Do

highly advanced extraterrestrials exist? Can Earth’s inhabitants migrate to

other habitable planets or colonise alien planets? What was once a distant

science fiction fantasy depicted in movies has now become a tangible and

realistic task centered on the conquest of space. In Stanley Kubrick’s film

2001: A Space Odyssey, released 55 years ago, astronauts heading to Jupiter

encounter a mysterious giant black monolith. Though its purpose is unclear, the

AI accompanying them, HAL, attacks the humans.

The enigmatic black monolith in

the film, referred to as a “monolith,” has since come to symbolise either a

tool of aliens or a highly advanced computer. If we were to identify a monolith

in 2023, it might take the form of globally iconic obelisks or cutting-edge

quantum computers that are redefining U.S.–China competition with their immense

power and destructive potential. The monolith represents not only a mysterious

symbol of human power but also the idea of a vast, singular organisation—a

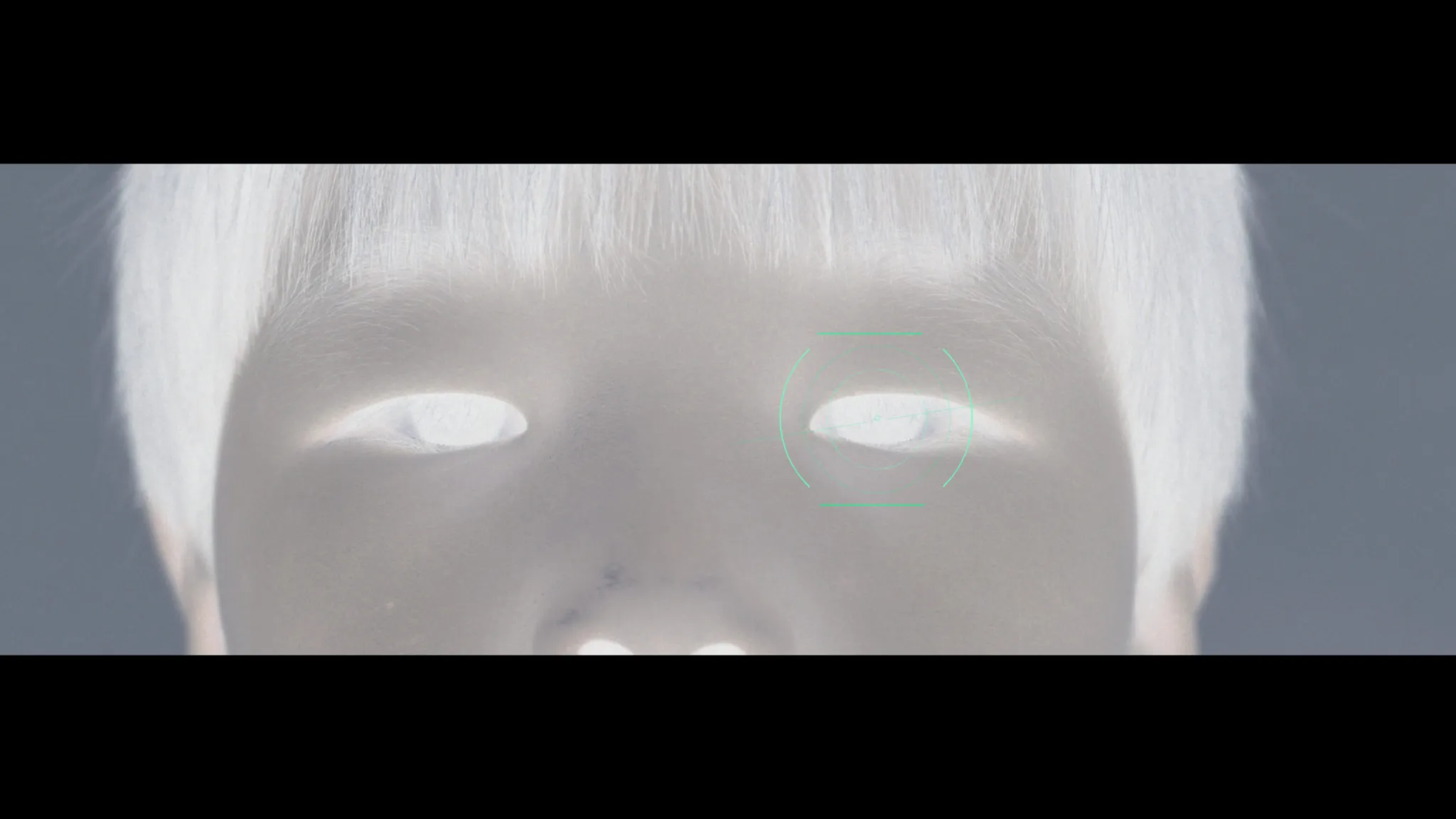

single block of stone. Just as the malfunctioning (or possibly self-evolving)

AI in the film attacked humans, today’s algorithms and AI systems reveal a

constant potential for threats: they invade personal information, infringe on

physical autonomy, control, and even subordinate humanity, possibly leading to

ultimate destruction.

While we rely on high-tech advancements like human

cloning, Neuralink, and autonomous robots for convenience, we are

simultaneously confronted with the fundamental harms they introduce. The increasing

emphasis on binary thinking and universal standards—pursuing only national or

corporate interests and efficiency—amplifies concerns about societal and

capitalist power structures.

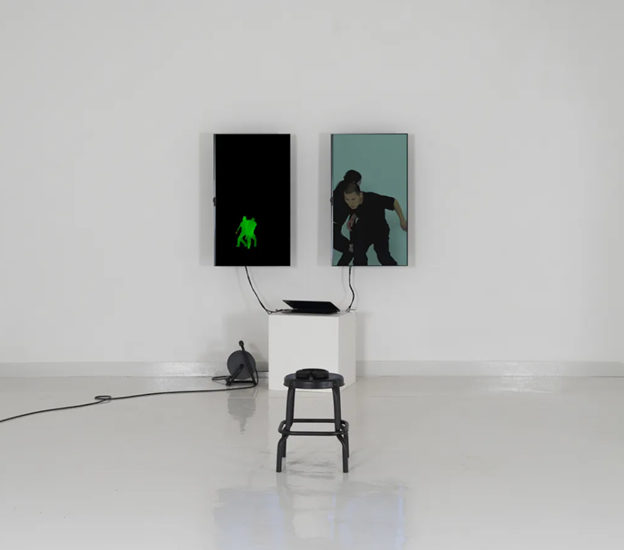

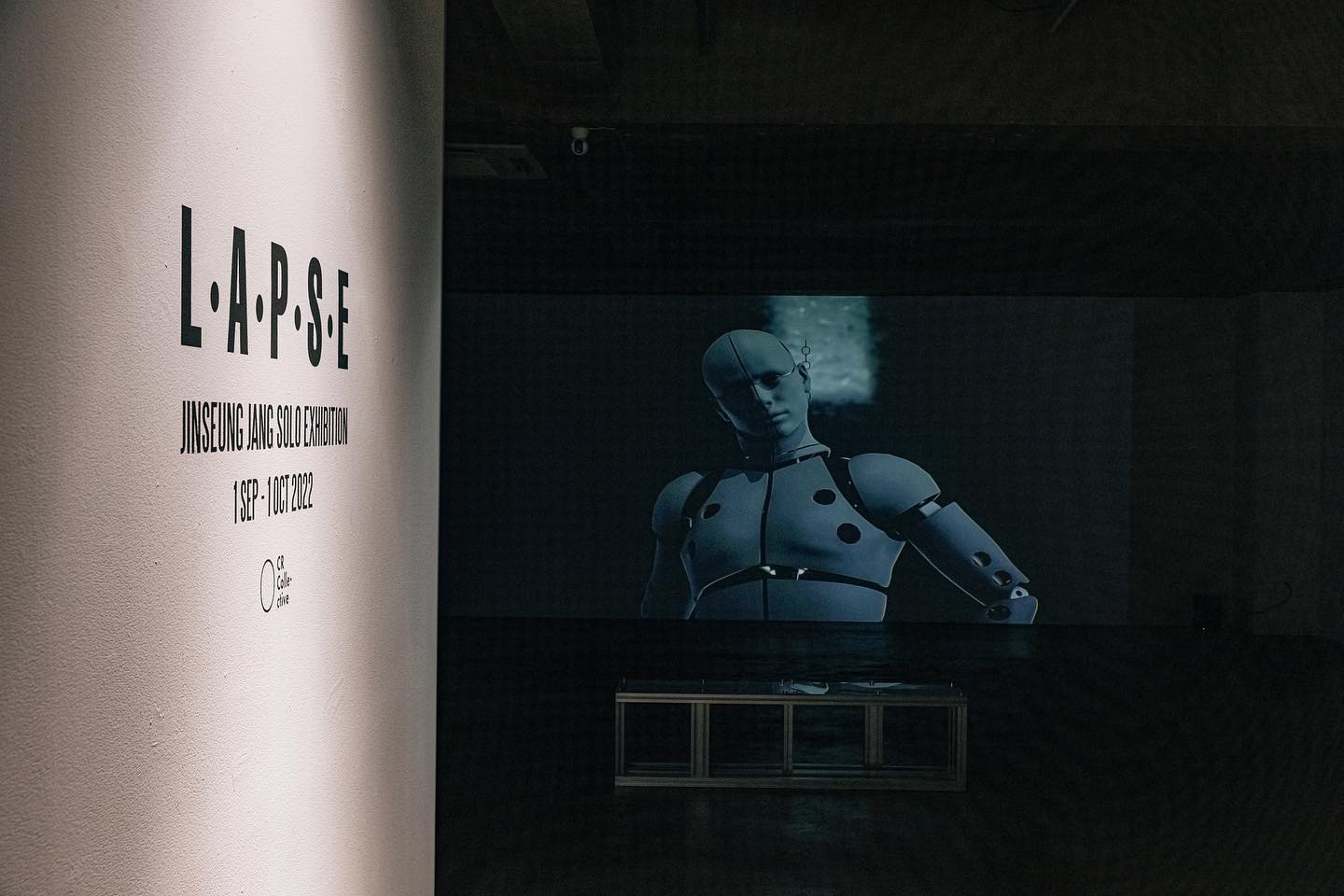

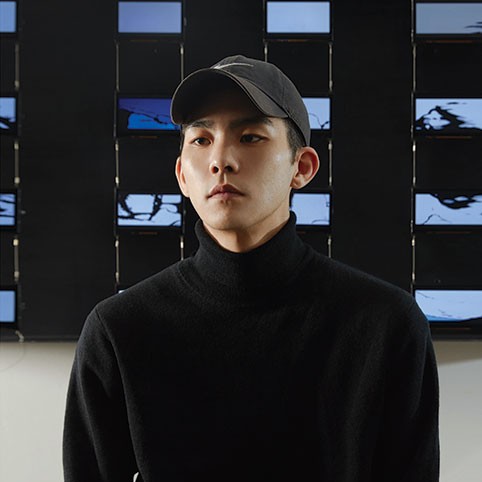

In

2023, artist Jang Jinseung’s 《Data Monolith》 addresses these pressing “discourses on future humanity.” On the

artist’s website (http://jinseungjang.com/data-monolith/), information about

his past works, designs, exhibitions, and performances is archived alongside

the Data Monolith project. The site, featuring a pulsating Data Monolith logo,

is divided into four sections (Monolith I, II, III, IV). Clicking on the

respective icons—buildings, white triangles, emptiness, and semiconductor

chips—teleports users (and their avatars) to specific locations.

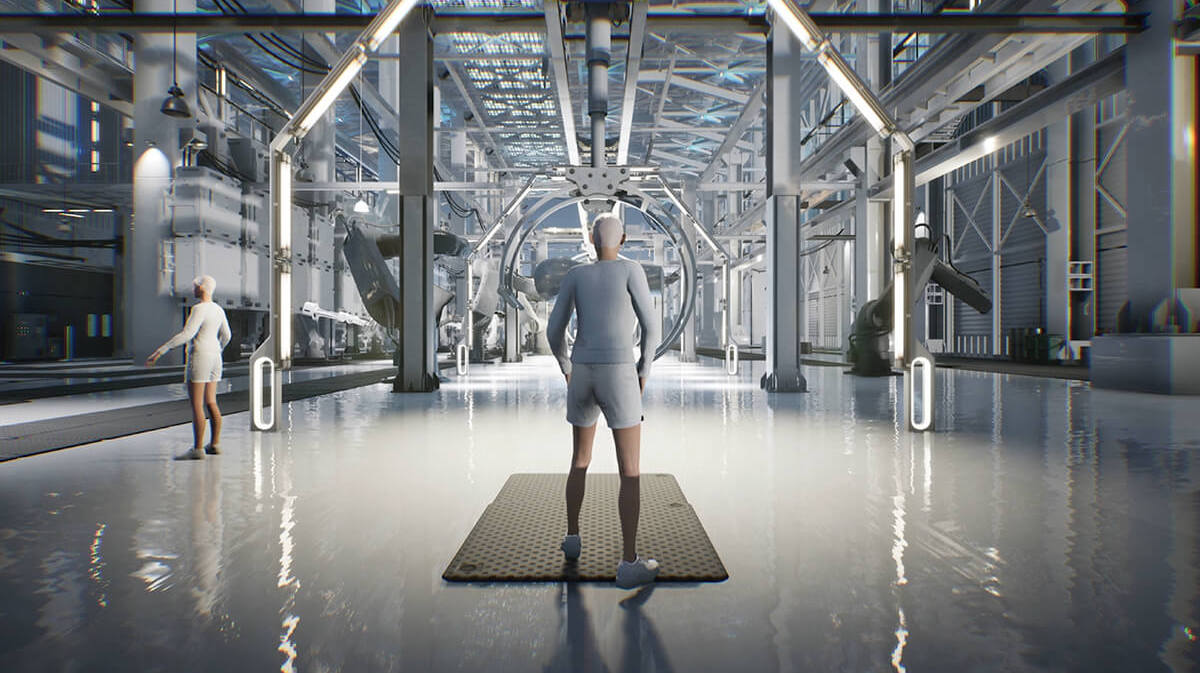

Monolith I

leads to the location of an open seminar, where seminar content and documents

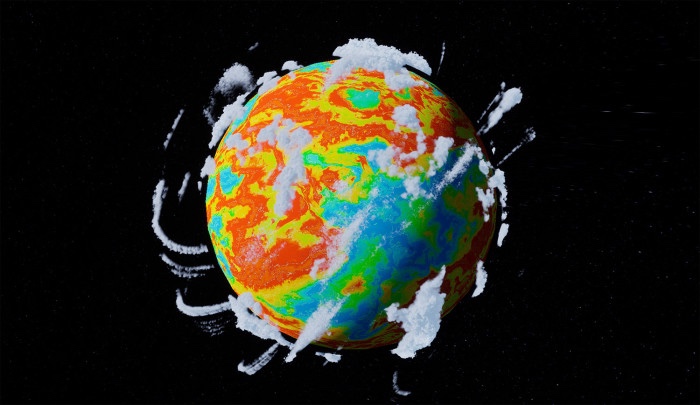

are erected like a monolith. Monolith II transports users past a machine-filled

space to an icy, snow-covered surface reminiscent of Earth’s ice age. Monolith

III takes users to a primordial, black void shaped like a rectangular ring.

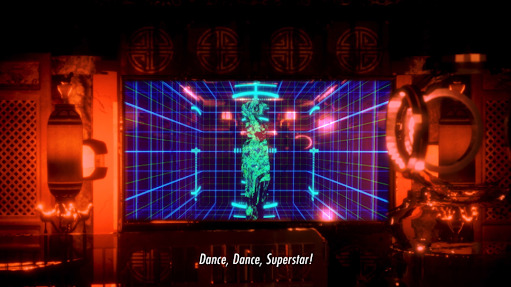

Monolith IV moves them into a space filled with massive machines resembling an

alternative form of humanity. Scrolling further down the webpage reveals

content divided into ten chapters, such as “Data,” “Image Data,” “Text Data,”

“Data from Computers, Smartphones, and the Internet,” and others. The text

progresses to “Big Data,” “Data and Politics,” “Data of Artificial Life,”

“Quantum Computers and Simulation Data,” “Human Self-Destruction,” and

concludes with “The Resurrection of the Image” and the Data Monolith.

It

documents this progression in a uniform format, akin to recording divine acts,

making the website both a designed archive of Jang Jinseung’s work and a

monolith itself. Unlike Mioon’s Art Solaris (2016–2020),

which tackled the taboo topic of “cartels in the art world” using big data,

Jang Jinseung’s Data Monolith explores the structures and conditions of data

discourse. Beyond relational aesthetics, it suggests speculative thinking and

interpretation through the concept of a “one-to-many transversing

multiplicity.”

Reflecting

current trends, 《Data Monolith》

adopts the format of an online exhibition. Instead of

traditional showcases, workshops and discussions were conducted with

participants and avatars on the web page and the metaverse platform Spatial.

The open seminar, themed around “contemporary data ontology and data

phenomenology,” featured contributions from writers and researchers. The

resulting process—culminating in an analog monolith print—tackled contemporary

debates on topics like data, multiplicity and sensation, and the universality

and taboos of science. Rather than concluding optimistically or

pessimistically, it revealed societal problems hidden beneath an open-ended

narrative.

Through collaborative discussions, the exhibition format reflected a

respect for individual opinions while reinforcing objectivity through public

debate. It also sought to counter criticisms of Jang’s work as overly complex

and opaque, presenting an alternative approach. This can be seen as the

artist’s attempt to navigate and adapt to the evolving language of art

exhibitions. Jang Jinseung expressed concerns during the Data Monolith

discussions: “I often feel this project is difficult because it doesn’t offer

clear answers. It’s challenging to portray the future concretely, nor do I aim

to map out a programmatic blueprint. What concerns me is how to navigate

through the broader macro-context, what role the individual (artist) plays, and

how far our (imagination and) senses can extend through personal devices like

smartphones.”

Professor

Lee Kwangsuk’s contribution highlighted the historical evolution of “data”

terminology in Korea, covering issues like social dynamics, economic concerns,

and the trajectory of data-driven capitalism. Distinguishing between weak

intelligence (AI) and artificial general intelligence (AGI), Lee forecasted a

bleak future with AGI and proposed balancing human-machine relations while

addressing the opportunities and problems of the emerging data-driven society.

However, even with advanced technology, unresolved issues such as manufacturing

costs and social inequalities persist. Jang Jinseung’s Data Monolith is a

reflection of his ongoing artistic exploration of the relationship between new

material and immaterial technologies and humanity, offering questions and

knowledge to escape societal constraints. It aims to dismantle life patterns

shaped by algorithms and AI, posing alternative inquiries into human freedom.

In doing so, Jang’s work continues to evolve.