Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Lee

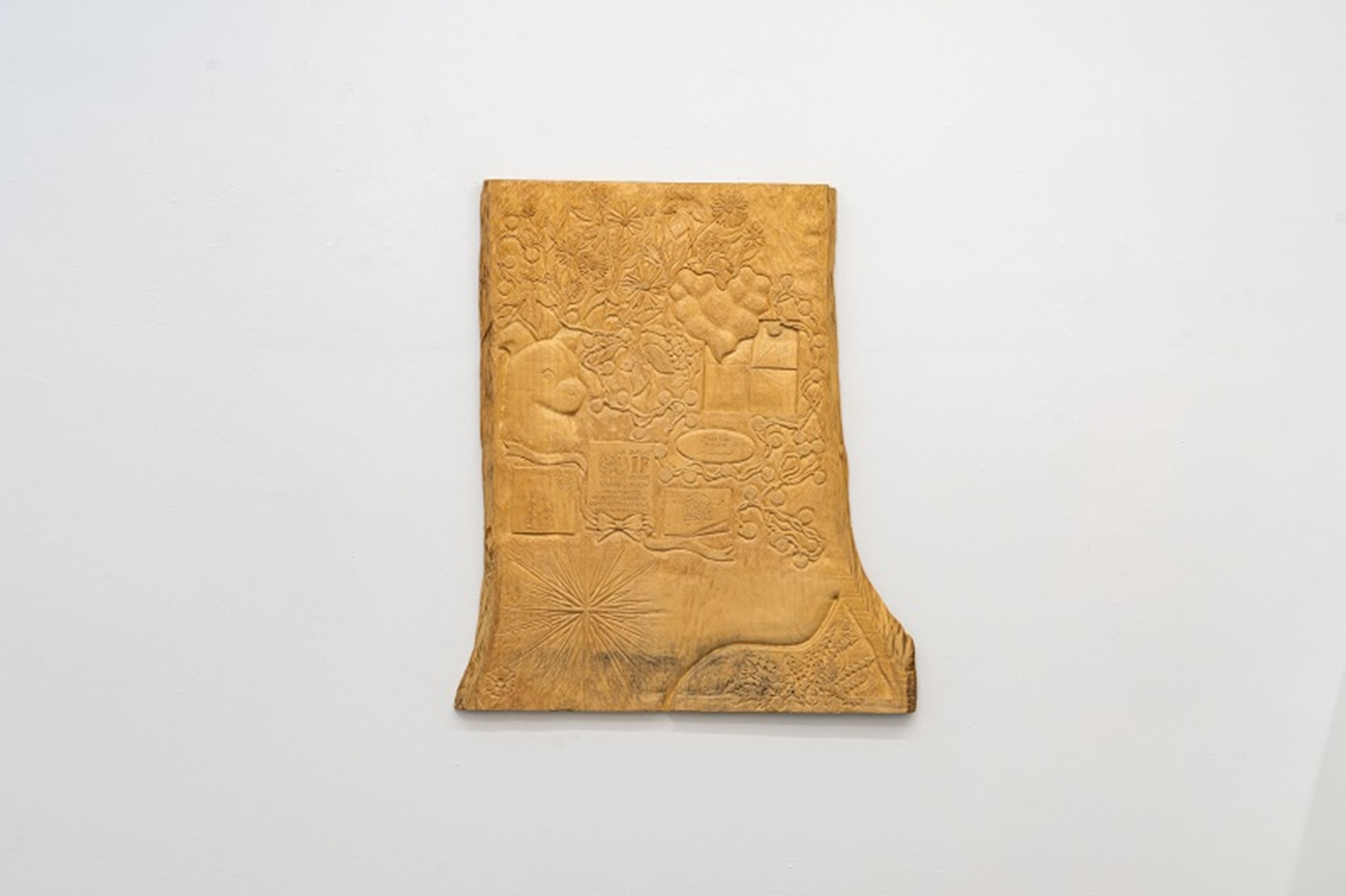

has held solo exhibitions including 《Epitaphs》 (TSA NY, New

York, USA, 2023), 《Cowboy》 (Artspace

Boan3, Seoul, 2023), 《Jane》 (Weekend/2W,

Seoul, 2019), and 《Floppy Hard Compact》 (Gallery175, Seoul, 2016).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Lee

has also participated in numerous group exhibitions, including 《Ringing Saga》

(DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul, 2025), 《Talking

Heads》 (Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, 2025), the 7th

Changwon Sculpture Biennale 《Silent Apple》 (Changwon, 2024), 《Open-Hands》 (Gallery Hyundai x Commonwealth and Council, Seoul, 2024), 《Foreverism: Endless Horizons》 (Ilmin Museum

of Art, Seoul, 2024), 《Sometimes it sticks to my body》 (WESS, Seoul, 2023), 《Memory of Rib》 (N/A, Seoul, 2022), 《Transposition》 (Art Sonje Center, Seoul, 2021), and more.

Awards

(Selected)

Lee

was selected as a SeMA Emerging Artist by the Seoul Museum of Art in 2023.

Residencies

(Selected)

Eusung Lee participated as a resident artist

at the Nanji Residency, Seoul Museum of Art in 2022.