“Things

fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” (W. B. Yeats, The Second Coming, 1919)

“Who

are we, the unstable ones, and how have our experiences come to be woven so

precariously?” (Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Rhapsody for the Precariat,

2013)

At

a time when physical space no longer functions as it once did, the only

sustainable place available to people is the online realm. In the wake of

COVID-19 and social distancing, humanity connects online to maintain networks

as communities, groups, and crowds. As the velocity of physical space slows,

the speed of online space accelerates in response, and the scale of its systems

expands uncontrollably. Under the influence of the pandemic, the hesitation

that once demarcated plazas and online agoras, the material and the immaterial,

has already disappeared.

As if to testify to this era, slogans and advertising

images across online and offline spaces have also begun to change.

Advertisements for Netflix, app services, games, and online shopping have

proliferated, while the few ads that still point to the physical world tend to

be for new apartment developments and real estate investment. We go to Netflix

to watch films, to YouTube to view exhibitions, and to SNS or Zoom to meet

friends or colleagues. People move, gather, and disperse along the flows of

online networks, laboring, producing commodities, and pursuing profit. In

online space, the flow of users’ thoughts and actions is converted into data

values. But where, then, is our body located in this space? And how does the

body encounter the emotions, objects, and values derived from online space?

Hur

Yeonhwa’s work explores reorganized social systems formed through the

relationship between the physical and the non-physical, the offline and the

online, and the modes of bodily existence shaped by these systems. Given the

artist’s interest in online networked communities—particularly structures of

group purchasing and monetary exchange among people who share tastes and

purposes—it is hardly surprising that blockchain systems and cryptocurrencies

came to mind as she conceived this exhibition. Rather, at this juncture, the

artist becomes aware of the structural contradictions she inhabits within a

world where such systems circulate broadly on social and economic levels, and

she seeks to address them through visual sensation and spatial arrangement.

One

such dissonance arises from the confusion and conflict produced by the fact

that blockchain systems used for cybercrime and P2P systems used for file

sharing are essentially identical. “In a sense, I am also participating in

reinforcing a system,” she notes. “Belonging to such a collective, and the

contradictory state in which values inevitably collide within it, gives me a

feeling of floating even more than before” (from the artist interview). In

systems where information is distributed and shared by participants rather than

centrally managed, where even if one fragment of the whole deviates information

can still be operated by other participants’ fragments, what the artist senses

is that such structures are “similar to human social structures and the process

by which humans form groups” (from the artist interview).

The

paradoxical situations embedded in online environments that appear to be

autonomous networks form the basic structure of the exhibition space. The walls

that constitute the main circulation of the exhibition are not solid supports

but rather combinations of perforated walls riddled with holes and loosely

structured mesh fences. On the wall that visitors encounter upon entering,

three large holes are set into a surface surrounded by a mixture of

images—subways, glass cups, skies, hands holding smartphones. The holes point

to a desire to see, yet the absence of an object leads the gaze toward

subsequent scenes and events.

Here, the holes do not remain as mere blanks or

gaps. Like the structure of a blockchain, they are themselves endlessly

unstable, connected to fragments and becoming passages into the next field of

events. Along the fences that extend beyond the wall into the interior of the

exhibition space and on block structures placed at the center, objects of

various material qualities are arranged. These works, which appear to share

little narrative coherence, contain fragments of the artist’s daily images,

thoughts, and incidents, and emerge without formal boundaries as sculpture,

painting, installation, and printed matter.

What is distinctive is that

fragments derived from a single event intervene in the emergence of other works

afterward, in independent ways. For instance, the blue rose pattern of a

garment the artist favored becomes patterned onto transparent A-stage material,

forming a membrane for a painting, and later reappears as a resonant pattern

with snowflakes in another painting depicting snowfall. Through such processes,

entities that had been separated form relationships retroactively and with a

temporal lag.

This

cyclical structure of time is also evident in the exhibition’s spiral

circulation. While walls guide the viewer, there is no clear distinction

between front and back, and the circulation remains open and fluid, much like

an internet browser. At the center of this configuration, sculptures placed

atop wooden structures possess an excess of corporeality that stands in

contrast to the smooth textures of mapped images. These works partially

reproduce bodily imagery, with distorted or contorted forms composed of

combinations of diverse materials. They share several characteristics centered

on materiality.

First, they evoke parts or organs of the human body. Second,

they possess twisted structures in which exterior and interior, inside and

outside, are inverted. Third, they take on ambiguous forms that resist clear

definition. Fourth, nonetheless, they leave impressions of flesh and skeletal

frameworks entangled together. Generally cast in plaster or Cibatool and then

coated with plastic clay and silicone to add flesh-like textures, some

sculptures forego casting altogether, relying solely on clay and silicone to

develop their surfaces.

This

feast of diverse and delicate textures recalls the artist’s background in

sculpture, yet her mode of sculptural thinking departs from traditional

sculptural attitudes. Consider, for example, the blue three-figure sculpture

placed above. The figures were originally created by the artist as a 3D model

in 2016, later reproduced as a sculptural framework, and then copied again over

time to produce additional sculptures. This work, born through the manual

self-replication of a simulation, evokes—through bodies of clay and silicone

that appear to melt into one another—an uncanny resonance with the tragic

sensibility of nineteenth-century

Romantic sculpture. The dissonance in this

exhibition is paradoxically heightened by the materiality of the hand that recreates

the effects of digital technology. By damaging smooth surfaces, blurring

contours, and resisting the differentiation between surface and form, the

sculpture gradually becomes a mass of sensation in which flesh and bone

intertwine. Alongside this are a range of sculptural works: digital face

sculptures molded in clay, pastel-toned selfie sculptures softened as if by

filters, plaster rib-like forms, and carefully clothed figures.

Within these

works, oppositions and tensions—between materiality and immateriality, flatness

and volume, present and past, classical and contemporary—are absorbed into

sculptural materiality itself. Describing one face-mapped sculpture, the artist

notes, “I worked as if applying a thin image onto a face while mapping it in a program”

(from the artist interview). In her sculptural practice, she assumes her own

body as 3D software and borrows the sensibility of tools, yet ultimately

reinterprets the gap between material and immaterial through the most

oppositional tactile sensations. Her sculptures, which translate a contemporary

sensibility of countless coexisting presents—like a timeline—into bodily

existence, excavate the possibility of material beings that can encompass even

distortions of time.

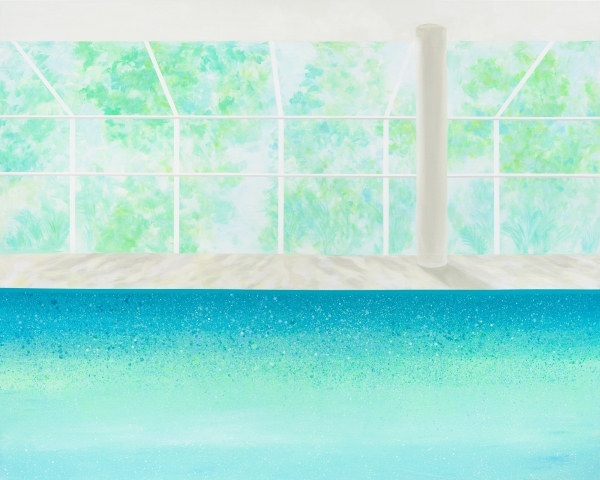

Meanwhile,

on one side of the exhibition space, geometric sculptures folded from printed

mapping data flatten once more the compressed temporal gap produced through the

materialization of sculpture. On the walls, abstract paintings in which images,

dreams, memories, impressions, emotions, and desires intermingle quietly take

their place. Just as viewers begin to sink into the dreamlike and hazy

sensations of sculpture and painting, a ghostly message of commodities calls

for awakening from below.

The phrase “Let your body relax,” taken from an

advertisement video for a sleep-inducing application, is laid across the floor

beneath the structures, like a curtain of the unconscious operating at the

substructure of consciousness. While it appears to encourage calm and support,

the instability of systems that prioritize commodity value and capital

accumulation ultimately jeopardizes the flow and narrative of time

itself—sustainability.

The inevitably fragmentary relationships among

individual works confront self-division and alienation arising from a

perforated system by making retroactive contact through chains of material

interaction. In this way, the artist reassembles, in fragments, portraits of

contemporary individuals floating between incompatible worlds, fully exercising

the gravity of an era that, like an internet banner window generated by

algorithms, is “incapable of becoming serious.”