In

recent years, the keyword “science and technology” has been especially hot in

the art world. Although the field has steadily discussed science and technology

since the 21st century, the online era—accelerated by COVID-19—has sped up

those discourses as well. And many artists do not simply embrace the current

situation in which cutting-edge technologies roll in like waves. It is perhaps

an attempt to self-correct our structures of consciousness that fall behind as

technology advances rapidly.

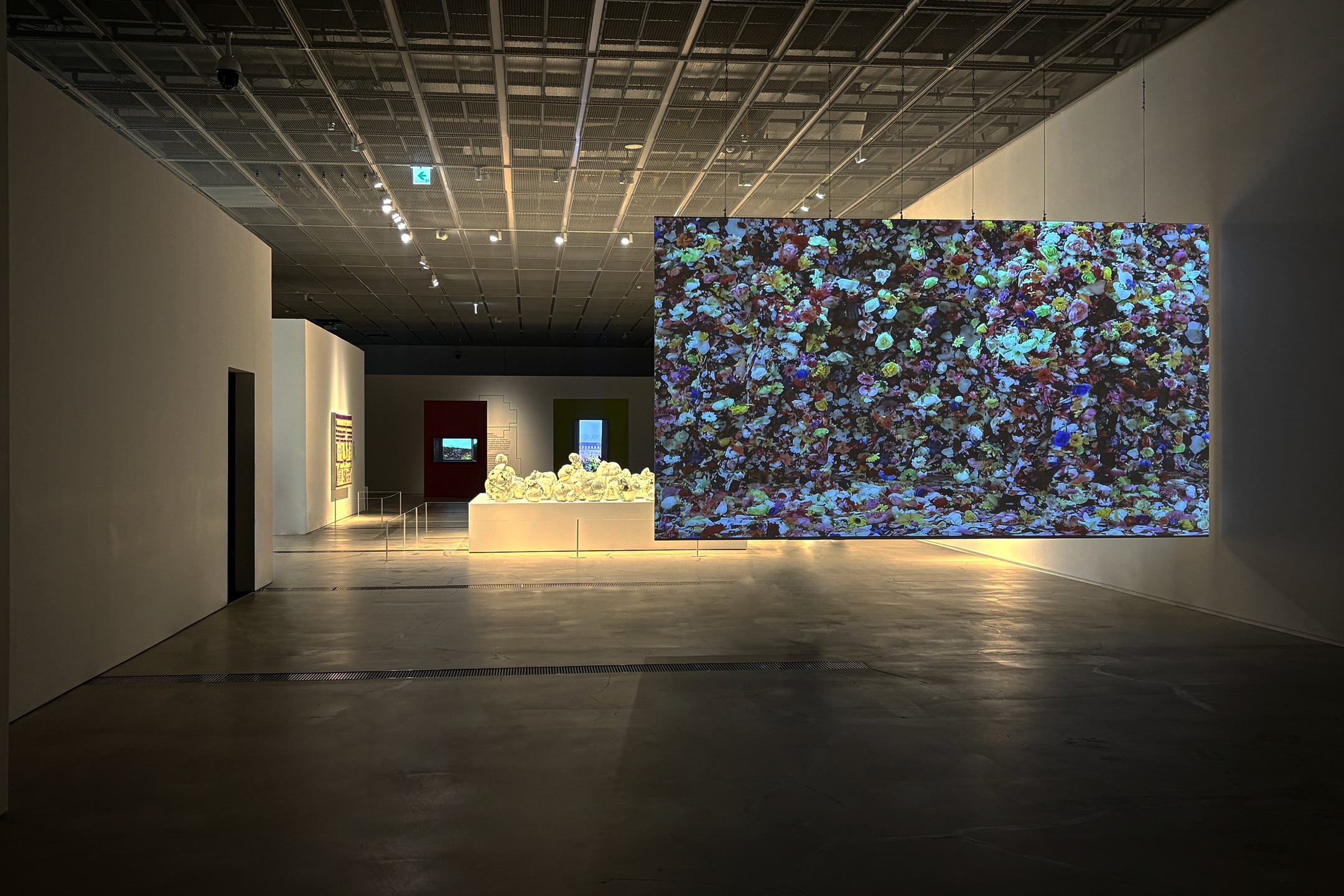

《Virtual Station》, currently on view at

Haenghwatang—a former public bath reborn as a multi-arts cultural

space—likewise focuses on the changes brought about by technological

development. Curated by Artistic Director Kim Sung-hee, the project features

Kim Jiseon, Kim Nahee, Rimini Protokoll & Thomas Melle, Helen Knowles, The

Blucky Production, Tiffany Lee, Seo Hyunseok, Yoon Taewoong, Lee Ungchul, Kim

Boyong, and Song Min Jung. Promoted as part of Arts Council Korea’s public-art

program, it runs through March 21.

Before

touring the exhibition rooms, let’s skim the preface:

“The

concepts that have become key topics in today’s art and critical thought—body,

time, space, city, community—were born in modernity. And with the rapid

development of technology, they undergo radical transformations. The ecological

system of thought and relations in which the subject had settled is destroyed,

and new networks of information replace the body and desire. The sense of time

and space is fragmented and exchanged for flattened information. Information is

capital. What can art do in the public sphere that has sunk beneath the

velocity of capital?

If

art has any role in the public sphere, perhaps it is to open a public plaza in

which such discussions can unfold vigorously, presenting diverse artists’

perspectives and agendas so as to offer starting points for seeing the world

more sharply and critically.

《Virtual Station》 looks

at technology from atop the ruins of modernity. It watches for seeds of new

sensibility behind the trajectories and textures of change set in motion by

technology, and behind myths that are no longer valid.”

—

Preface to 《Virtual Station》

In

short, 《Virtual Station》

revisits the influence of information technology cast over various critical

concepts born in modernity, and, through art, seeks to provide an occasion to

closely observe social phenomena with a sharp gaze. The project appears in

diverse forms—video works, performances, sharing sessions, VR, and more—but

here I introduce three video works that can be viewed regularly at

Haenghwatang.

In

“Oil Storage,” Song Min Jung’s Wild Seed is

presented. Its protagonist is a man named Kim Ki-cheol, deprived of his body

and drifting like a ghost through the world. He is found on an island in China,

his fingers severed by a cutter. The police officer who informs his daughter of

the news is so indifferent—avoiding the repatriation of the body because it

would be cumbersome or snapping that it isn’t a voice-phishing scam—that his

attitude scarcely resembles that of someone delivering a death notice to the

bereaved.

As

the story proceeds to trace his death in tandem with the contents of a memo the

man left behind, voices of various nationalities appear. A Chinese woman who

worked with him says only that he was “a man who smelled like fish.” She

remarks that what the living say about the dead becomes ever more embellished

in the absence of the person concerned—as if it were a novel. And she adds that

if information about Kim Ki-cheol were to affect her own safety, she would make

no statement at all.

We

then hear the voice of a customer-service representative explaining how to

handle the information left on the deceased’s social-media account. For an

additional fee, she says, Kim’s account can be converted to a memorial account

to preserve its data. The daughter replies that she will think about it and

call back. But when the representative phones again after some time, she states

that, for unknown reasons, the data has been lost and cannot be restored. In

the end, Kim Ki-cheol’s information is deleted.

In

other words, Kim Ki-cheol is a figure whose body has been taken by information

manipulation. In this world he is neither wholly dead nor alive. The only means

by which he could be remembered—information—has been completely erased online,

and those who had relationships with him in life refuse to testify about him.

This chain of events makes us feel viscerally the threat that information can

pose. Although the work takes the form of a “thriller drama,” its essential

meaning differs little from our reality.

For

the sake of convenience, we hand our information over to others with ease. But

convenience always requires risk. We live in a world where a public-certificate

number and a password can prove my existence on the internet; if that

information falls into someone else’s hands, anyone can impersonate me. In this

way, we live in an era where a small minority who monopolize information power

can control our daily lives at will. In an age when intangible information

proves who we are more effectively than physical substance, can we look at the

development of information technology in a purely positive light?

(…)

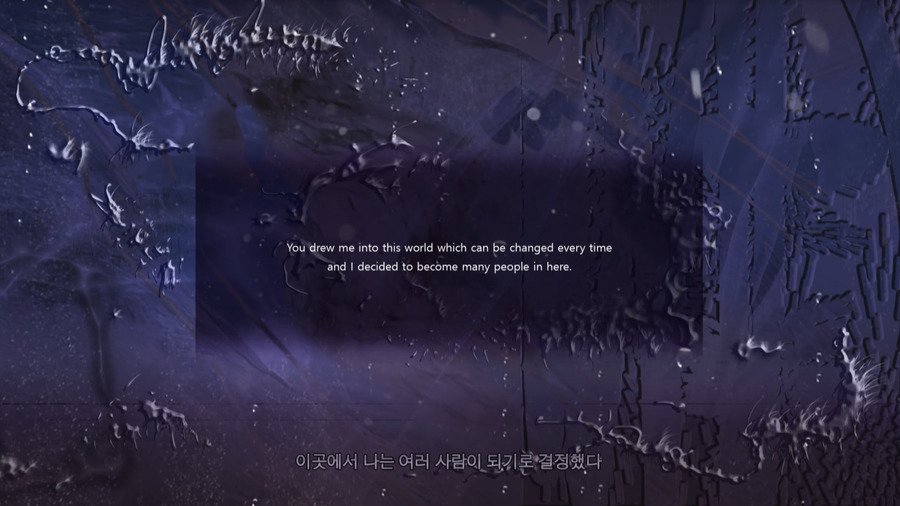

Today,

as immaterial data comes to govern our everyday lives, the entity facing the

greatest crisis may be our bodies. As online communication replaces physical

communion, our synesthesia will either grow dull or, conversely,

hypersensitive. At this threshold, contemporary artists sharpen their own

senses to respond, prompting viewers to be keenly responsive to the current

situation.