What

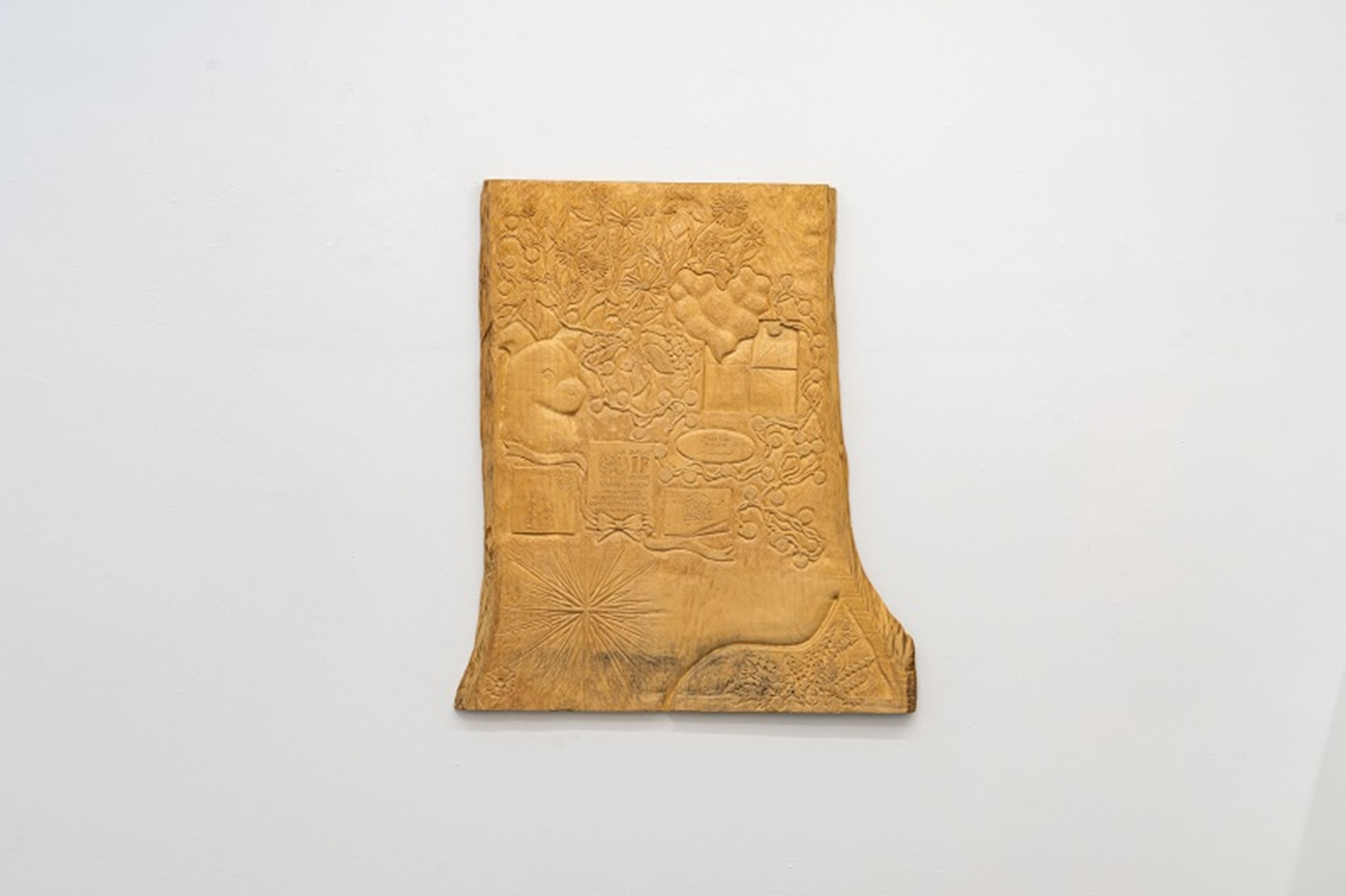

remains on the shell is the trace of nonverbal contact that once existed on the

boundary between hole and surface—skin. The artist’s hand must have repeatedly

tapped, pressed, and wrapped another person’s flesh. Plaster bandage dries

quickly and can be crushed easily; the act of wrapping the body would have

alternated between haste and suspension at every bump and strand of hair. The

moment when the living body was gently enclosed eventually leaves only the

shell, the body slipping out entirely. The remaining “shell” becomes the trace

of a collapsed, absent body—a form that remains like the possibility of a body

becoming a performance-less ritual text, the pursuit of its sculptural

potential.

The

shell evokes the thought of the body as ghost. The artist never mentions

“ghosts”—this is solely the viewer’s projection—but the white body

automatically recalls the wax tablet that Giorgio Agamben describes (citing

Plato and Aristotle) as a material that retains a trace even after removal, a

surface into which memory can be inscribed.[10] It recalls the soul once

contained in the shell, and the revelation it invites.

The

plaster bandage underlying Lee’s shell sculptures is materially unremarkable in

color, texture, and form. It is typically used for temporary molds and

discarded once the internal armature is restored. As material, it is secondary.

It softens when wet and breaks when pressure is applied. It is sculpturally

inconvenient. Yet, turned upside down, the disposable neutrality of the

material is ideal for the artist’s intention to strip away the symbolic

connotations of the human body and “sense it as a space where value categories

are softened.”[11]

At

this point, Lee prepares one more contradictory choice. The bodies she

investigated for this work evoke archetypes belonging to entirely different

temporalities than the provisional nature of plaster bandage: Donatello’s

David, Beyoncé’s performances and costumes, angel sculptures in the Vatican,

the Buddhist Medicine Buddha, Matisse’s Back reliefs, and sarcophagi of mummies

became the spectral prototypes of these shells. She then betrays this choice

once again.

“The highly subdivided conditions of the body as

hardware—retrograde or limited from the perspective of contemporary

sculpture—are recoded into concrete and detailed information values,” to be

“recycled” and “hacked.” The normative forms of the body become riddles that

disappear or appear in the casting process, generating events and sensations of

transformation: sexuality, the grotesque, iconoclasm, the trembling of skin

under pharmacological influence, and abstracted space.

Now

one body remains, laid across the floor in contrast to those standing. The

aluminum fragments, cast from the artist’s own body and reattached, raise a

question: Lee’s sculptures choose a path unlike the tradition of sculpture that

explores the artist’s body or the protagonist-like ego. These shells remind us

of the human as the “body,” merely a material that “comes to life and returns

to an inactive state.”[12] The plaster bandage evokes the processes of sealing

the corpse into a mummy or making a death mask. It touches upon the body after

existence is erased—either as the body after death or the body as object (which

again summons skin and touch).

The

corpse is sacred because it is an object; the living body also enters the

category of object, paradoxically grounding our rights to the body.[13] The

sculptural form of the “shell” began with the small ritual of casting the

hands, feet, and faces of close friends visiting the artist’s studio, and in

this exhibition became a visual language of carving bodily images out of a

single person’s physical structure and conditions of movement. Once fragmented,

the body is no longer perceived as a whole but as an object. When personality

is stripped away, the value of the body as an “empty shell” makes us reconsider

the human.

Text

by Jinju Kim (Curator, Seoul Museum of Art)

Notes

[1]

Although most of the works shown in the group exhibition (2022, N/A, curated by

Jeppe Ugelvig), the exhibition 《Transposition》 (2021, Art Sonje Center, curated by Haeju Kim), and the two-person

show Somingyeong x Eusung Lee 《Embassy》 (2021, Katalog Space) do not depict human bodies, they contain

elements that can be read as bodily characteristics (volume, skeletal

structure, bodily gesture). However, whether or not an actual human figure

appears is a clearly distinguishable point, and for that reason I do not use

these as evidence that the artist had already begun an exploration of the body.

[2]

Although obvious, when you imagine it, it is something like the A-shaped width

of broad male shoulders firmly planted in a vertical stance, the hat whose

graceful curve seems to hold the wind of the American West at its apex, the

guns holstered at the hips, and the focused gaze locked forward as he rides on

horseback.

[3]

Jesus was also a shepherd. Images of Jesus reimagined as a cowboy can easily be

found on the Internet.

[4]

For research on queer cowboys, I found this book: Chris Packard, “Queer

Cowboys” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). For an article on the appearance of the

queer cowboy in popular culture, see: C.S. Harper, “Why the cowboy has always

been queer as folk in pop culture,” May 23, 2023, Alternative Press, https://www.altpress.com/queer-cowboy-pop-culture-history-explained/.

[5]

Around 2021–2022, in English-speaking popular culture, a phenomenon emerged

where middle-aged male actors were affectionately called “babygirl” by fandoms.

A representative example is Pedro Pascal, who appeared in “Narcos.” See: Gavia

Baker-Whitelaw, “What does babygirl mean? And why does it refer to middle-aged

men?”, May 10, 2023, Daily Dot, https://www.dailydot.com/unclick/what-does-babygirl-mean-men-fandom/.

[6]

Was the expression—calling a sculptor a cowboy—suggesting someone who handles

mass and weight as if standing alone in the wilderness, enduring the weight of

the world? Is the gender implied in the cowboy separate from the sculptor’s own

gender or sexuality?

[7]

What makes “betrayal” so compelling in Lee’s work is the surrealism expressed

in her sculptural language. By comparison, the works in this exhibition are

strongly shaped by the realistic framework of the human body; that influence

cannot be erased. Although divided, interlocked, or inverted, the viewer still

cannot abandon the shape of the human figure. Should we assign value to the

leap from surrealism into figuration? Or insist that surreal elements still

remain? Neither development seemed particularly interesting.

[8]

Didier Anzieu, The Skin-Ego, translated by Kwon Jung-ah and Ahn Seok

(Seoul: Human Heukguk, 2008), 42.

[9]

Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, translated by Dayeon (Seoul:

Media Bus, 2022), 109–111.

[10]

Giorgio Agamben, The Signature of All Things, translated by Yoon Byung-eon

(Seoul: Jaum & Moeum, 2015), 154–159.

[11]

Unless otherwise noted, all quoted passages in quotation marks are from the

artist’s own words—most are taken from the artist’s notes shared via Google

Docs. July 2023.

[12]

Jean-Pierre Baud, The Stolen Hand, translated by Kim Hyun-kyung (Seoul:

Ieum, 2019), 128.

[13]

Jean-Pierre Baud, The Stolen Hand, 48–68.