(Excerpt)

So the story goes like this: as the electrical signals of hardware and the

commands they carry leap into the realm of language and masquerade as software,

games are captured by quantifiable cybernetics. Of course, even before games

ran on computers and were mediated by video, “play” always contained some

arithmetic and rules. Sometimes players, trusting that everyone knows the

rules, calculate possible tactics in their heads; other times a moderator

thumbs through a rulebook and scribbles down dice-roll math while mediating

among participants.

In such situations, the machine steps in as a calculator

that can handle arithmetic and rules too strict or complex for the human brain.

Over the past century, proportional to computers’ increasing processing power, the

scale and density of those rules and calculations have swelled, and thick

layers of translation systems have been wedged between machines and humans to

mediate their languages. This is precisely where a misalignment between reality

and fiction likely arose. In “On Software, or the Persistence of Visual

Knowledge,” Wendy Hui Kyong Chun points to two kinds of concealment produced by

software’s invention on the hardware side.

One is the language of machines—the

electrical signals coursing through logic circuits become like ghosts in the

machine rather than the computer’s nervous system once they are abstracted,

symbolized, and translated for humans. The other is women’s labor—those

astonishing skills that once wove strategies mediating humans and machines are

replaced by convenient automated control systems and likewise become ghosts,

not bridges, within the system.

With

the machine apparatus and its expert interpreters hidden, the computer has

become a mysterious object that the average user cannot easily understand

beyond accessing interfaces and using software at the surface. No one in their

right mind could keep pace with the terrifyingly unnecessary acceleration of

information technology. Perhaps computers have long since outstripped games,

and at some point games outstripped their users—indeed, perhaps both games and

users have been swallowed by computers.

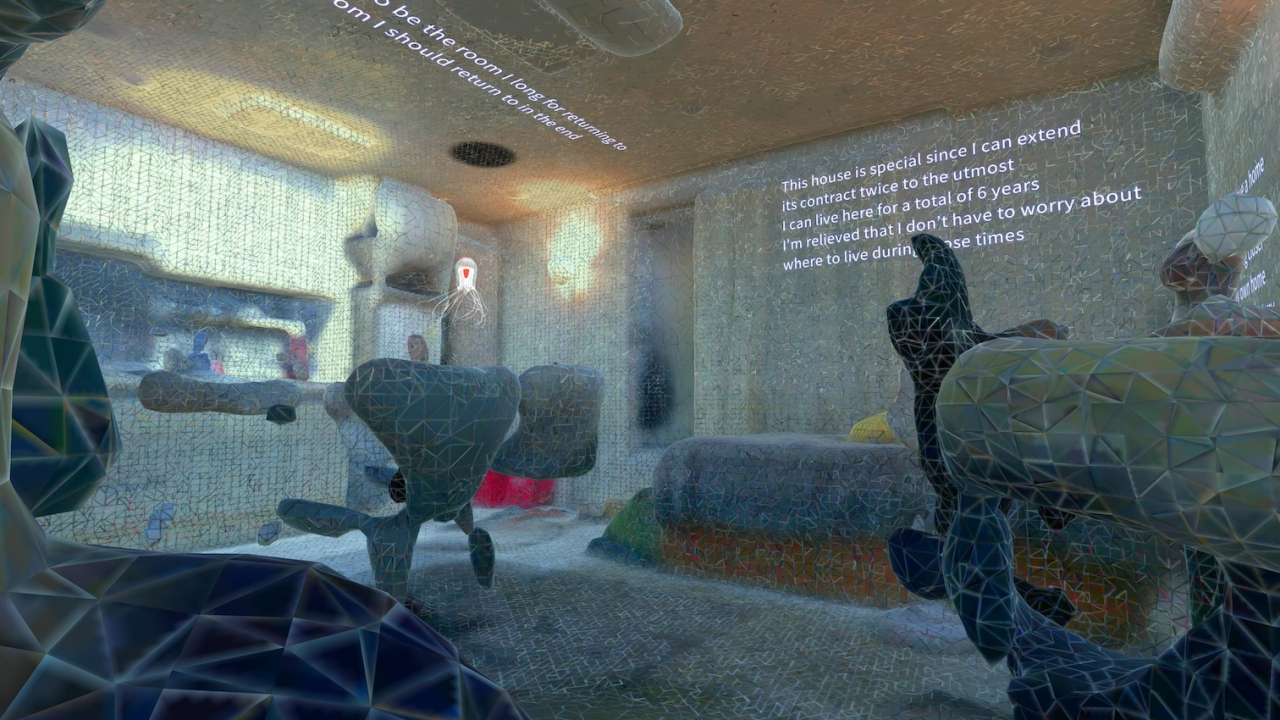

The fiction inside computer games,

inflated at the speed of spec escalation, now produces worlds mass-manufactured

at a one-to-one scale with Earth—vacuumed out as emptily as outer space, with

no need for cartographic reduction. These worlds grant agency or omnipotence

either in excess or in a void, streamed at resolutions higher than human vision

and powered by economies more volatile than global financial crises. Have we,

as users, failed to equip ourselves with imagination commensurate with the

processing capacity of these advanced machines, or with the ability to devise

arithmetic and rules equal to their might?

In any case, a rift has clearly

opened between the material capacities embedded in the devices that run games

and the immaterial potentials latent in the games’ arithmetic and rules. What,

then, becomes possible with games whose math and rules are simple enough not to

require computational delegation? Returning to the exhibition, the story

proceeds as follows:

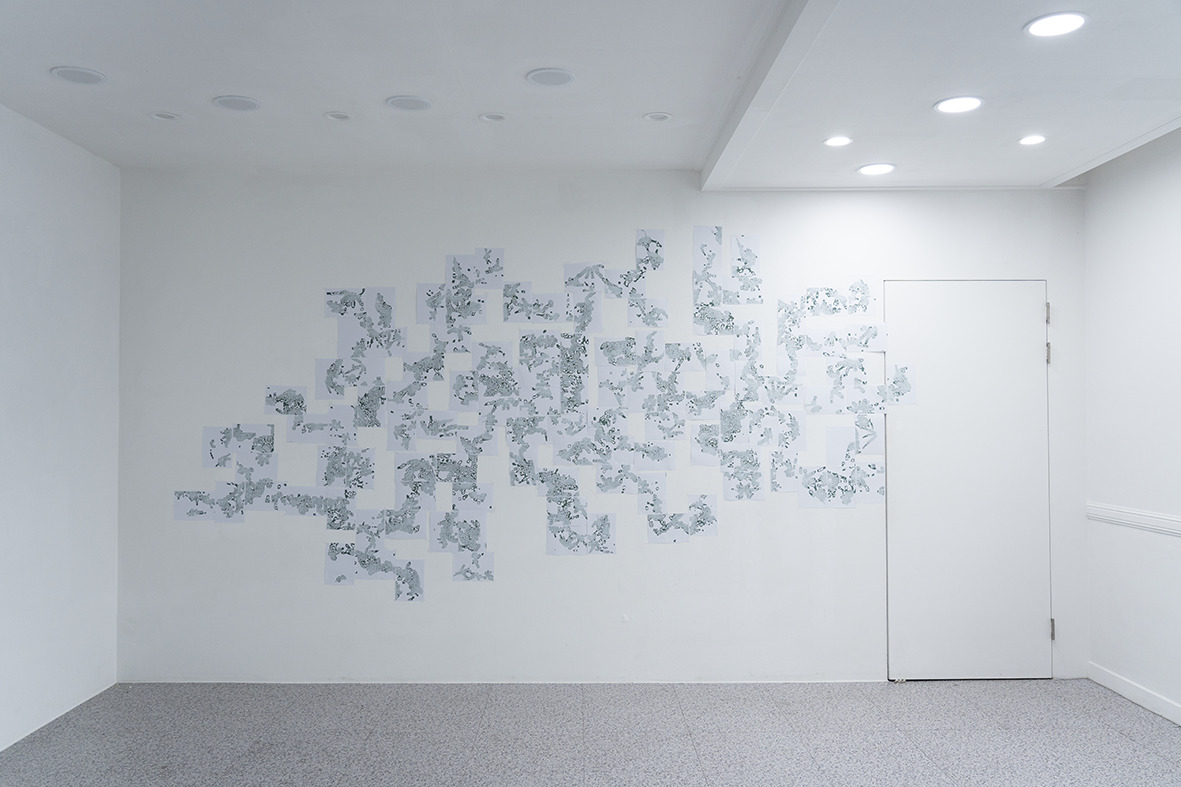

If

the hardware running a piece of software called Bugs of Nostalgia is

everything that composes the exhibition “Conversational Map for

Encounters,” then the map installed in the gallery functions as the

interface, and the apparatus that truly operates the software to produce

fiction is none other than the artists themselves. Not only because the artists

act as GMs within the exhibition—referring to the rulebook and conversing with

PLs (players) to literally run the game—but also because this work is as much

an interactive performance as it is a mechanical execution.

To make the game

convincingly “run,” the GM (artist) not only inputs and outputs sticker-like

symbols on the map interface, but also calculates dice rolls, spots the map

with light for emphasis, selects BGM appropriate to each situation, and

occasionally performs NPCs in a lifelike manner. In a modern computer such

arithmetic and rule-processing would be concealed; in “Conversational

Map for Encounters,” it is overtly exposed.

The gallery as a sandbox

functioning as a single stage, the GM (artist) as hardware exposed on and

offstage, and the map as an interface relaying the stage all make visible an

operation that constantly synchronizes reality and fiction. In other words, the

language that produces fictions worth willingly connecting to—and the labor

that operates them—are dragged out into reality rather than hidden behind

conveniently automated software.

Thus, the audience, at the PL layer, can

watch—and indeed join—the process by which the game Bugs of

Nostalgia runs, witnessing in real time how conversation and

action generate fiction in reality. Following this participation, a viewer who

was a PL finds themself smoothly logged into the fiction of “City P” as a PC

(player character)—with neither a computer to delegate computation nor an

avatar to delegate agency.