Jinseung

Jang’s interest in the body and body data begins with Data,

Polaroids, which he first created in 2012. This work consists of

Polaroid photos of people with eyes closed, various skin colors, skeleton,

hairstyles, and clothes that can help you guess gender, age, and race. The

different appearances of the individuals in the photos arranged in a grid forma

strange contrast with the blurry colors unique to Polaroid photos and the

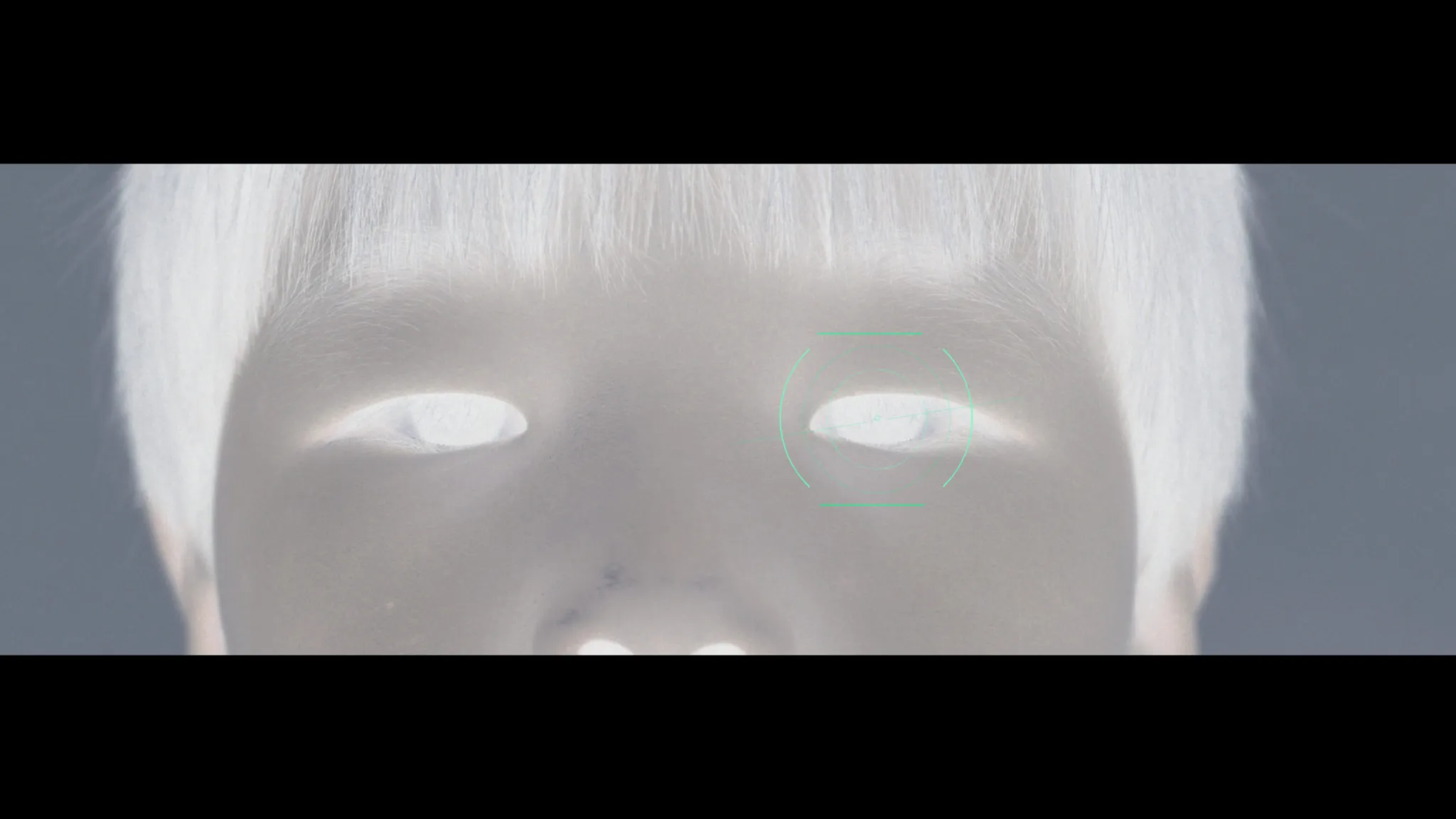

uniform square frame. The critical view that started here leads to Face

De-Perception in 2017, which was also the graduation work of

Jinseung Jang.

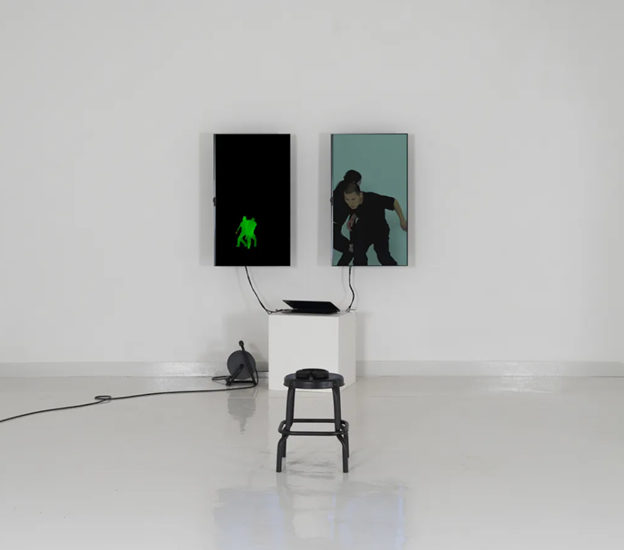

Above the monitor is a Kinect that detects a moving body with a

3D sensor and converts it into data, and below it is an oscilloscope that

converts the signal into a waveform and displays it. In front of these

mechanical devices connected by complex wires, there is a sub-woofer that

reproduces sound in the low-pitched range. When the audience stands in front of

it, the position of the eyes, nose, and mouth of the face detected by the

Kinect sensor is patterned into dots and lines on the monitor. A corresponding

sound sounds. About this work, the author says:“

It

was produced with the intention of symbolically deleting any layer of

discrimination and prejudice that each individual sees each other by erasing

the individual physical identity of different people and maximizing the

similarity of humanity that all humans have… I think it is possible to break

the chain of discrimination by proposing a new way of looking at each other

through objective data while locating a third medium called a machine in the

gap of how each other perceives each other.”

In

fact, even before we know what kind of person a man or a woman is, we predefine

our attitude or mindset toward him/her from the ‘physical identity’ of the

other person’s body we encounter, in no small part due to deep rooted

religious, cultural, and political prejudices. Jinseung Jang seems to have

thought like this. If our perception of the body of others is tainted with such

a ‘layer of discrimination and prejudice’, the body data obtained by

‘de-perception’ of this ‘human perception’ can provide the possibility of

‘breaking the circle of discrimination’. From this point of view, the mechanism

of Face De-Perception, which converts the audience’s face

into oscilloscope waveforms and sounds, is a tool to neutralize the natural

materiality of the human body, like the Polaroid photos of Data,

Polaroids with uniform frames and colors.

However,

the datafication of the body does not happen only in this direction. In many

cases, body data is used in the opposite direction, violently pulling the body

out of its protective web of anonymity. For example, using facial recognition

technology, the Chinese government can identify and arrest wanted criminals in

a crowd, or identify traffic violations such as jaywalking or not wearing

seatbelts, and impose fines. This is the reverse application of the same

technique used in Face De-Perception to ‘erase the

physical identity of an individual body’.

Face detection technology that

detects an individual’s face pattern can always be linked with Face

Recognition, which identifies the owner of the face based on the data. At will,

the technology could be used to single out from a crowd people with certain

physical characteristics of a certain race or gender, as well as people with

certain facial expressions, gestures, or even certain words. (It has already

been exposed that the Chinese government intends to use this technology for its

minority surveillance system.)

Datafication

of the body is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it makes our lives

amazingly convenient. Instead of entering cumbersome passwords, we open our

smartphones with facial data and make user authentication instead of banking

transactions. A smart watch helps you manage your health by measuring your

steps, exercise amount, breathing and pulse rate and providing feedback. (Hwang

Heechan’s black underwear, which drew attention in the Korea-Portuguese World

Cup match, was also a body data-generating device that checked the player’s

condition by measuring the distance traveled, speed, heart rate, and

acceleration.) It has been a long time since mechanical devices that measure

and inform the state have helped patients in hospital maintain their lives.

In

this way, the greater the possibility of access to the information contained in

our body, the greater the possibility of using body data for the health and

well-being of the body. In fact, The First Kid, a short

video from the Decennium Series produced with Lee Eunhee in 2020, imagines such

a possibility. Here, a ‘child aptitude test’ system appears that measures the

child’s aptitude and ability in detail with the data obtained by scanning the

body of a 7-year-old child to the level of DNA, and suggests a suitable

curriculum and job.

Thinking of people who spend time and energy wandering

between temporary curiosity, coincidence, and exaggerated (delusional)

aspirations until they find a major and job that suits their aptitude and

ability, a system that propose it, based on in-depth data of each person’s

body, may give birth to a new humanity, as Charles Fourier dreamed in the early

19th century. However, in The First Kid, the child who

undergoes the aptitude test is somewhat anxious and cramped, and the future

occupational aptitude presented as a result of the measurement – an artist! –

doesn’t seem to make the child happy either.

Since

then, instead of the tech-utopian prospect of Face De-Perception,

which suggests that technology can overcome the bias of human perception, on

the basis of contrasting human with technology Jinseung Jang seems to have

changed his interest to the ambiguous and uneasy but certain relationship

between humans and machines. And it tends to be moving toward accepting

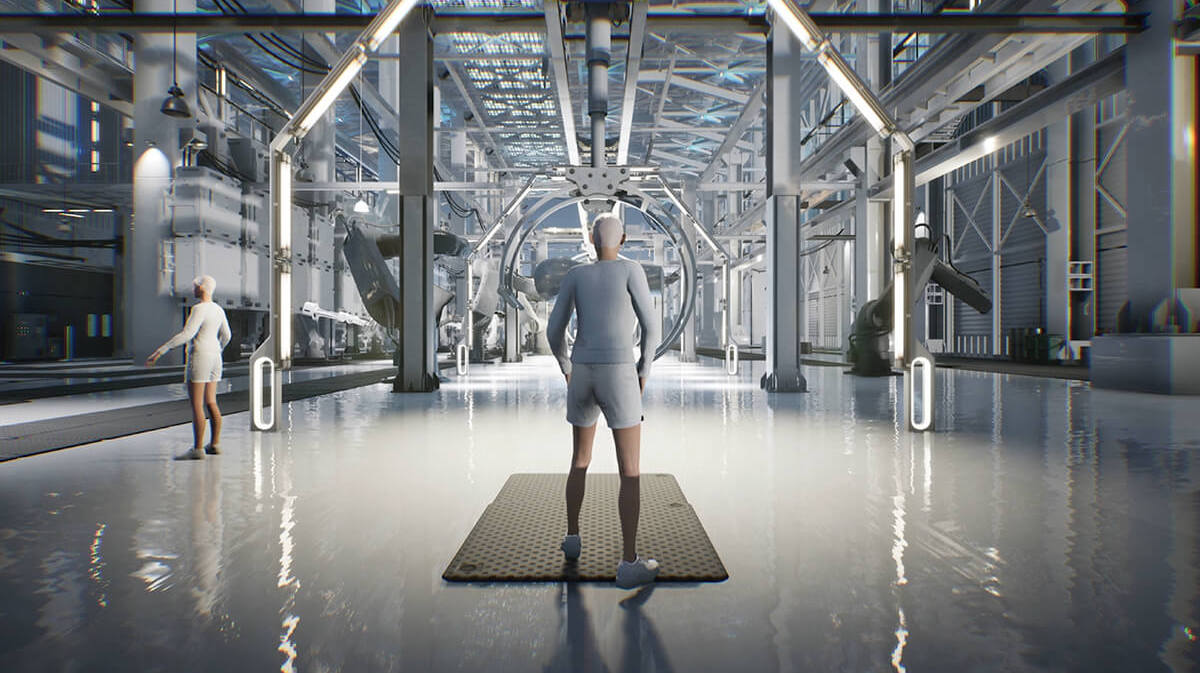

intimacy. The humanoids in Deluded Reality (2022)

are confused while asking themselves why they exist in a factory where bots identical

to themselves are manufactured, so do the humanoids in Data

Monument (2022), either, who have bodies indistinguishable from

humans. The humanoid Agent K., who appears in L.A.P.S.E (2022),

expresses the meaninglessness of his existence in a museum that no one visits

and no one pays attention to, with his mission to ‘protect from everything’,

but he is not very concerned about it.

Datenprotokoll (2022),

which was submitted to the “The Breath of Fresh” exhibition, is noteworthy as a

work that shows the artist’s changed perspective on humans and machines. The

technique used here is essentially the same as that used in Face

De-Perception. The difference is that instead of the audience

accidentally passing by the device, two performers intensively move their

bodies in front of the Kinect. Azure Kinect, takes the head, neck, right and

left hands, knees, collarbones, shoulders, elbows, hips, and feet as points and

converts the movements into position data for each body point. As in Face

De-Perception, the artist converts this data into sound with a

specific frequency and beat. However, by introducing the movement of the

performer, a new aspect is highlighted that was not well revealed in the

previous work; the compatibility of man and machine.

When

you see and hear the sound that changes according to the performer’s movements,

it seems to be similar to the performance of Theremin at first glance. But

there is a fundamental difference from it. Unlike Theremin, which makes sounds

by interfering with electromagnetic fields with your hands, it is because there

are 16 body points that generate sounds here. Theremin’s sound can be

controlled entirely by hand. So, we call the person who makes sound by moving

their hands in front of it a ‘player’. However, can the performers who generate

data by moving their bodies in Datenprotokoll be

called ‘players’ of the resulting sound?

Even a professional dancer cannot

independently control the movements of the hands and elbows, shoulders and

collarbones, knees and feet, and right and left hips. Therefore, the sound we

hear here is a combination of the movements of the hands, feet, head, etc.,

which the performer voluntarily controls, and the nonvolitional movements of

other body points that are not. Here, the performer’s body does not ‘play’, but

only creates data. The scene that shows a moving performer and the data values

of each body point that changes in real time according to his movement

illustrates this.

In

body movements that are converted into data, we cannot distinguish between

human volitional and non-volitional actions. In fact, in the movement of the

human body, occurs a feedback process between the kinesthetic sensory system

and the nervous system, which we cannot consciously control, Norbert Weiner

said. “Suppose that I pick up a lead pencil. To do this, I have to move certain

muscles. However, for all of us but a few expert anatomists, we do not know

what these muscles are; and even among the anatomists, there are a few, if any,

who can perform the act by a conscious willing in succession of the contraction

of each muscle concerned.

On the contrary, what we will is to pic the pencil

up. Once we have determined on this, our motion proceeds in such a way that we

may say roughly that the amount by which the pencil is not yet picked up is

decreased at each stage. This part of the action is not in full consciousness.

To perform an action in such a manner, there must be a report to the nervous

system, conscious or unconscious, of the amount by which we have failed to pick

up the pencil at each instant. If we have our eyes on the pencil, this report

may be visual, at least in part, but it is more generally kinesthetic,

or…proprioceptive.”

What

Wiener pays attention to is the action actually taken after the decision to

lift the pencil. What the muscle movement controls is a feedback process

between the kinesthetic sense and the nervous system that detects the amount

the pencil has yet to lift. Here, “its most characteristic activities are

explicable only as circular processes, emerging from the nervous system into

the muslces, and re-entering the nervous system through the sense organs.”

The

movement of the human body has an inherent information exchange process between

the kinesthetic sense and the nervous system, which is not conscious to humans

but can be mathematically calculated and predicted. What was born from this was

“the entire field of control and communication theory, whether in the machines

or in the animals”, that is cybernetics. The principles of cybernetics machines

that operate on their own without human intervention, from robot vacuum

cleaners to self-driving cars, also work in the same way as the human body

moves. So, Norbert Wiener was able to develop an anti-aircraft missile system

that predicted the path of an enemy plane by calculating not only the speed and

position of the flying plane, but also the pilot’s evasive maneuver to avoid

the missile. The first step in all of this is capturing seemingly irregular and

arbitrary patterns of movement and turning them into computable data.

The

converting the human body into data contains the germs of the Humanoid that

moves like humans. It is no coincidence that both of them appear in Jinseung

Jang’s work. Jang’s humanoid, with its fragmented skeleton, clearly visible

inside the torso, is seemingly different from the human body. However, the

humanoid who accepts the “how human’s society works” (L.A.P.S.E)

where all things “are actually there for their duty and reasons” does not seem

very different from us humans who live like that.