Stones, shards of glass, mud, falling rain, cliffs, weary feet—

When these individual words are joined together with commas and periods, an

immediate scene takes shape in the mind. Each element obstructs movement,

causes injury, and prevents one from advancing. Facing the edge of a cliff, did

the person turn around in search of a new path? Or did they slip on the

rain-soaked ground and fall below? Perhaps, burdened by exhaustion and rain,

they never ventured outside at all.

Eunsi

Jo constructs narratives by placing visually and situationally similar elements

within a single frame. She uses the viewer’s cognitive urge to analyze and

interpret these forms to trigger imagined events and unfold their progression.

In Distressed Day, for example, we may link the red objects

falling from the tree with the violent tools arranged on the right side of the

canvas, assuming that the work depicts an act of violence against the tree. The

title reinforces such an inference.

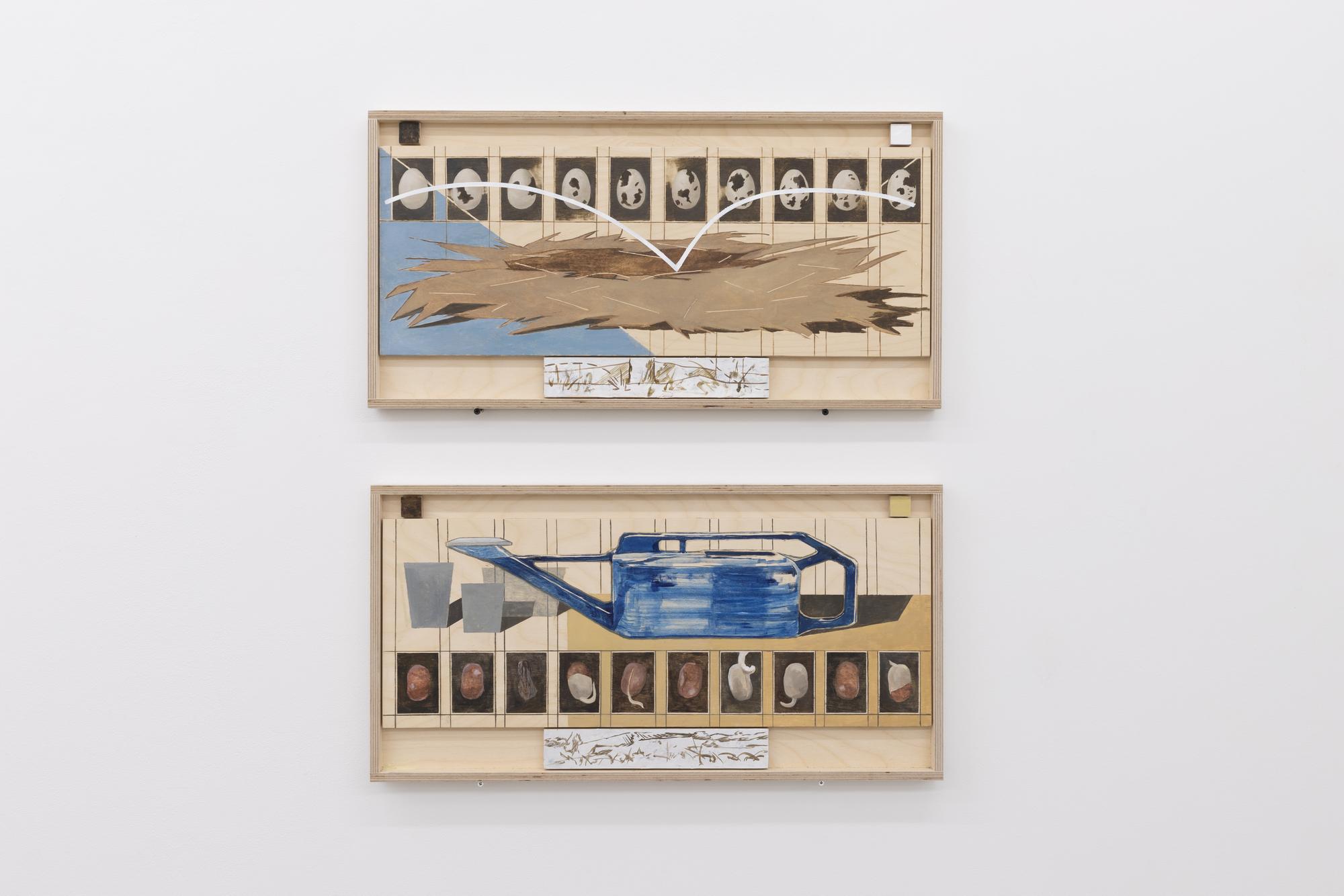

Similarly, Have One’s Retreat Cut

Off employs compositional elements that operate as the mechanism of

an incident, connecting a series of rectangular frames into one continuous

narrative. The silhouette of a fighter jet crossing the sky recalls the scene

of a flight-shooting game, inviting the viewer to predict what happens next.

What, then, compels the artist to repeatedly stage these sequences of events?

Forest and trees, fruit and bombs, meteorites and rifles, volcanic

eruptions and sprinklers.

The answer may be found in The Providence of Nature. Once

again, the canvas is divided along the central image of a gun, with a red

curved line that appears to trace the order of unfolding events. Yet the

viewer’s gaze moves from the egg at the bottom to the bird above, and back to

the egg, circling endlessly without a fixed beginning or end. On the left, a

rectangular frame depicts a bird preying on insects; on the right, another

shows a hunter aiming at a bird. The same act of hunting repeats, with only the

targets changing. Following the curve, the dead bird hatches again from the egg

to resume its predation.

This

is a world of endless cycles of birth and death. Yet the work does not imply

that civilization and humanity—having invented the slingshot—stand apart as

ultimate predators. Rather, by revealing the cyclical and chain-like structure

of these connected events, which reappear in different forms and cannot be

assigned a singular beginning or end, Jo shows that all share a common root.

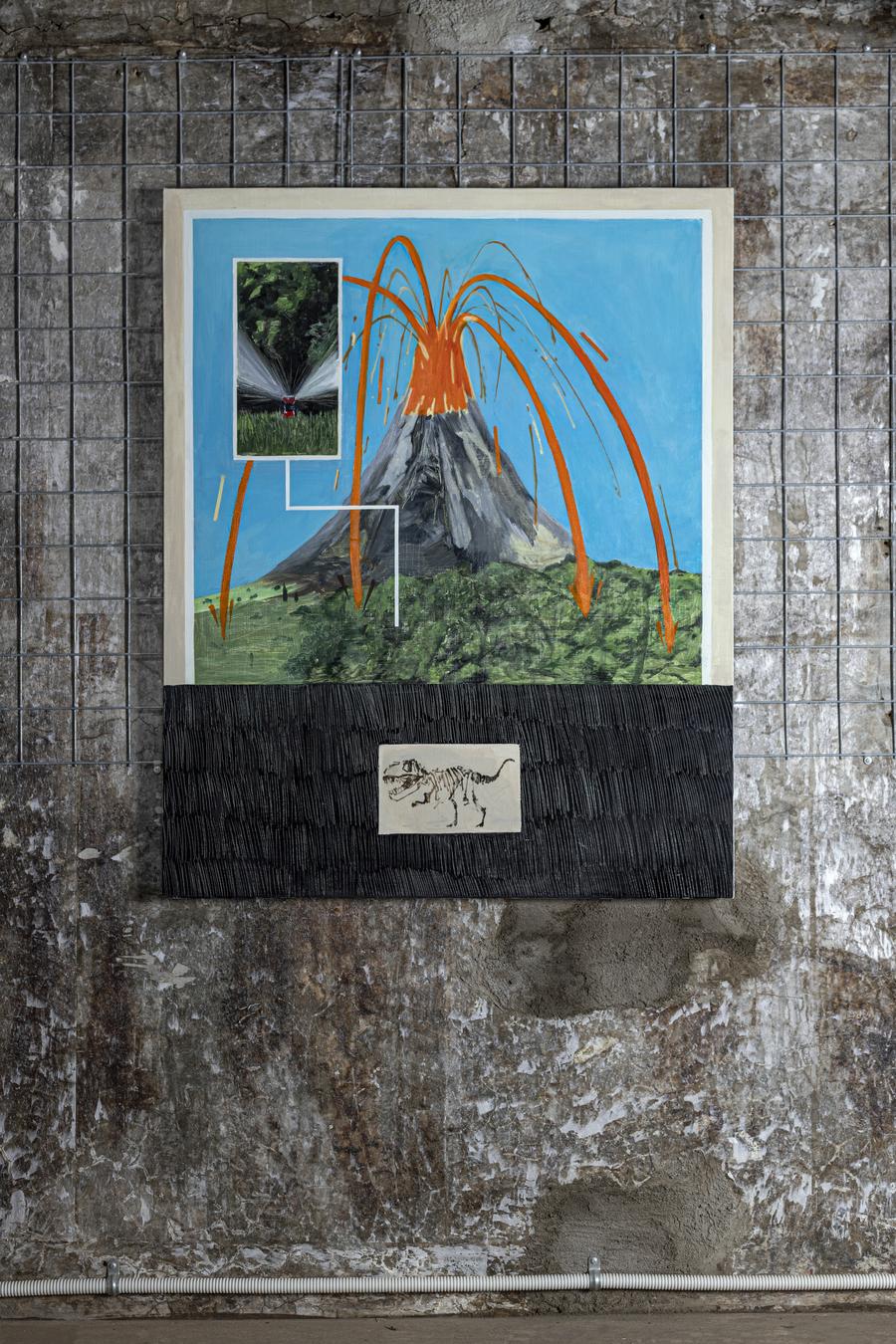

In

Same Way, the visual resemblance between an erupting volcano

and a spraying sprinkler reinforces this notion. As implied by the dinosaur

bones below, one engulfs life into death, while the other promotes growth and

vitality. Yet both display an outward burst—a strikingly similar motion. This

repetition of resemblance between eruption and emission signifies that

destruction and creation, extinction and regeneration, are not dualistic

opposites but parts of a single continuum.

The

divided frames across her canvases depict confrontations—between nature and

civilization, animal and human—not to emphasize difference, but to reveal that

they belong to one and the same world. Borrowing the artist’s own visual

metaphor, we might say that we are all trees belonging to the forest as a

whole.