Such

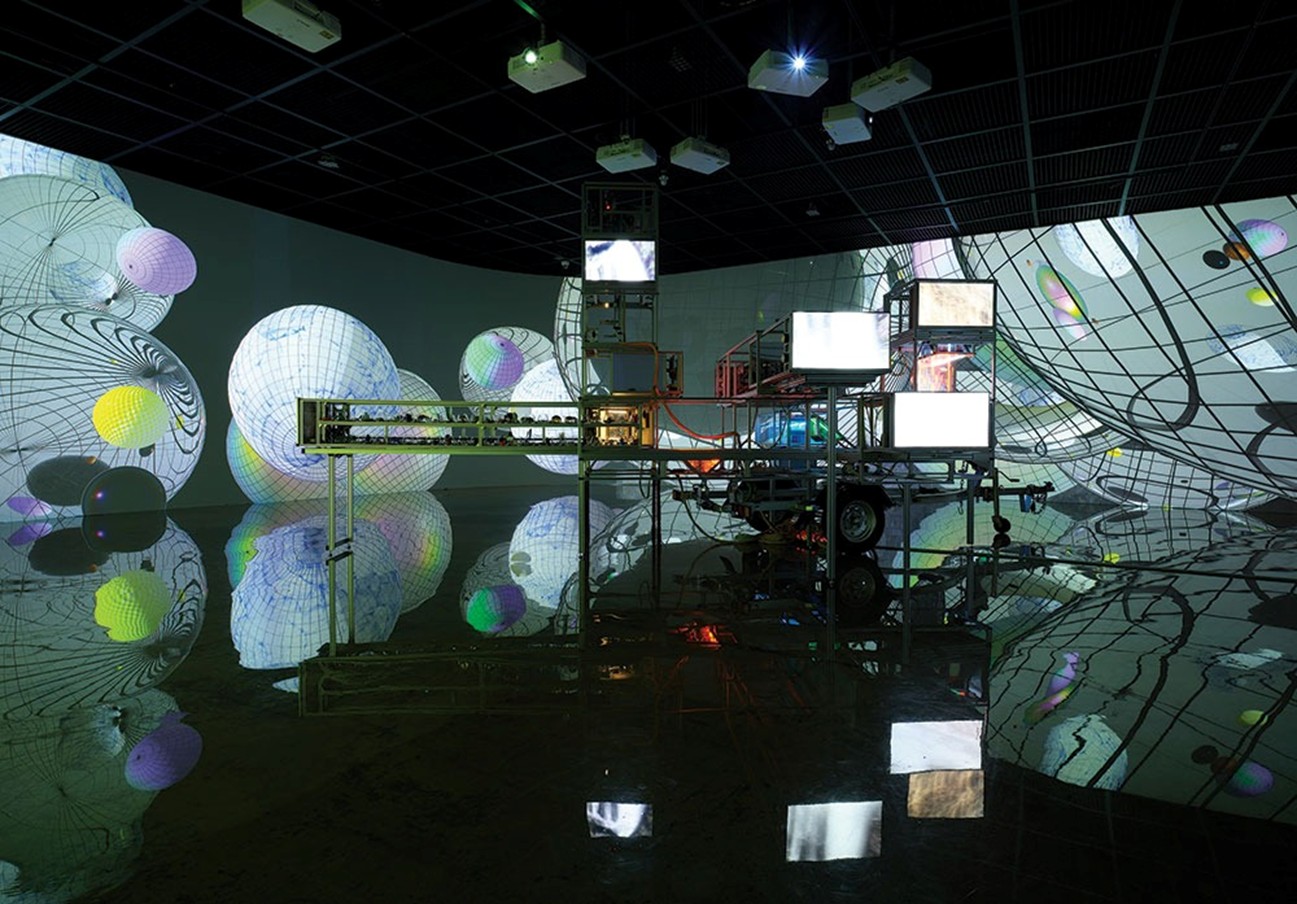

is the case for installations in this exhibition. From the boxwood tree, glass

outer wall, street lights to even apartments…. All models are 1:1 replicas.

However, if the models seem rather smaller than the actual life size, probably

it's because Hwang made them out of fabric, making them seem less solid, just

like a deflated balloon. Whether they would end up being inflated and hold

great dignity or shrink and sprawl out like an abandoned skin… we don’t know

which direction the air will take. Whether this place is new construction or

one to be demolished… we don’t know which direction the city will take.

Whether

citizens will move in here or be evicted… we don’t know which direction the

people will take. This uncertainty could have been the very destiny of the

city. A new construction and demolition, moving in and out from a city is not

an “all or nothing” event, but an event taking place “all at once, everywhere.”

However, when such event increases in frequency and intensity, the stones and

walls lose the power to keep and transmit history and memories of that place.

Accordingly, the nonhuman elements of a powerless city are reproduced by

fragile fabrics to exude a rather burned out and transient image. There is no

place for humans in a city with no accumulated history and memory. Time is

trapped in a revolving door and the present cannot go on because of the past.

Countless number of presents dissipates like grains of sand.

Perspectives

seen from fauna, flora, and minerals attempted by Hwang also take the direction

towards the actual building which holds the exhibition. The artist places

life-size replicas, modelled after a building’s pillar and inflated with a

fabric, among the original pillars and takes samples of the minerals used as

construction materials and the flowerbed plants used to landscape the

building’s surroundings, as if she had peeled off the building and revealed of

its bare skin. As such, the artist replicates, extracts and visualizes the

nonhuman elements constituting a city.

The landscape of 《Non-Affection for the City》 is not a landscape of humans but that of minerals, animals and

plants. This is not to simply oppose the human vs. nonhuman or encourage

denying what is human. Rather, it is seen as the artist’s attempt to redefine

the human-nonhuman relationship in an equivocal manner, unlike the modernist

humanism which called for mankind’s superiority over nature and environment.

Here, the modernistic dichotomies including nature/culture, human/animal, and

human/machine will be subject to review again.

In

summary, the works of Hwang hold a post-human attitude trying to overcome the

dichotomy-based hierarchy of human versus nonhuman. However, if the existing

post-humanism emerged from the technological and bioengineering breakthroughs,

the post-human sentiments of Hwang are somewhat similar, yet stand out in two

ways. First, Hwang’s works function regardless of scientific breakthroughs or

feats. The artist references old tools or techniques such as staircases, ladder

and slingshots to explore post-human possibilities.

The human-plant hybrid

sought by the artist is not related with modern genetic engineering, since it

involves wearing a “plant mask” combining an air-purifying plant with a gas

mask. Such low-tech sensibility of the artist illustrates that the post-human

agenda can be largely applied to our daily practice. Second, a unique sense of

humor can be found in Hwang’s works. Finger Fitness (2016)

or Plant Mask (2017) arouses a grin which is close to a

smirk.

In this exhibition alike, garments that hover around the same spot, like

a peeled-off skin placed among the seemingly sullen or gloomy apartments,

street lights, or building pillars make it hard not to smirk. On one side of a

wall inside the exhibition hall, can be found a hole, which seems torn apart.

Maybe it is a trace created from that smile, smirk. Or maybe it is a trace left

by a handful of “affection” which remains hidden in the 《Non-Affection for the City》.