Objectified or Divided Landscapes

If

the canvas is a thing, painting mystifies it as an empty sign. Conversely, if

painting itself is a thing, the canvas concretizes it as an empty signifier. Haevan

Lee precisely and swiftly anchors his images onto the canvas in various

forms—this precision is one measurable point amid the differences in the

artist’s production, which resists being unified under a single subject or

style.

Thus,

rather than serving as the boundary of a vanishing explosion, the canvas

becomes a sign that distinctly delineates the boundary between itself and

reality. In other words, Lee constructs painting not as an image, but as an

objectified canvas—as the installation of an image.

《Goliath, Tank》(2018) consists of paintings

rendered on wooden boards cut to the outlines of objects resembling tanks, each

equipped with pendulums that swing incessantly. The “wooden board as canvas”

momentarily divides the world where painting stagnates. (Here, we may

conceptualize the “canvas” not as the literal fabric used for oil painting, but

as the flat plane that presupposes the possibility of painting and, at the same

time, as the object that enables its installation.)

The

form of the wooden board, as another signifier, refers to the tank in the

title, the site of the exhibition—Peace Culture Bunker—and even the theme of

the exhibition itself. It clarifies the signified of the work, overturning or

subordinating the details of painting into a kind of background. The pendulum

attached to the tank-shaped structure swings rapidly, suggesting that the

stagnant time since the Korean War must be accelerated in order to be measured

in the present.

On

the surface, the form (the canvas) seems to confine the image (the painting),

and the image appears to lose its individuality and inherent power. Yet, could

such an inversion between figure and ground not be seen as the formation of a

single plane? Lee’s painting is not segmented within a large plane, nor merely

divided by the frame; rather, it resides within the boundary. In fact, the

artist does not paint on a square canvas and then cut it apart—he paints

directly on canvases already cut into shape.

Thus,

division does not function as the concealment of what has been removed, nor as

an imagined possibility of visibility, but instead constructs surface and world

through the curved seams of those divisions. The form goes beyond composing the

world—it reorganizes the very perspective through which the world is seen. Such

a method of “division” transforms painting into a signifier of the object

itself, an installation composed of the image-canvas.

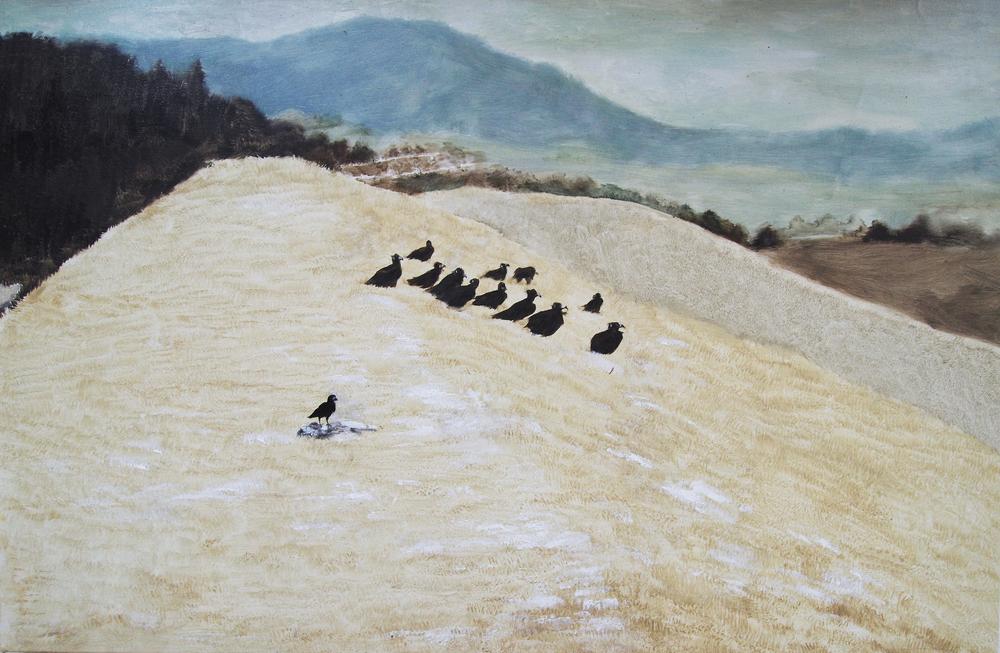

At

Hongcheon Museum of Art, the series of nine works titled On the Road presented

small paintings on square canvases. These were reconfigurations of images

conceived during the DOPA Project’s journey across Siberia, combined with

scenes inspired by the artist’s observations in Hongcheon. The phrase “TRANS

RAINBOW,” repeatedly written across the canvases, appears not from a frontal

view but at a diagonal angle, emerging through a mode of viewing that involves

walking along the works—connecting them, as if linking the bodies of train

cars.