Kim Sulki observes with curiosity

the present state of objects that traverse time and the narratives they carry.

Using acrylic, MDF, plaster, and other materials, she creates dragons—animals

from East Asian mythology—and refigures familiar fountain motifs commonly found

in public squares, as well as ancient reliefs. In doing so, she intersects

different temporalities of culture and narrative.

Although the contemporary

objects she constructs appear to be elevated like spiritual totems, they

simultaneously reveal distinct stories and layers, representing the volatility

and relentless pace of image-producing urban civilization. The forms and

materials shaped by the artist’s hand and body evoke eternity and

transcendence, transporting old narratives and beliefs into the present while

also recalling the fetishized status and function of commodities in

contemporary consumer society.

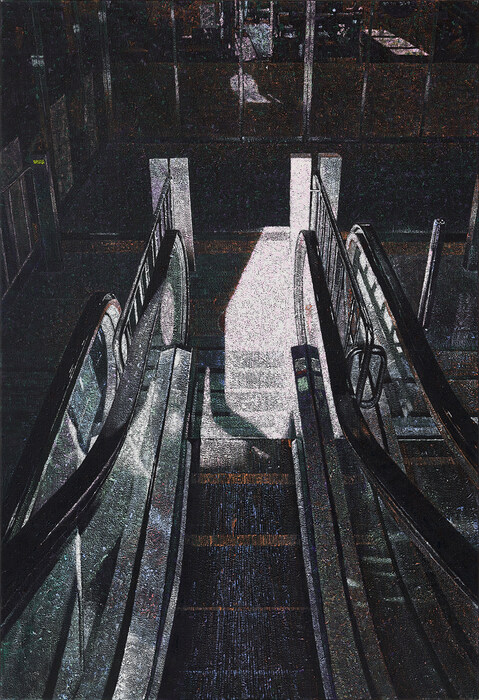

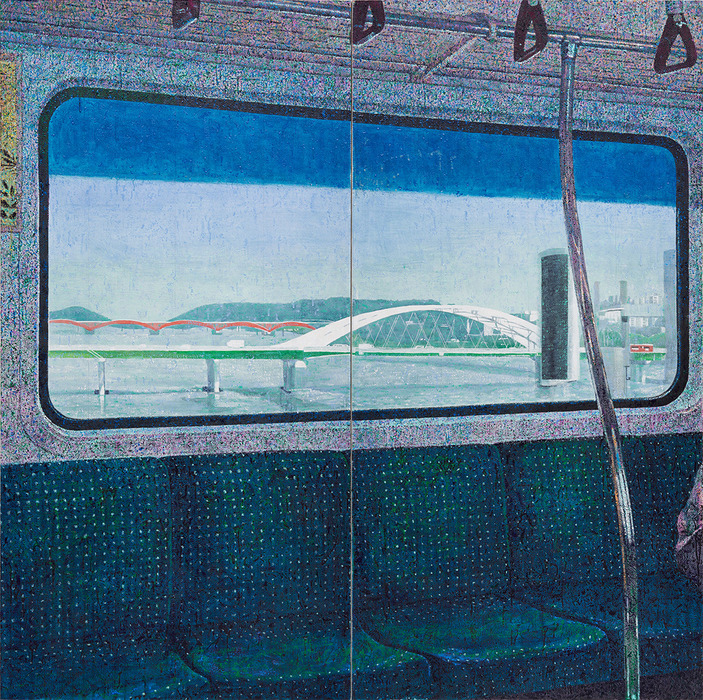

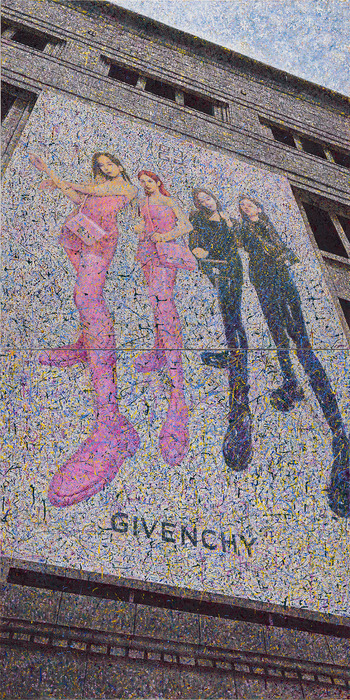

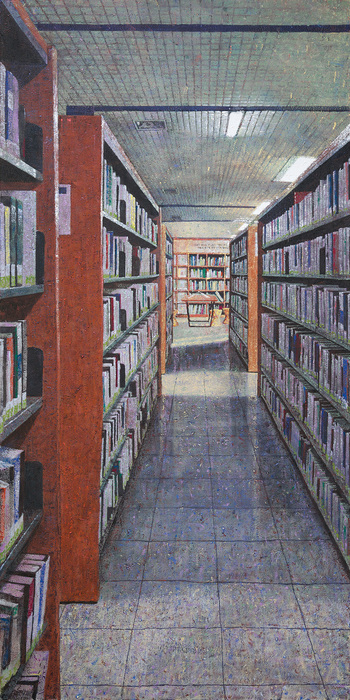

Hyewon Kim’s paintings appear at

first to be engrossed in the reproduction of digital images. Working from

photographs taken on her smartphone, she sets up a manual and process that

minimizes dramatic brushstrokes or personal emotional expression. Her motifs—public

telephones and vending machines in subway stations, the interior of city

buses—are scenes too ordinary and faint to seem worthy of being framed.

Yet her

works reveal the surface, materiality, and even the events of

painting, differentiating themselves from the pixels and resolution of digital

photographs. Beginning with a watercolor base and layering gouache mixed with

gum arabic onto the surface, she produces painterly (and even craft-like) forms

and strata that release the work from strict representation. This detachment

draws attention to the processes and experiences of painting—color and

materiality, viewpoint and distance, the movements of the hand and body.

Yoon Jeong-e experiments within

sculpture by combining two modes of sculptural operation: carving, which

removes material to create form, and modeling, which adds and builds up

material. Her sculptures, where masses of material intertwine with traces of cutting,

slicing, and kneading, disturb the legibility of both subject and process,

gathering peripheral afterimages and spatial gaps.

Moving between parts and

wholes of the body, between plane and volume, between small pieces and large

ones—and through the firing of clay in the kiln—her work focuses on the very

process of temporal shifts and transformation, incorporating them directly into

sculptural practice. The sculptures that stand upright in the exhibition do not

present fixed forms or content; instead, they traverse the boundaries between

inside and outside, skeleton and flesh, self and object, materializing the

intervals where form melts, displaces, and resists completion.

Lee ByungHo, drawing on Rodin’s

methodology, has long presented human figures assembled from parts—bodies that

cannot become a singular whole. Rather than treating existing works as

definitive originals, he has cut, duplicated, and recombined them into new

works, extending this methodology beyond the body into his entire practice.

This has expanded further through digital replication and 3D printing.

Since

2020, for Eccentric Abattis, he has scanned his

previous works in 3D, adjusted their scale, detached certain parts into

abstract forms, or merged them into assembled masses. In Eccentric

Scene (2023), shown in this exhibition, he reverses the process

by bringing back the original body—the one already duplicated and

recombined—and again merges it with scanned and modified components,

reaffirming a perpetual cycle within his own methodology.

Lee Sojung’s paintings intersect

different worlds—sometimes even contradictory ones. Over time, she has

experimented with ways of using ink that exclude its accidental effects, and

has layered automatic, chance-generated images over familiar symbols. Her

recent works translate situations in which pigment bleeds and seeps

uncontrollably into inevitable images, likening these uncontrollable situations

to personal experiences.

She wets previously used paper with ink and presses it

onto the surface to reproduce chance; she organizes forms using acrylic paint

alongside traditional East Asian pigments. She also utilizes wax so that

patterned structures on the back of the canvas and accidental forms on the

front appear simultaneously. Moving across different painting methods,

materials, and concepts, her works coordinate the proliferation of images that

transcend fixed media and spacetime—an expanded condition of the pictorial

plane.

Jun Hyerim adopts the iconography

and compositional methods of her earlier paintings as a kind of open-source

material. From Chinese landscape paintings depicting idealized spaces, to

Arcadian scenes from Greek painting, to brightly colored ukiyo-e, barbershop

paintings, and even the Japanese manga One Piece, Jun’s

work invokes painting styles and techniques from various cultures and eras.

Yet

rather than faithfully following the brushwork or ideas embedded in each

source, she focuses on appropriating them as-is, ultimately producing paintings

that seem awkward, unrefined, or intentionally “unskilled.” The reinterpreted

Guo Xi, Koo Young, and Tiepolo are dismantled and revived within her chosen

frameworks of excess temporality. In doing so, Jeon simultaneously signals the

historical nature of each source while betraying established hierarchies and

positions, allowing a multidimensional temporality to surface.

Choe Sooryeon presents subjects

commonly regarded as classical or traditional in strange and uncanny forms. The

celestial maiden from East Asian folklore does not appear in her work as a

graceful and virtuous woman, but rather as a haunting, sometimes sorrowful figure.

Beyond this, Choe faithfully studies and manually transcribes fantastical folk

tales—even the absurd ones—and also recreates scenes and lines from the (mostly

Sinophone) dramas and films she has enjoyed.

Through this, she lays bare the

structures of traditional images and narratives from Korea and East Asia, as

well as the rigid preconceptions that support them. Although her practice seems

to learn and imitate inaccessible subjects—Chinese characters, classical

imagery, myth—the work simultaneously reveals the atemporality and absurdity

embedded in what is considered universal or self-evident, ultimately summoning

the not-so-distant faces of the present like ghosts.

Curating/Writing: Kwon Hyukgyu

[1] 《Unmonumental》 was co-curated by Richard

Flood, Laura Hoptman, and Massimiliano Gioni.

[2] The

four-part exhibition unfolded as follows:

– 1. Unmonumental: The Object in the 21st

Century (2007.12.01–2008.03.30)

– 2. Collage: The Unmonumental Picture (2008.01.16–03.30)

– 3. The Sound of Things: Unmonumental Audio (2008.02.13–03.30)

– 4. Montage: Unmonumental Online (2008.02.15–03.30)

[3] Richard

Flood, Laura Hoptman, Massimiliano Gioni, Unmonumental: The Object in the

21st Century (London; New York: Phaidon in association with New Museum,

2007).

[4] In

relation to this, critic Roberta Smith noted that 《Unmonumental》 could evoke anti-art movements

such as Dada and Surrealism insofar as it rejects completed form and

marketability. She also observed that the rough finishes and deliberate

“un-skill” found in the works—rather than polished surfaces and spectacle—could

be linked to Arte Povera, and that the use of found images for reproduction and

recombination could be associated with Pop Art.

Roberta Smith, “[Art Review: ‘UNMONUMENTAL’] In Galleries, a Nervy Opening

Volley,” The New York Times (Nov. 30, 2007), https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/30/arts/design/30newm.html

[5] Laura

Hoptman, one of the curators of 《Unmonumental》, also described the exhibition

as following the genealogical line of MoMA’s The Art of

Assemblage (1961), curated by William Seitz, which presented assemblage as

a defining trend of contemporary art of its time. Interestingly, Hoptman later

curated Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal

World (2014.12.14–2015.04.05) at MoMA, a show that revisited the tradition

of twentieth-century painting to present the state of contemporary painting.