Floating

people share a commonality in that they presuppose some purpose and

destination. Yet when we say “floating,” the term does not refer solely to a

carefree life. In cities, on the sea, and inside subway cars, people sometimes

form groups that clearly articulate a shared purpose, while at other times they

form collectives without any specific sense of purpose. Driven by a wide range

of external factors, these individuals are influenced, on a macro level, by

social and political conditions that emerge between nations or between states

and individuals.

On a micro level, their movements are shaped by corporate

restructuring, familial relationships, and academic pursuits. All of these

individuals move toward purposes that are partially similar or different.

Particularly from an individual, micro perspective, it becomes difficult to

judge purpose at the level of the group. Like people waiting together for a

flight at an airport, in situations where means of transportation are widely

shared, individuals may be together without sharing the same destination—the

means alone are common. Likewise, on social network services, followers

appearing on a timeline do not all use the space with the same purpose. Even

when the means are identical, each person’s orientation can differ.

Means

not only homogenize differences without allowing them to surface, but also view

and control everyone as the same. When wielded under the banner of human nature

or universal equality, means acquire a totalitarian character and become ends

in themselves. In pursuing an ideal, macro-level subjects and individual

subjects move—or attempt to move—in different directions. While the former

seeks to construct an overall outline, the latter struggles to escape from

within that outline. Both nonetheless involve someone’s movement—footsteps

taken to reach a purpose and destination.

Yet footsteps function differently

depending on what drives them. Unlike broad categories such as citizens, youth,

or all app downloaders, individuals break away from such frames—sometimes with

clear intentionality. The micro level seeks to open forward against the

totalization and homogenization enacted by the macro level that mixes

everything into one. This series of relationships can be described as

“stirring.” A leader’s uniform stance, the confusion it generates, the

individual gestures mobilized to carry out a purpose, and the collective voices

raised to break through stifling situations—each exerts its own force.

Stirring, as a means, can either produce homogenization or create fissures

within it, depending on what is being stirred.

In

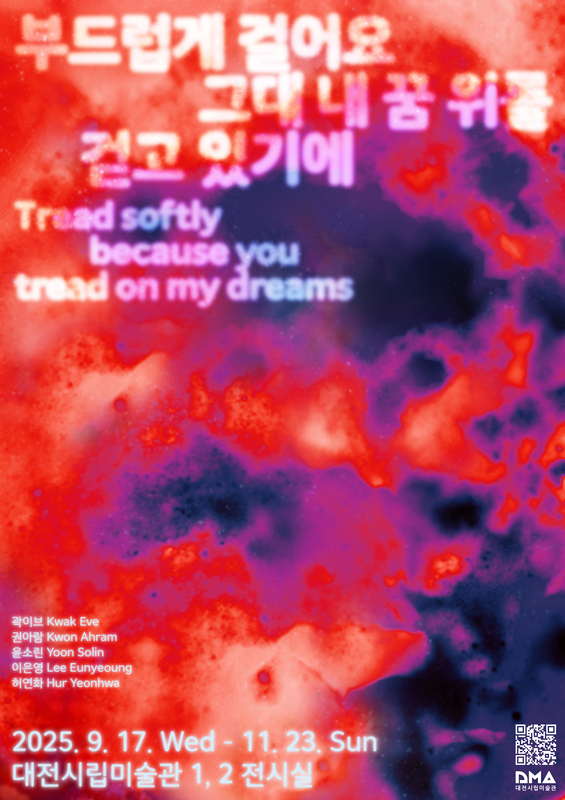

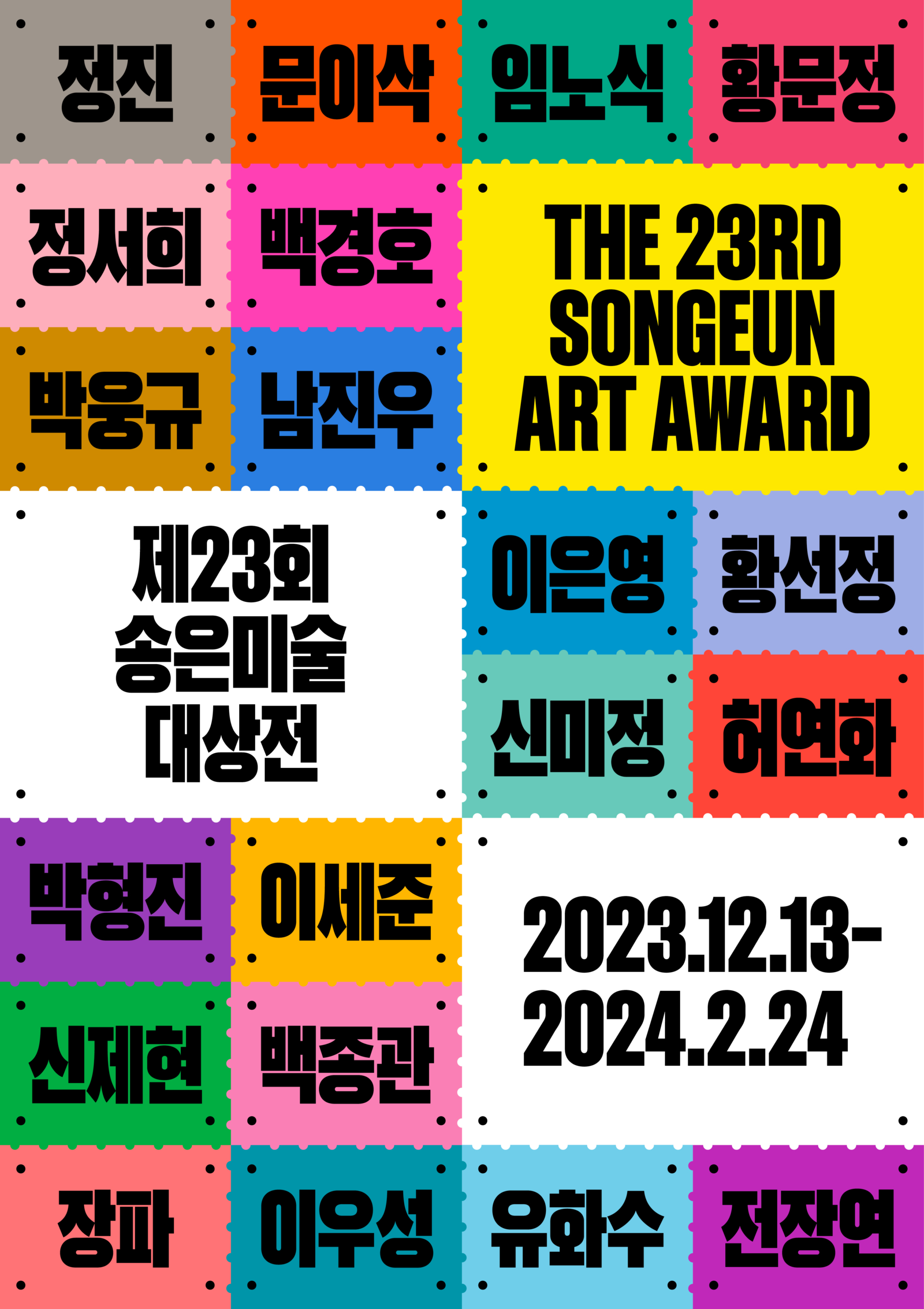

Hur Yeonhwa’s solo exhibition 《Floating People》, viewers encounter a range of media, including edited and printed

images, paintings, clothed canvases, and figurative objects. Though each work

is formally distinct and individual, their placement in multiplicity across

wooden structures and interior/exterior wire fencing causes them to appear

collectively. The exhibition title comes to mind in light of the

permutation-free arrangement of multiple components within a single space.

Meanwhile, phrases such as “variable exchange” or “datafied bodies” allow us to

infer the thematic consciousness embedded in the title.

Exchanges and

relationships that drift and hover inevitably evoke contemporary social

conditions. How, then, is “stirring” emphasized in this exhibition, and how

does it relate to the thematic consciousness implied by the title? Stirring

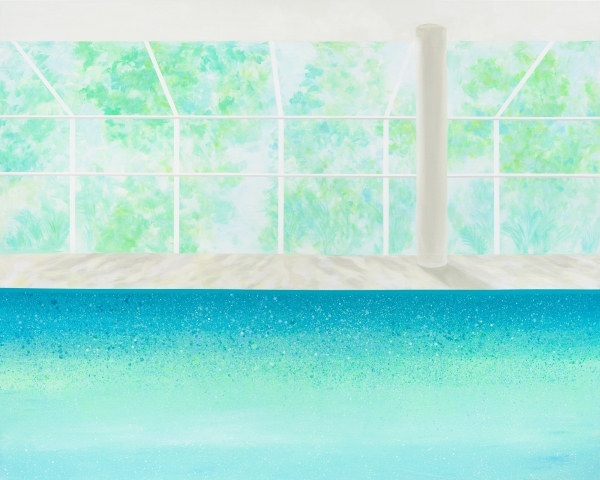

operates on a technical level through abstraction. By editing and merging

multiple images, painting them to appear ambiguous, revealing only parts of

objects through thin or perforated materials, and presenting viscous objects,

stirring is shown through works that mix multiple entities or condense them

into one.

In this exhibition, the dispersive and aggregative effects of

stirring are manifested not only in the collective or individual installation

of works within the space, but also in attempts within the works themselves to

integrate and arrange collective or individual elements. In this sense, the

works create a site in which the targets and elements of “mixed media” and

“medium mixed” are swapped.

However,

abstraction may be perceived negatively, as in criticisms that accuse works of

distortion or of failing to present things straightforwardly. If one adopts

evaluative criteria that prioritize direct representation of reality or

actuality, these works might be reduced to “fiction” in a pejorative sense. In

Hur Yeonhwa’s exhibition, abstraction is neither a distortion of reality nor a

misinterpretation of the real. Rather, abstraction here articulates the bodily

gestures humans perform in reality—namely stirring—and the effects those

gestures generate.

As noted earlier, stirring in itself cannot be declared

either negative or positive. It can erase differences to create sameness, or

become the footsteps of individuals seeking to break through homogenization,

eventually forming collective voices. In this exhibition, abstraction appears

as a field that not only suppresses and excludes but also mixes, unifies, and

allows disparate elements to coexist. Stirring thus captures the ambivalence of

abstraction and resonates with the contemporary dynamics of dispersion and

aggregation that the artist considers.

Stirring

is reflected not only in the thematic aspects of the works but also in their

placement within the exhibition space and in their production methods. Rather

than judging stirring as inherently negative or positive, viewers come to

understand that its value depends on the results produced after something—be it

the state, a particular group, oneself, or society—is stirred. The gesture of

stirring is concentrated in a work consisting of a triangular canvas clothed

and bearing hand-shaped objects.

This piece can be read as depicting a leader

with arms crossed, an oppressed individual, or a figure expressing solidarity,

demonstrating how meaning shifts between binding—oppressively confining an

object—and joining forces. The subjective stance of stirring to bind, and the

footsteps that seek to open and move forward from a bound state, lead to

different destinations depending on what is stirred and whether the movement is

total or detailed. What the artist presents in this exhibition is the

operational logic of stirring: a dynamic relationship that encompasses macro

and micro levels, control and solidarity, and both incorporation toward unity

and deviation that escapes from it.