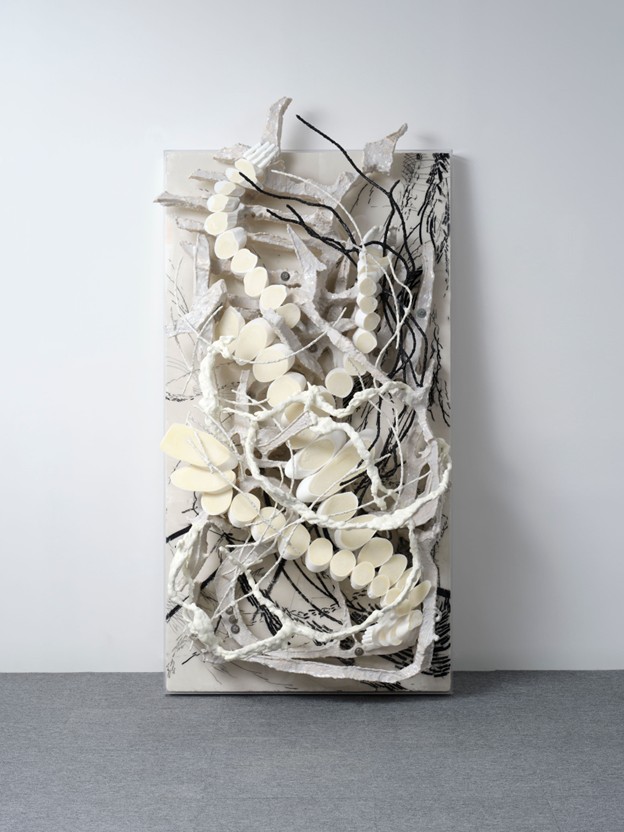

Choi’s solo exhibitions include 《Manner》 (P21 &

Gallery2, Seoul, 2022), 《Bulky》 (ARARIO MUSEUM, Seoul, 2021), 《Siamese》

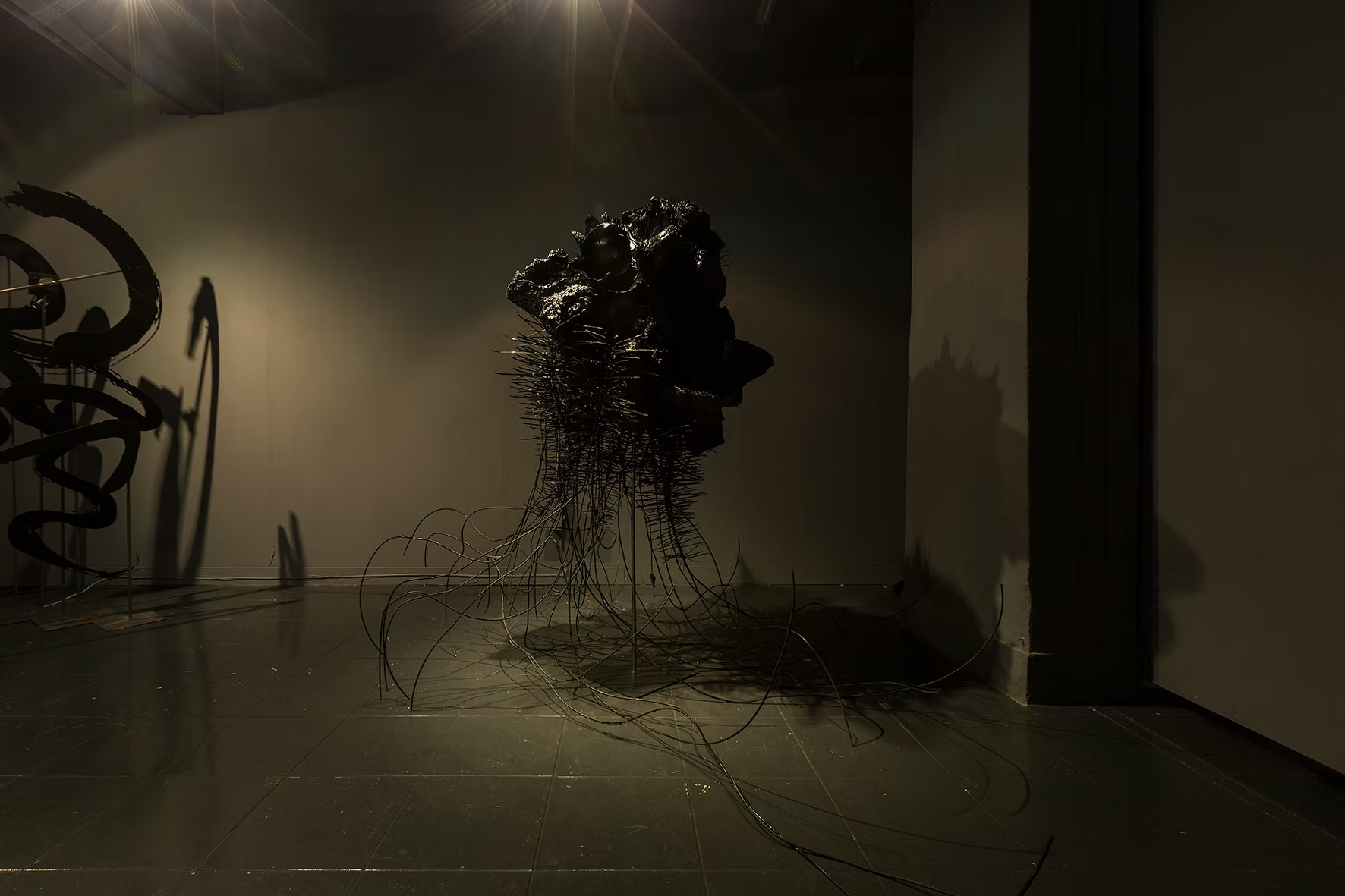

(P21, Seoul, 2020), 《Traitor’s

Patriotism》 (Commonwealth & Council gallery, Los

Angeles, 2018), and more.

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Choi has also participated in numerous group exhibitions,

including 《Pigment Compound》

(P21, Seoul, 2025), 《Aura Within》

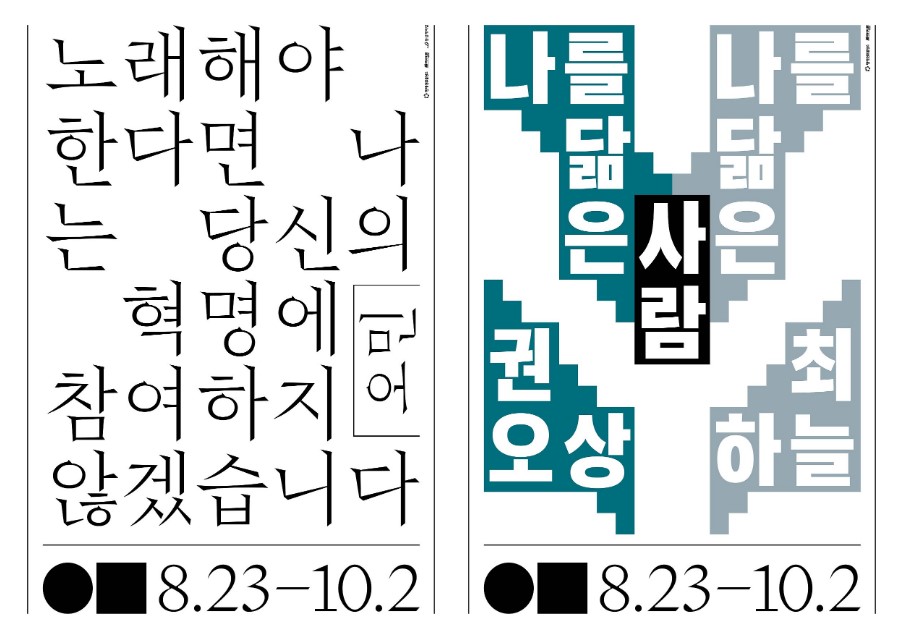

(Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, 2025), the 15th Gwangju

Biennale 《Pansori, a soundscape of the 21st century》

(Gwangju, 2024), 《UNBOXING PROJECT 3:

Maquette》 (New Spring Project, Seoul, 2024), 《DUI JIP KI》 (Esther Schipper, Seoul, Berlin,

2023), 《Fantastic Heart》 (Para-Site,

Hong Kong, 2022), 《The Other Self》 (Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, 2022), and 《Human,

7 questions》 (Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul, 2021).

Residencies

(Selected)

Haneyl Choi participated as an artist-in-residence at the SeMA Nanji

Residency (2021) and the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture’s Seoul Art

Space Geumcheon (2019).

Collections

(Selected)

Choi’s works are held in the collections of

the High Museum of Art, Atlanta; the Sunpride Foundation, Hong Kong; the

Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami; and the Daegu Art Museum.