Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Chang

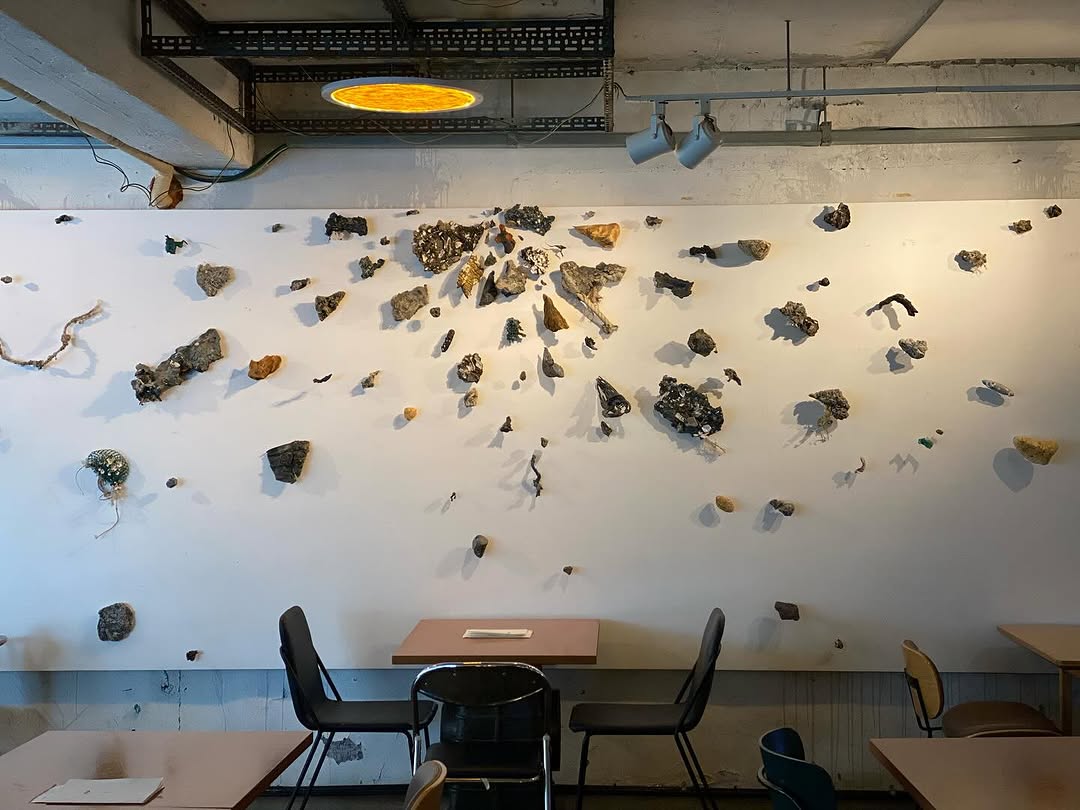

has held solo exhibitions including 《Neo-Nature,

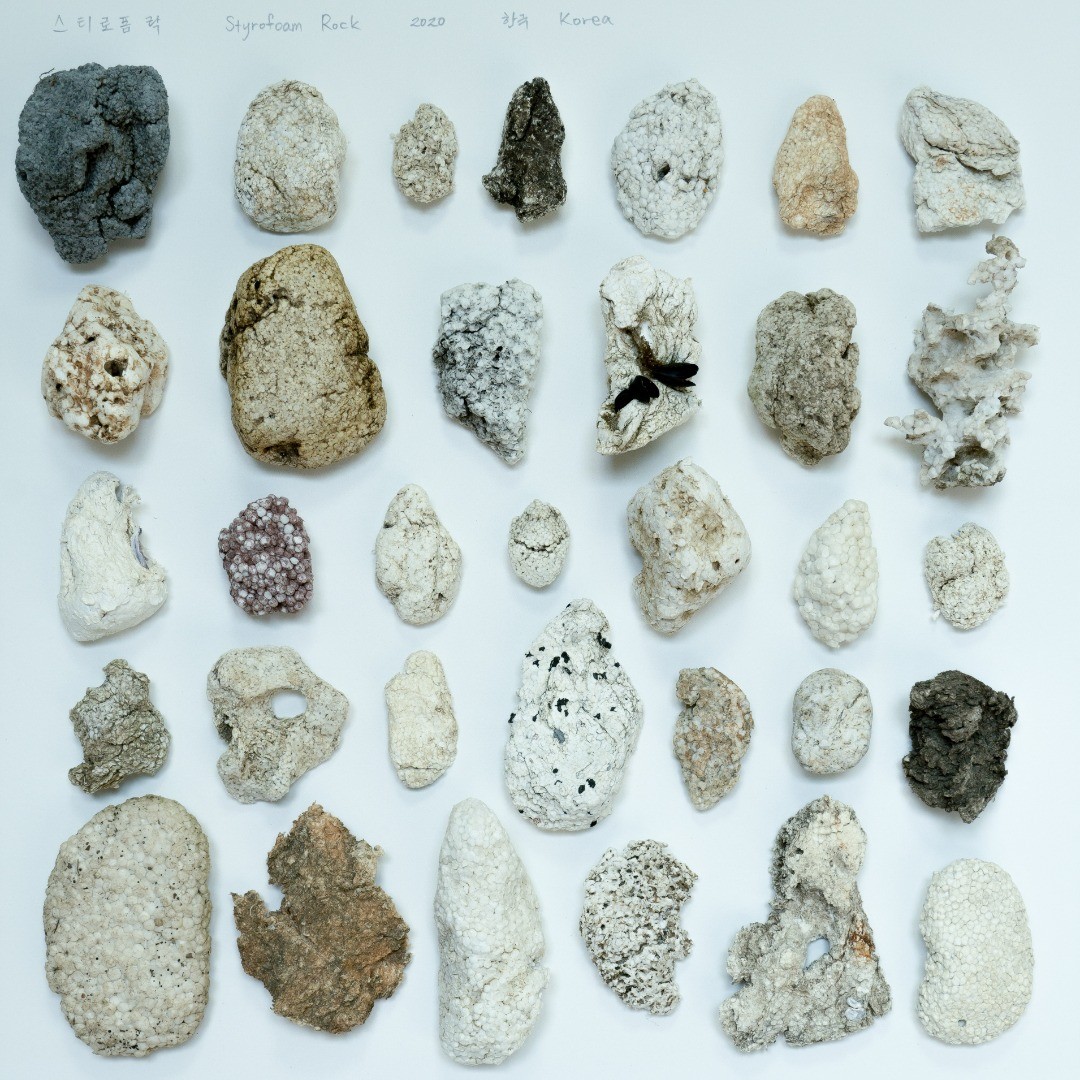

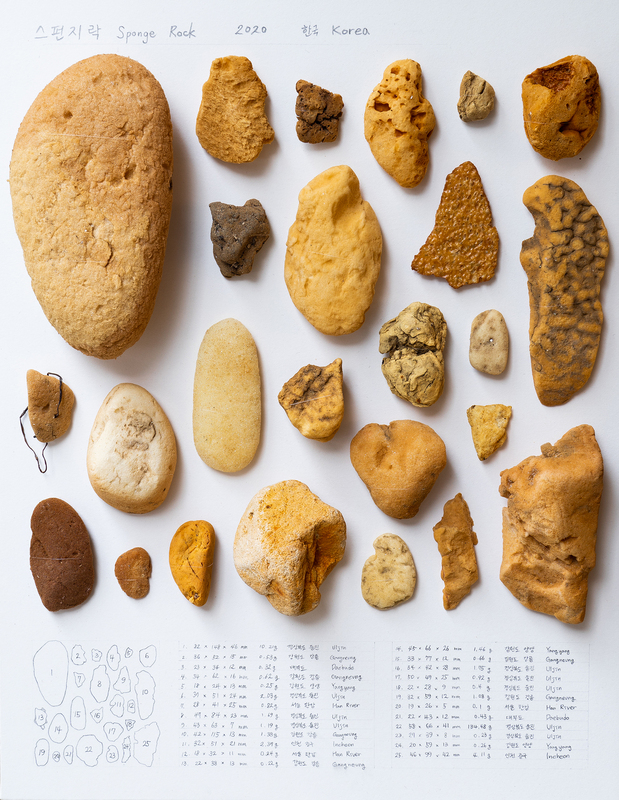

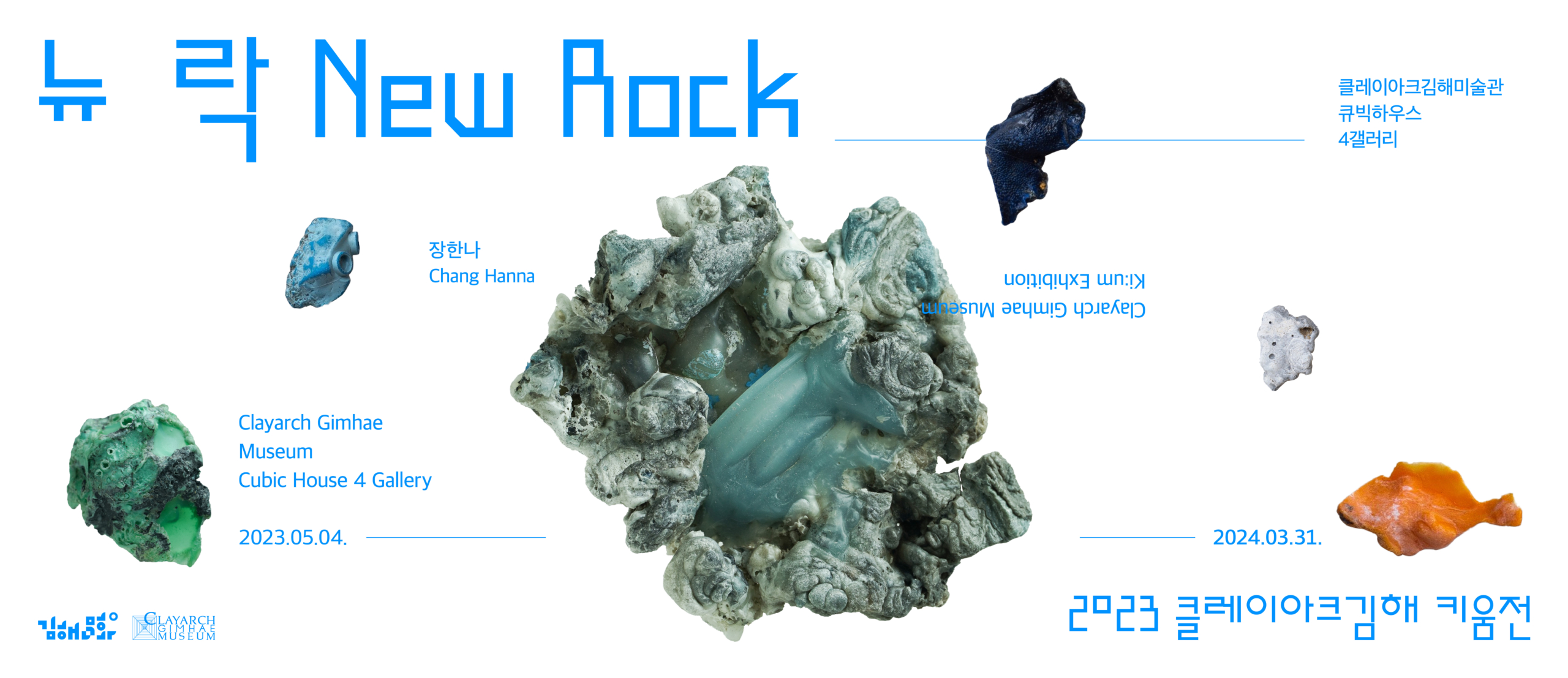

Neo-Land Art》 (Chilsung Shipyard, Sokcho, 2024), 《New Rock》 (Clayarch Gimhae Museum, Gimhae,

2023), 《The Birth of New Nature》 (Mudaeruk, Seoul, 2023), and 《New Rock》

(Studio Square, Suwon, 2020).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Chang has also participated in numerous group

exhibitions, including 《Earth, Once More: Responding with

a New Sensibility》 (Art Archives Seoul Museum of Art,

Seoul, 2025), 《Random Access Project 4.0》 (Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, 2025), 《Young

Korean Artists 2025: Here and Now》 (MMCA, Gwacheon,

2025), 《Equity: Peaceful Strain》 (Gwangju Biennale Pavilion, Gwangju, 2024), 《Climate in Everyday Life and Strange Climate》 (The National Science Museum, Daejeon, 2022), and more.