I

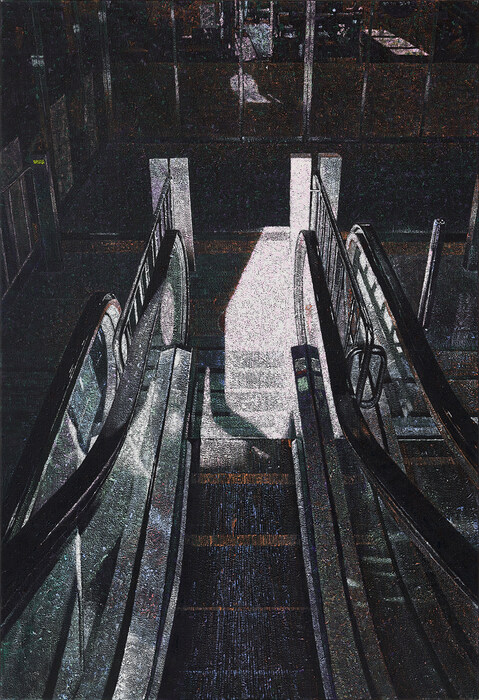

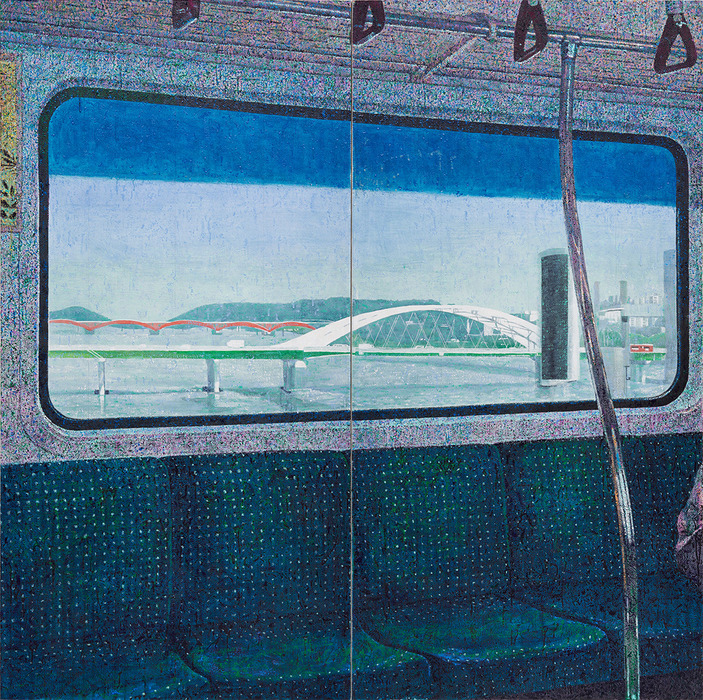

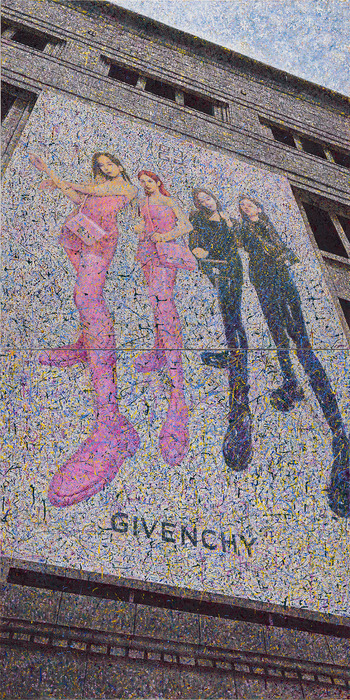

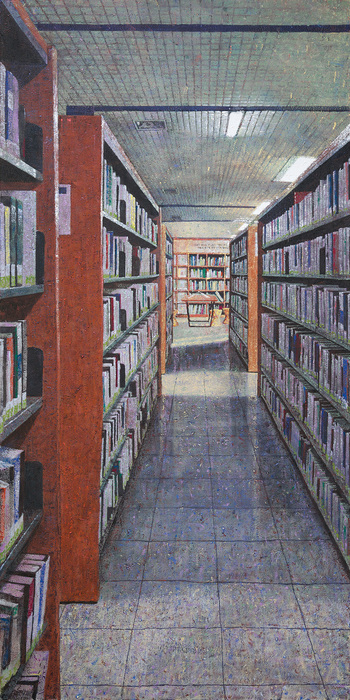

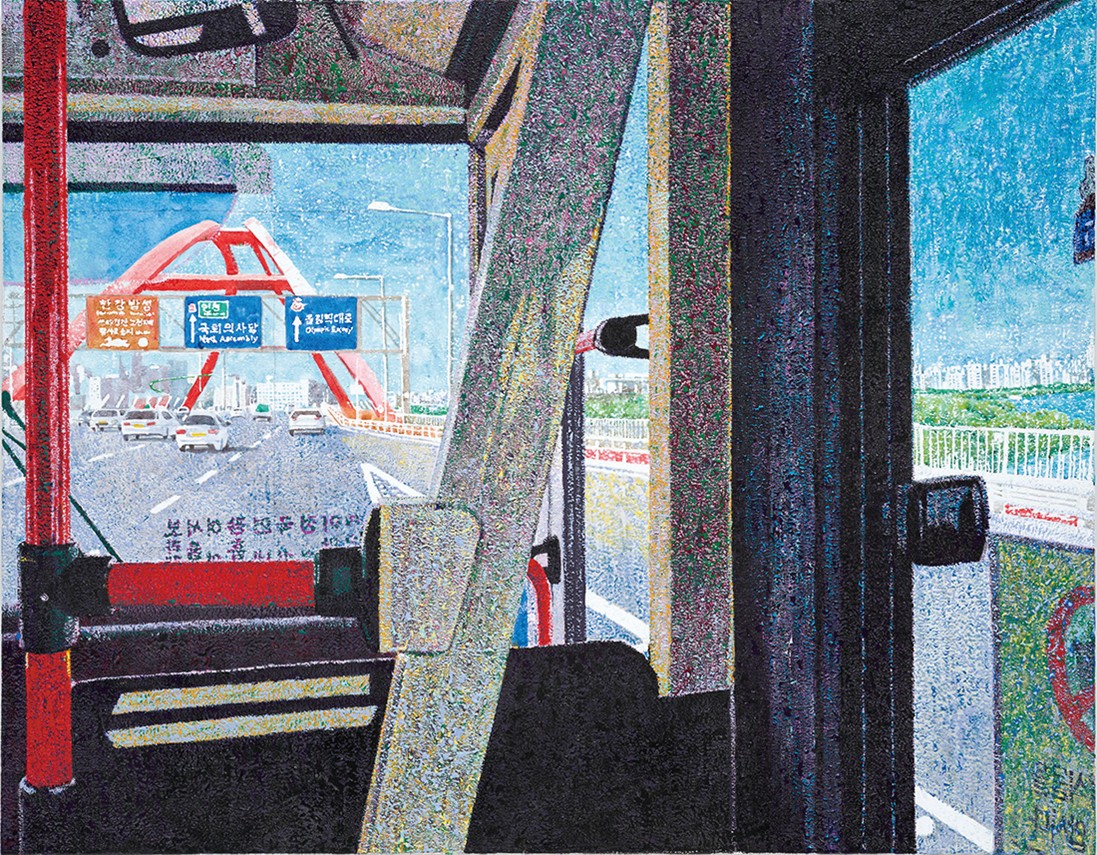

believe that anyone who encounters Hyewon Kim’s paintings will likely find

themselves drawn to them. She seeks out the things she frequently

sees—ordinary, everyday landscapes—and captures them in paint. Shelves in a

library, the bus she always takes, or the scenery outside a subway window

become the subjects of her work. Yet when one approaches these seemingly

ordinary images, an unexpected scene unfolds. Layers of pigment—colors and

delicate textures that were not visible from afar—come into view. From the

surface of everyday landscapes emerges an exceptional kind of beauty.

One

might say that her paintings “reveal” the colors and textures hidden within the

everyday. However, once we observe the way she paints, the word “reveal” begins

to feel somewhat strange. Kim describes the landscape in watercolor and then

adds layers by mixing in acrylic medium. Thin strata of paint rise, one after

another, through meticulous brushwork. The pigments accumulate and accumulate,

but never so much that they entirely obscure the image—only just enough to veil

it precariously. Rather than “revealing” something, her method feels more like

“covering” it. As layers accumulate and partially conceal the image, the

familiar sensibility with which we view daily life is peeled away, and a new

landscape paradoxically emerges on the surface of the canvas.

I

once found Kim’s artist notes particularly intriguing. To summarize a portion:

“Squeezing paint, calculating color, selecting a brush of the right size, and

applying paint to the surface makes me forget that I am depicting a particular

object. As I mechanically spread paint across the canvas, the thought of

drawing something approaches zero, and only the movement of my hand stimulates

my vision.” Contrary to the expectation that she would approach painting with a

creative, “artist-like” attitude inspired by daily life, she instead describes

her practice as one shaped by mechanical, repetitive motions. This repetition,

in which thought dissolves and only movement remains, resembles labor far more

than an artist’s creative act.

It

is important to note here that Kim also has a deep interest in handicrafts such

as embroidery and knitting. Art critic Jungwoo Park, who wrote about her first

solo exhibition 《Thickness of

Pictures》 (2022), observed that the delicate

sensibilities she developed through working with craft practices are reflected

in her method of painting. Situated between creation and labor, handicraft

forms an inseparable sensory foundation for her work. Kim’s paintings arise

from the convergence of three different modes of action—painting, handicraft,

and mechanical, repetitive movement—coming together almost accidentally.

Philosopher

Hannah Arendt famously divided the fundamental activities of human life into

three categories. To quote this widely referenced distinction: first, there is

labor, the biological activity directly tied to human survival. Then there is

work, the activity that constructs an artificial world apart from nature. Labor

and work both serve to fulfill human needs and desires. Finally, there is

action. Action is not an activity for necessity or desire but one for freedom,

and it is a privileged realm in which human agency and uniqueness can be

revealed. Arendt’s concept of action has often been invoked to explain the

essential nature of artistic activity. Yet in Kim’s painting practice, action

does not feel like the creative act of self-realization—it feels closer to a

form of labor. As she works, she suddenly confronts the contradictory aspects

hidden within what we typically think of as free, privileged artistic action.

Anyone

who encounters Kim’s paintings will likely enjoy them. The canvases, filled

with practiced, meticulous strokes, offer delight to the viewer. I, too, found

her works beautiful when I observed them up close. But this beauty does not

originate from the artist’s intention. If beauty is present, it is merely an

accidental outcome appearing at the end of tedious, unconscious hand movements.

Kim’s paintings do not beautify daily life; instead, they point to the fact

that daily life is built from dull, mechanical repetition. From this

repetition, coincidence may arise—or it may not. Whether the paintings are

beautiful is, in the end, not important at all.