Since

her debut solo exhibition in 2017, Jeong Juwon has held five solo shows, each

reflecting the sentiments and thoughts of its time. Her early exhibitions

revealed her anguish over art as labor—an effort to prove sincerity and

confront the social precarity of being an artist. Her unexpected trip to

Mongolia, chosen as a way to distance herself from the frantic art scene of

Seoul and its relentless demand for diligence, led her into self-reflection on

usefulness, a contemplation that carried over into her next exhibition 《Starry, starry ghost》(2020, Gallery 175). By

this point, Jeong seemed to have decided to build a parallel world of her own

pace rather than align herself with social labels or measures of success—as if

discord were her destiny.

The solo exhibition 《Go Up to

Your Neck in Love》(2021, Onsu Gonggan) directly

preceded and conceptually connected to the current show, presenting works that

delved more explicitly into the theme of love. Afterward came a period of

material exploration centered on the properties of glue-tempera, culminating in

《Immortal Crack》(2022, GOP

Factory). Though eight years have passed, the artist still carries the question

of her foundation— her roots—continuing what Jack Halberstam calls “staying

lost.”[5] Here, to “stay lost” does not bear a negative meaning but rather

implies a creative act of seeking new possibilities within a world of different

shapes and tempos—of groping through the dark to find forms of invention.

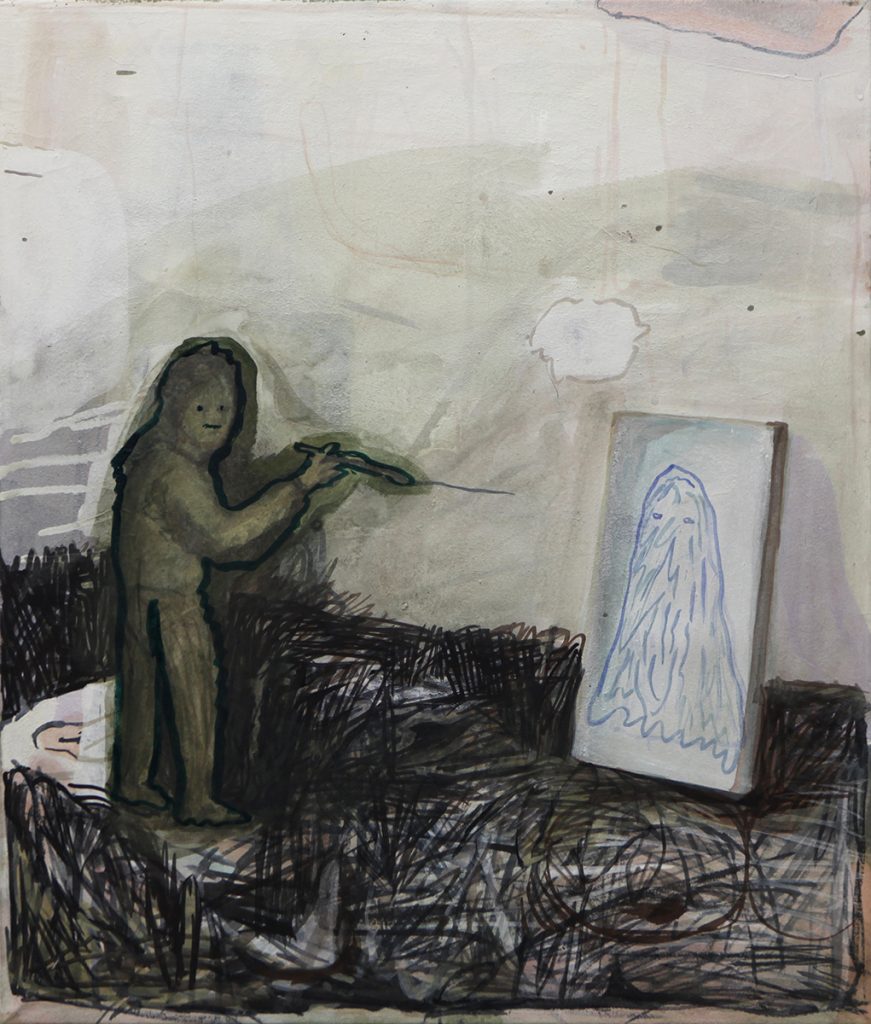

Let

us look at her lines. The lines in Jeong Juwon’s paintings resemble water

stains. They sometimes appear like traces of tears, and indeed faces that seem

to be crying often surface in her work. These water-stain-like marks reflect

both the emotional undercurrent of her practice and the results of her material

research. The unavoidable cracks produced by the glue-tempera mixture[6] were

once regarded by the artist as an obstacle.

Yet now she embraces them as a

distinct feature, adjusting them flexibly by applying thin layers of pigment

and allowing the cracks to settle naturally within the composition. What she

once perceived as failure has become a means to reorganize existing

perceptions, conventions, and norms—an attitude that aligns with her broader

artistic direction. Her drawn lines are not sharp or decisive but hesitant and

blurred—not to divide, but to soften. When a clear form emerges amid these

overlapping lines, and when a moment of humanity flickers beyond the shape, the

work reaches completion.

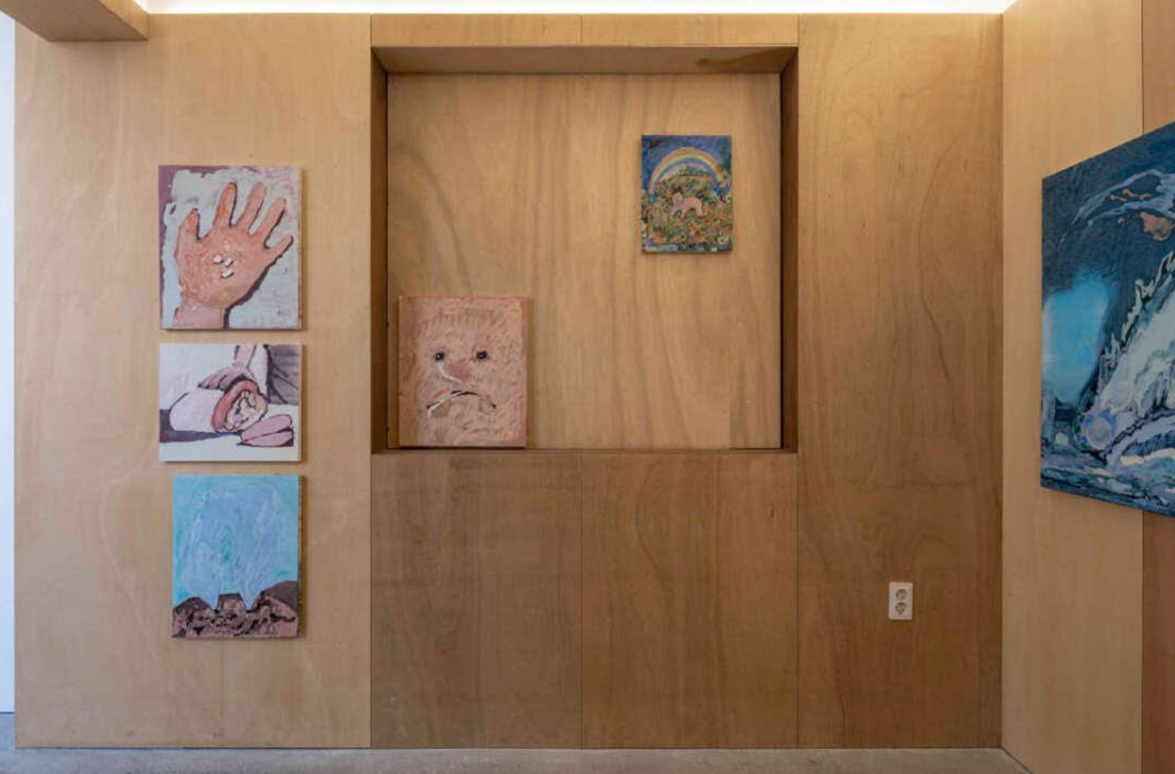

On

one side of the gallery stands an awkward sculptural structure, Great

Wall (2024), which can be read in the same context. It is a kind of

partition meant to hang paintings on, yet this brick-like wall, roughly woven

together with a 3D pen, occupies neither the center nor effectively blocks

anything; it merely supports a few small paintings.[7] In its very ambiguity,

it performs its role, guiding the viewer’s path and perception through the

space.

Looking

at Nine Bodies, Four Hands (2024), one can once again sense

Jeong Juwon’s attitude toward art and life.

Perhaps it resembles the state of Firm

and Healthy Body (2024): rooted firmly in the ground, stacking

fragments into one large “existence.” It matters little what time each fragment

has endured; what counts is that every fold, callus, and shell bears witness to

experience. Behind the surfaces of Jeong’s paintings lies a profound

tenderness—an infinite time accumulated through hesitation and persistence.

Standing before her completed works, one traces that immeasurable duration he

must have spent, layer by layer.

Notes

[1] The essay’s title quotes the song A Dance Alone by the Korean band Sister’s

Barbershop.

[2] Henri Bergson, Le Rire (1900); Korean translation by Jeong Yeon-bok,

Moonhak-gwa Jiseongsa, 2021, pp. 34–36.

[3] Ibid., p. 28.

[4] Trees and branches in Jeong’s work often appear as extensions of the

body—like crutches or two-person race straps—sometimes stacking as fragments

into a single solid form, or evoking the jangseung (totem pole) that

traditionally guarded villages and marked paths.

[5] Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (2011); Korean translation by Heo

Won, Hyunsil Culture, 2024, p. 62.

[6] Except for her 2020 show, Jeong has consistently worked with traditional

Korean pigments and kaolin mixed with glue as a binder. She has referred to

this medium as “glue-tempera,” a hand-made paint created by mixing pigment with

binder. Due to its variable viscosity and density, her paintings inevitably

develop fine cracks. Her previous solo show 《Immortal Crack》(2022, GOP Factory) focused

intensively on this sense of fragility and powerlessness that cracks evoke.

[7] Ironically, the construction of this wall required an enormous amount of

labor and time. “The Great Wall” is thus both a truth and a joke.