Since

the late 2010s, Jang Jinseung has been exploring certain questions through his

video and mixed media installation work: What does it mean for human beings

when images allude to “seeing” that no longer requires a human “seer”? What

happens in our world when data transcend their nonmaterial state and transform

into different objects that reconstruct human identity, consciousness, and even

imagination? (In other words, what kind of world does this reconstruction

create?) These questions recall the work of Trevor Paglen, who has recently

been actively experimenting with audio-visual recognition systems based on

computer perspectives and artificial intelligence, or Ed Atkins, who has used

computer graphic-synthesized moving actors in variations on the different

relationships that exist between the digital, the physical, and the

psychological.

To be sure, it is also possible to draw connections between

Jang’s artistic work and the ideas of the many digital media scholars and

philosophers of technology who can be invoked to explain the work undertaken by

Paglen and Atkins. The reason for this pedigree is not to speculate on or

critically evaluate the quality of Jang’s work in comparison to the work of

those other artists. I am simply stating this early on to establish how his

work engages with the various epistemological, existential, and cultural

questions that are searched for, and identified through, keywords such as

“post-internet” and “post-human.”

Face

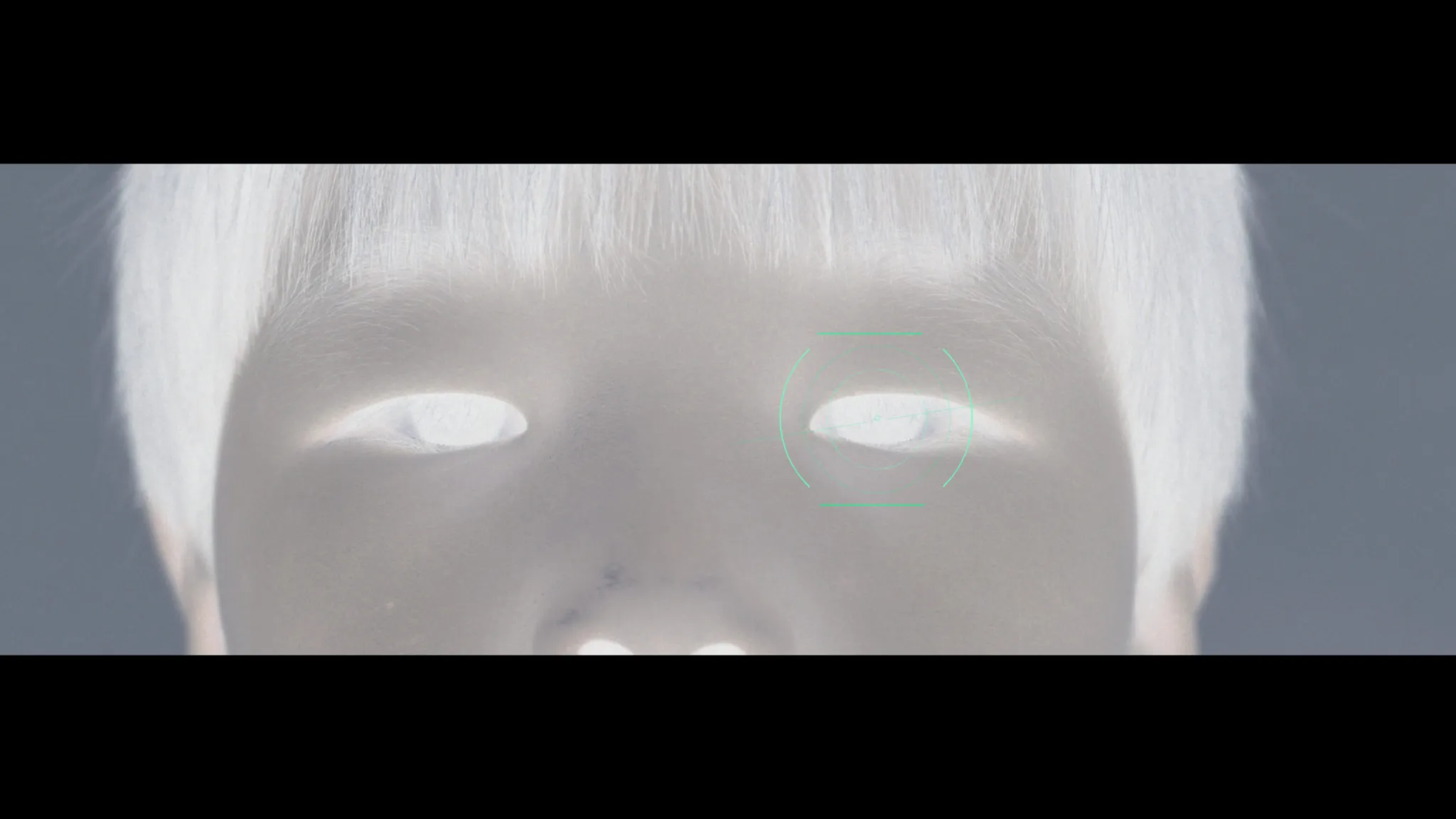

De-Perception (2017), Jang’s graduation project at Goldsmiths,

University of London, is a facial recognition algorithm system linked to Kinect

motion sensing and an oscilloscope. Human faces captured by the computer-linked

camera are first stored as black-and-white data, which is then converted into

pixel data and sound information through algorithm calculations. Converted once

again through the oscilloscope, that information is finally outputted as visual

patterns for the facial shapes. The system operation that ties together this

multi-stage conversion process “erases the individual physical identities of

different people and shows them in a way that maximizes the similarities common

to all human beings.”

The intended function of the operation is to

“symbolically delete the layers of discrimination and preconception through

which we view each other.” We can identify Jang’s critical stance by drawing

connections between this function and the work’s title. The “de-perception”

part signals that human perception is a product of socially based

“discrimination and preconception” that cannot be reduced to natural

capabilities, with the “de-” prefix referring to the removal of those same

discriminatory attitudes and preconceptions.

There

are two questions that this raises, or that could be raised in connection with

this. The first is the same question asked by figures such as Wendy Hui Kyong

Chun, Kate Crawford, and Hito Steyerl: Is it not the case that computer-based

image production and circulation systems combining algorithms with AI networks

are actually far from objective or neutral—that they both reflect and reinforce

societal discrimination and preconceptions in the construction, dissemination,

and operation of computer-based media, as we see in the examples of facial

recognition systems used for airport security and police profiling?[1]

The second question concerns how human beings and the world

are actually seen by these systems from which human perceptions have been

removed, and how the world looks when these systems have been visualized. Some

of Jang’s works clearly focus on investigating the second question. In (Miss)

Understood (2017), a documentation video showing the testing and

operating of Face De-Perception, the viewer’s

perspective is identical to that of the facial recognition system.

In addition

to seeing the participants interacting in different ways with the system, the

viewer also experiences changes in abstract line patterns and sounds produced

in real time through the automatic recognition and conversion of their faces,

along with changes in the numerically converted data values. As this shows, a

major focus of exploration in Jang’s work has to do with the operations of

devices that perceive human beings and the world yet compute different images

of them—what Paglen refers to as “seeing machines”—and the visualization of the

data computed by these machines or their conversion into various physical

objects.

These

explorations broaden into the realm of the interfaces and infrastructure that

constitute today’s automated societies. Before Termination,

the second episode of his omnibus film ‘Decennium’ Series (2020)

produced in collaboration with artist Lee Eunhee, documents the process as a

former taxi driver and current driver of the self-driving taxi “I-Limo” gets in

a taxi alone to go home. From the perspective of the driver who is wearing goggles,

the viewer experiences the I-Limo’s real-time updates of road and distance

information up until the moment just before an accident.

Jang’s focus with this

film is not simply to show the inherent dangers of self-driving systems or

imagine an agent subjugated by platform labor. He is using the embodied perceptions

of virtual reality to communicate the post-human emptiness and unpredictability

of the informatized world that emerges when the public realm of road signaling

systems is supplanted by privatized automation systems.

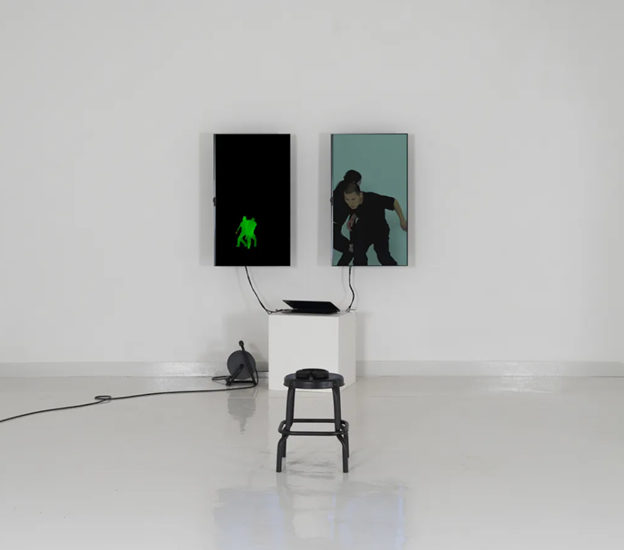

In Data

Circulation System (2020), Jang presents the viewer with

perceptions at the infrastructure level as data are circulated and stored,

including Data Cabinet which visualizes facial

recognition data from Face De-Perception and a

self-operating robot that gathers data. Just as the driver manipulating

self-driving system data in Before Termination becomes

the subject of the data experience, the viewer in this system is both a

provider of data (object) and a subject watching themselves being converted

into data.

In

these ways, Jang Jinseung has explored the workings of automated “seeing

machines” that essentially do not require human beings, and the perspectives

and images that they give rise to. In the process, he interrogates the ways in

which the data circulated through these machines’ connections neutralize or

restructure the distinction between subject and object, or between physical and

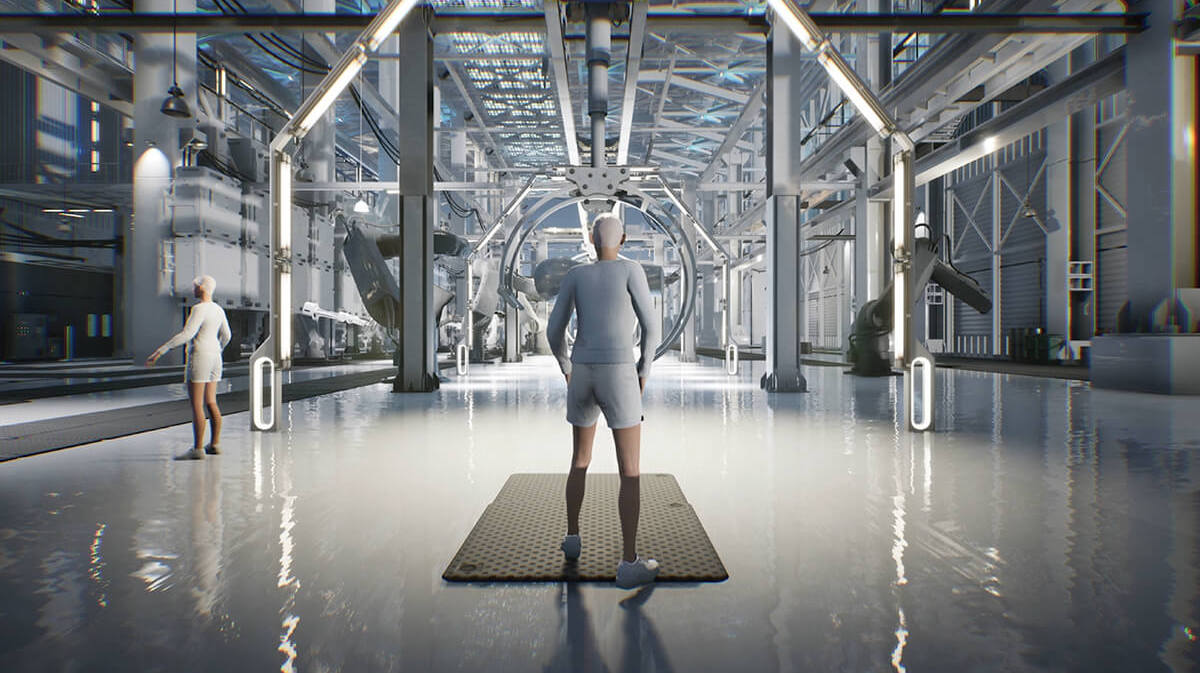

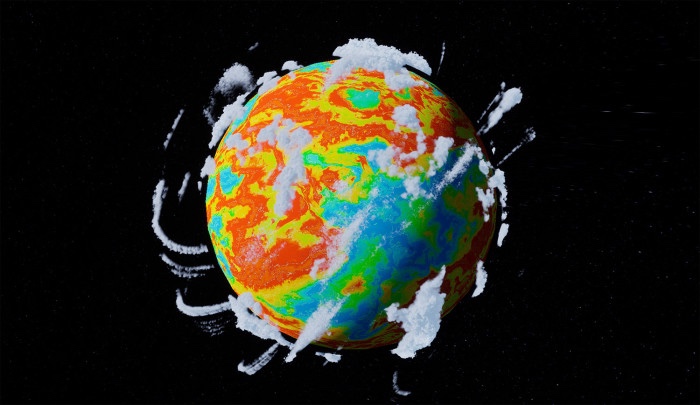

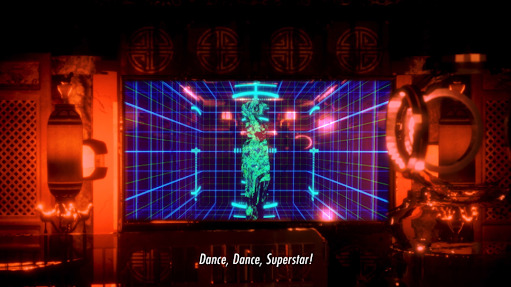

virtual space. In Deluded Reality (2021), he

offers an extreme adventure of the meta-human created in a world where simulations

form the basis of nature and memory.

The character here establishes their

bearings as they sense the smells and salt of the sea and the cold polar

temperatures, passing by a factory that mass-produces similar meta-humans as

they trace back the origins of their own creation. The self-exploration of this

virtual human swimming against the rules of physical time and space unfolds in

a way that blurs the traditional boundaries between humans and nature, but all

the spaces in which that search takes place are part of a world rendered in the

same 3D computer graphics often used in video games and machinima.

While

the theme of Deluded Reality is a world rendered completely virtual,

one in which the boundaries between the real and virtual have been

fundamentally erased, we may also raise the question of whether the physical

and virtual worlds simply exist in a blended state, or whether some gap exists

between the two. This is the question explored in Jang’s most recent work Virtual

Chronotope (2022). A video essay reflecting on the concept of

the “virtual particle” in physics, it has the artist using virtual camera

techniques—modeling a panoramic form of visual tracking—to connect

black-and-white images of an actual city with monochrome versions of those

images and monochrome graphic images that recall those recorded by an infrared

camera.

The continuity in perspective corresponds to the layering of real and

virtual space, yet it also draws attention to the gap between the real and

graphic images. Moreover, this gap denotes a “free space” that emerges from the

lack of correspondence between the real and virtual space—what the narration

describes as a “space containing multiple layers and energies.” The work does

not share what these layers and energies represent or what potential they

harbor. But they are definitely questions that Jang Jinseung will continue to

explore through CGI and digital visualization in his future work.

[1] For more on these questions, see Wendy Hui Kyong

Chun, Discriminating Data: Correlation, Neighborhoods, and the New

Politics of Recognition (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021); Kate

Crawford, Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of

Artificial Intelligence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021); Hito

Steyerl and Trevor Paglen, “The Autonomy of Images, or We Always Knew Images

Can Kill, But Now Their Fingers Are on the Triggers,” in Hito Steyerl: I Will

Survive, eds. Florian Ebner et al. (Leipzig, Germany: Spector Books,

2021), 239–256.