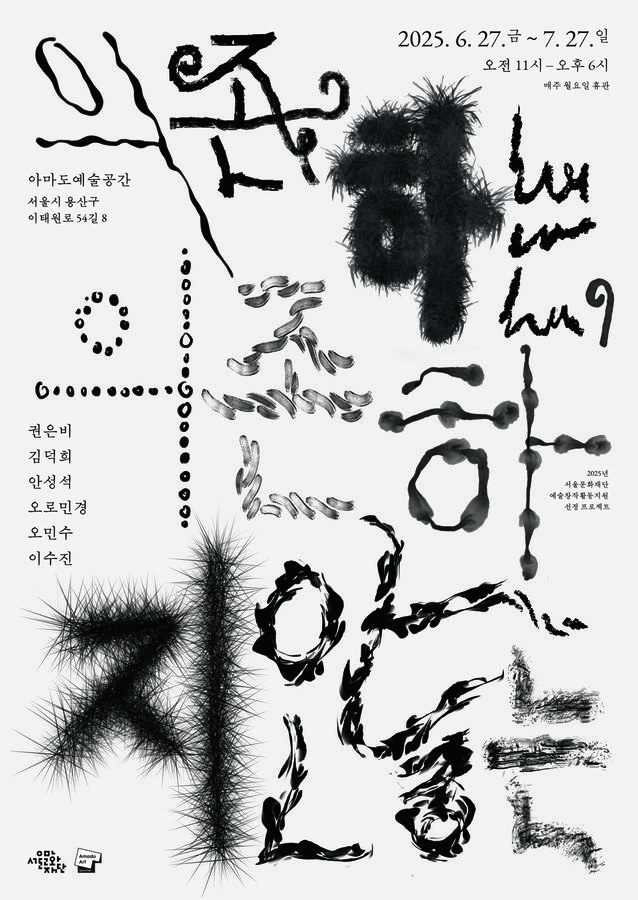

Early

in the research phase, I found great inspiration in Christine Sun Kim’s TED

Talk, “The Enchanting Music of Sign Language.” She describes how

sound, which she once thought irrelevant to her life, is actually close to her

— how American Sign Language, unlike linear spoken language, is spatial and

feels like harmony. Later, watching performances and documentaries, I found

both American and Korean Sign Language to be very spatial and deeply musical.

Through

conversations with two Deaf artists during research, I learned that even if we

do not perceive sound waves in the same way, each of us has our own domain of

sonic experience. Both had cochlear implants — yet one used sign language and

the other did not. Even within the Deaf community, different sound conditions,

attitudes, and cultures exist.

A cochlear implant replaces the function of the

cochlea; while it allows Deaf individuals to share sound with hearing people,

noise sometimes occurs, and adjustments are needed for distance and volume —

meaning their experience cannot be identical to that of hearing people. It

creates a fluid identity between what is heard and unheard — sometimes leading

to loneliness, but also expanding a field of curiosity.

When

we met, each artist first described their listening condition — difficulties

perceiving speech when people wear masks, state of implant use, sound levels in

different spaces. These encounters helped me better understand the principles

of hearing: “Sound waves enter the ear and send electrical signals to the

brain.” A concept I always had to look up in a dictionary suddenly made sense

when embodied before me. Like Christine Sun Kim’s insights, both individuals

were deeply aware of sound — and knowledgeable about it.

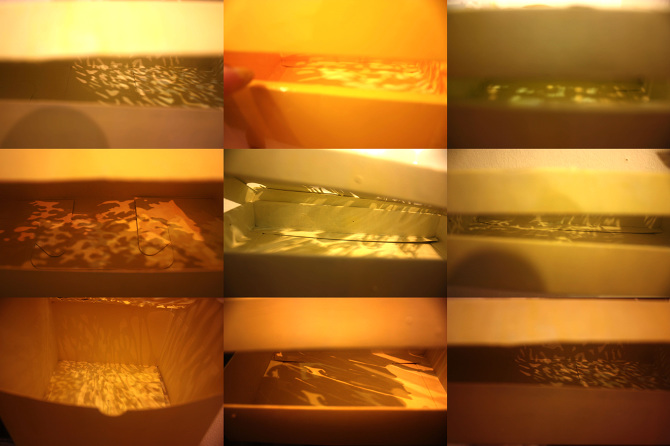

From

this, I learned that even if someone does not hear or experience sound in the

same way I do, it does not mean sound or music does not exist for

them. When sound waves exist, even if invisible, I can hear them — and another

person might see them or feel them as vibration. And perhaps beyond that — even

when waves are neither seen nor heard — there are still various inner currents

flowing within a person’s body and mind. Watching the rhythm of bodies in

motion, I imagine these unseen waves often. But if those imaginings remain

bound within the hearing person’s standard, they may become

a well-intentioned but ableist romanticization.

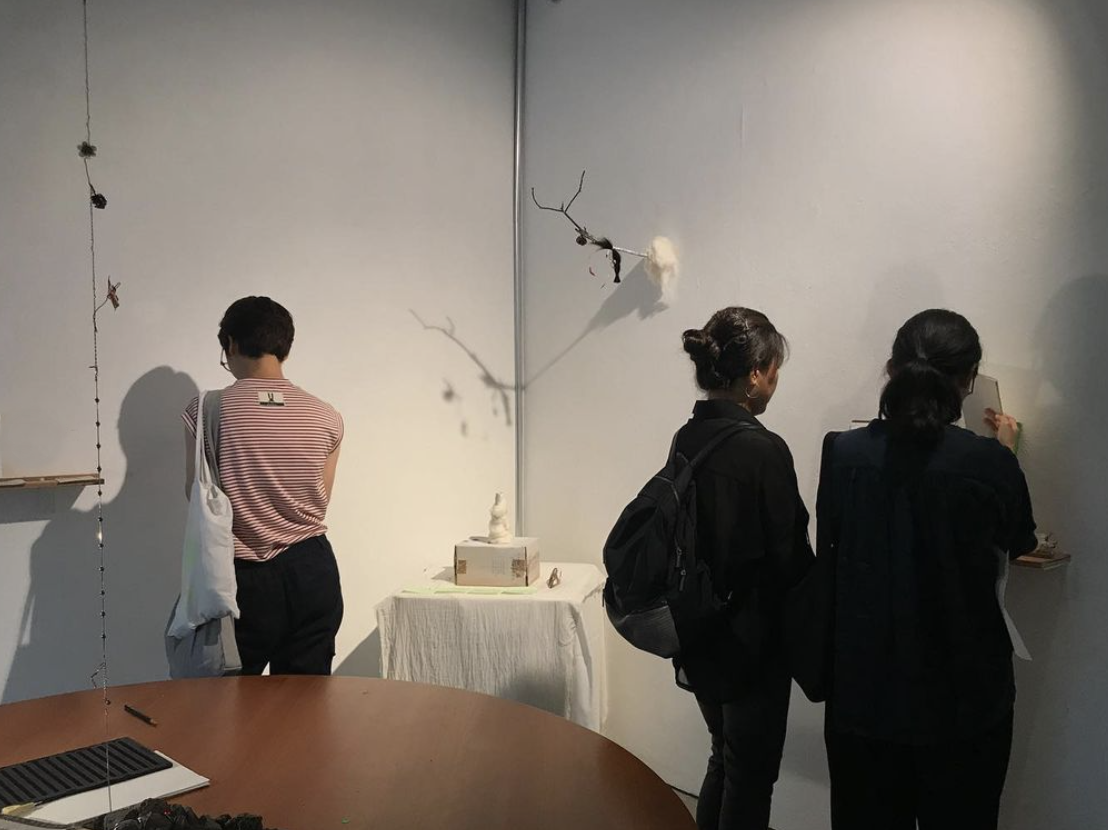

Once,

I attended the “Night of Flowing Communication,” an event supporting

communication services for Deaf individuals. A fellow artist who had shared

conversations with me about sound suggested I join. There, I met CODAs, Deaf

people with and without cochlear implants, and Deaf parents raising hearing

children. At the dinner table, as we introduced ourselves with excitement, I

said I was an artist working with sound — and conversation became hesitant. I,

too, suddenly questioned whether my approach to sound had been right. I decided

to listen more.

One

person was studying to become a psychological counselor for Deaf people. Due to

the pandemic, classes had moved online and required captioning — which posed a

heavy financial burden. The cost was significant — something that would be

difficult even for me to afford. I realized that Deaf individuals

must bear greater costs to do the same things in a sound-centered

society designed for hearing people.

“Could

the sonic space that feels important to me become an unnecessary imposition for

someone else?”

That day, I could feel in the air that I needed to keep dismantling and

re-examining my own assumptions about sound. This awareness came precisely

because I was a minority hearing person in a predominantly Deaf group. More

experiences where non-disabled individuals are invited as minorities in

disability-centered spaces are needed. Shifts in perspective — sometimes

easy, sometimes difficult — are continually necessary.

Art

can help expand interpretations of sound — enabling resonance without requiring

identical perception. I hope many pathways emerge where stories and

experiences, the songs embedded in our bodies, can be shared richly — even if

clumsy, uneven, or still in progress. And I must keep knocking, to make sure my

thoughts are not still trapped in rigid assumptions.