“Right,

there are two stages.

One is, of course, the stage on which forms are shown,

and the other—what should we call it?—

the stage that steps back a bit into the invisible.”¹

Looking

up at the five beings (entities) suspended from the ceiling, several feelings

and images seep in at once. One even senses they lean closer to death than to

life. They are bodies and yet not bodies, cycling between buoyant motion and

stillness. If the body were defined as the vessel that contains a soul, these

are mere mimetic shells. Between the kinetic objects that recall segmented

bodies and the orchestration of light and sound that envelops and penetrates

the entire space, I offer a few notes toward reading Hkason’s performance Mirror

and Cloak(2024).

Curtain and membrane

For Hkason—who studied fashion in addition to media art—the body would have

been a constant object of scrutiny in pattern making and draping. In that

sense, “mirror” and “cloak” can be inferred to function both as devices that

reveal and that cover the body. In fact, no literal mirror or cloak is found

anywhere in the performance space. What, then, must be—or be able to be—the

mirror, and what the cloak? The artist’s remark that they were “interested in

making the invisible appear (…) and, while working in series on that flow,

artificially placed obstructing membranes on the plane” connects directly

to Mirror and Cloak. The intention to have the audience

“wear” the space as a whole already forms, in itself, multilayered membranes

and cloaks.

A mediating body

The skeletal framework that organizes the body does not speak. Look closely and

you find only small internal motors enabling all movement. None of the five

entities rises upright from the floor; all hang down from above. From the

outset, Hkason avoids the labor of approximating materials that must be, or

plausibly resemble, a body. Aside from earlier works like Ascending,

Preceding, and Following(2022) and Relaxation and

Expansion(2022), which directly used hand-rehabilitation devices or

elements such as legs, hands, and shoes, the effort to “look like” a real body

seems absent from the artist’s intent. Rather, the stance is closer to a

neutral state “of being none of these,”² between human and nonhuman. Hkason’s

objects sometimes take a wearable form intended for acts of donning—as in the

collaboration with Dew Kim, Armoured Evolver(2020/2021),

or in The in Between Gesture(2022)—yet more often exist

fully as autonomous things, experimenting at the boundary where body and

membrane perch against each other.

When

naming the five entities in Mirror and Cloak, the

artist aimed for a non-subjective presence that resists definition. To

objectively assign names befitting future beings that are not human, the artist

asked ChatGPT, then appended descriptive subtitles to complete five titles: the

futuristic Jin (“Quasar”), the numinous Beom (“Bolt”), Hui (“Sparky”),

efficient yet mutant, Yeon (“Odin”), more human, and Q (“Tinker”), flamboyant.

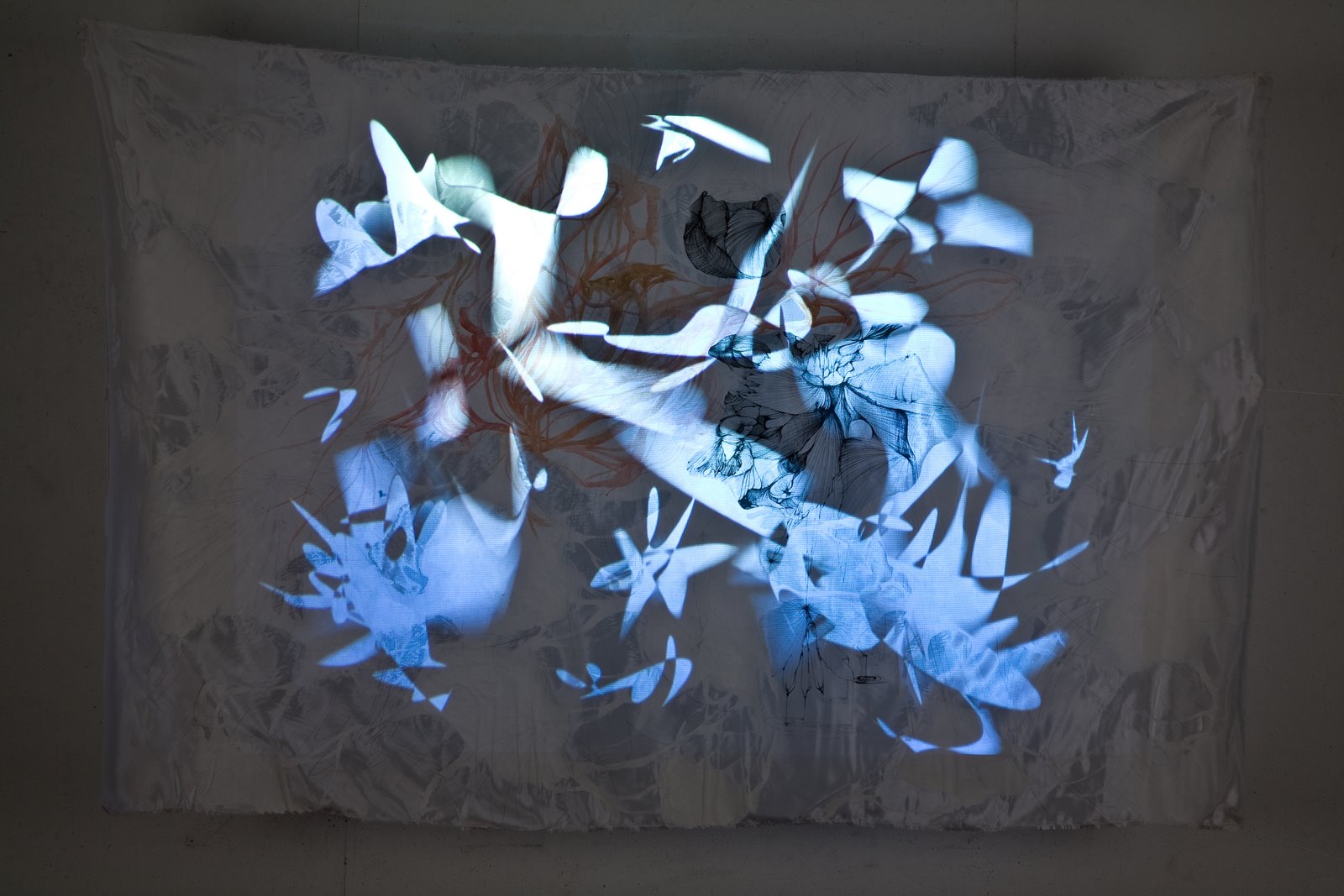

What

is striking is that once Hkason began to overlay light and shadow as a single

device onto installations in earnest, the work no longer regarded objects alone

as its subject; it expanded synesthetically into the domain of spacetime. This

expansion is immediately linked to the drawing series ‘Windscape’ (2011–), a

medium not readily associated with the artist and seemingly quite distant from

recent work.

Hkason’s approach to the body is distinct from Stelarc’s extended

body, Rebecca Horn’s anthropomorphized machines, or the many artists who have

used the body as a site for history, narrative, and speech. If we scan the

art-historical trajectories along which the body has occupied different

positions across eras, Hkason’s perspective on the body comes across as

markedly different.

A boundary draped across

Confronted with Platform-L’s Live Hall and its high ceiling, the artist

reportedly envisioned a fashion-show-type performance. Typically, a fashion

show places the runway at the center with viewers seated in the dark on either

side to gaze at the stage. In Hkason’s (so-called) fashion show, however, the

audience is placed in the opposite position. Within a single space that lacks a

clear division between model (object) and viewer, spectators naturally must

move to capture the performance’s varied angles and motions in detail. This

approach resonates with the Spanish choreographer María José Ribot (La Ribot),

who attempted a rearrangement of the audience–stage relationship in Panoramix(1993–2003).³

Hkason structures the performance in three chapters—Part A: movement; Part B:

fastening–unfastening emulation; Part C: mingling of body and space, dance. The

runway’s fixed routes and repertoire—walking, turning, posing—are mixed and

expanded by the roaming spectators, opening a new scene.

Projections of light and sound

In this performance, completed in collaboration with sound designer Bokyung

Kim, sound functions as a reflective element that traverses the whole work. The

place that light and sound occupy in Hkason’s work recalls the phrase cited at

the start: “the stage that steps back a bit into the invisible.” In the dark,

the elements most immediately grasped by viewers are likely the five entities

picked out by spotlights, yet only through the light and sound projecting

across the space, and through shadow, are the stage and the body completed. In

the 2023 solo exhibition 《Gametophyte》 as well, the long pool at the center—the wave of water and the

reflection of light—functioned like a mirror, enveloping the space. In most

cases, including From Loop to Tail(2022), the way

Hkason brings light into the work is indirect. Reflected at multiple angles,

the light continually diffuses through transparent materials, turns into

shadow, and circulates across the space as a secondary or tertiary passage.

Turn, pose, turn

In truth, my curiosity about Hkason’s work deepened upon encountering the early

drawings. Asked about the relationship between those drawings and current

media, the artist replied: “The plane felt too close to my body, so I wanted

some distance through other media. Immersion is good, but when the body gets

too close, the pain was greater.” Yet even a decade later, at the site of

performance, drawing was still present—now as a kind of spatial drawing that

continually crosses and accumulates (through the entire space) by means of

light, shadow, and sound. Drawing on references spanning fashion and

dance—Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet and

Alexander McQueen’s 2005 S/S collection show It’s Only a Game,

among others—Hkason sought to explore “spatial drawing” in greater

dimensionality and to test the mutability of space. Composed as a trilogy, the

performance Mirror and Cloak switches rapidly

between clearly differentiated parts; among them, Part C (where the artist’s

intention is particularly legible) unfolds as follows:

dance

– (on/off) in a new space

begin state changes (sensation: solid–liquid–gas, continuous motion,

transformation) – 2 minutes

(repeat fastening–disassembly–fastening) (stack, break, bind, unbind, wear,

remove, wrap the body, sweep down the body, strip, unfurl, fold, lengthen,

shorten, expand, contract, freeze, thaw, twist, disintegrate, join, conceal,

reveal)

(stopwatch) (the sound of dancing) (infinite space) (infinite body)

(transition) (derailment) (it changes and is renewed)⁴

A body that wears the stage, a stage that wears the body

Perhaps “mirror and cloak” extends beyond the title of a single performance and

suffices to condense Hkason’s oeuvre to date. The artist’s work expands along

two axes—transparency and opacity—where opposing attributes—cold/hard and

flexible/delicate—continually mingle and collide, each draping over the other.

In the artist’s comment on early drawings—“I felt suffocated by the sense of

confining a material to a form, so I expressed only with lines”—we can already

surmise a vector outward from the given plane: from plane to volume, from

volume to space. Thinking of an artist who now considers the scalability and

mutability toward space—beyond “the body’s variability, temporality, and

duality”⁵—I return to the line below:

“The

‘body,’ therefore, is already a stage.”⁶

¹

Philip Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy, The Stage,

trans. Man-soo Cho (Moonji Publishing, 2020), 32.

² Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans.

So-sung Jung (Doseo Munhwasa, 1994), 472.

³ André Lepecki, What Is Choreography?, trans. Ji-yoon

Moon (Hyunsil Munhwa, 2014), 174–177.

⁴ Interview with Hkason by Bo Bae Lee, Oct. 2024.

⁵

Interview with Hkason by Bo Bae Lee, Oct. 2024.

⁶

Philip Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy, The

Stage, trans. Man-soo Cho (Moonji Publishing, 2020), 43.