Imagine, make things up, generate the moment!

Suppose that all of us—consciously or unconsciously—perform different roles on

the stage of varying relations, situations, environments. Here and now, you in

the gallery appear as if you are someone else. This isn’t my idea but that of

social psychologist Erving Goffman. Humans, intentionally or not, change

settings, appearances, and attitudes to form appropriate impressions for each

relation—a tendency he calls the “definition of the situation.” I invoke this century-old

theory because it gives the insight that even if a “true” self is an illusion,

“situational” selves exist according to circumstance. From social roles at

work, school, and home to intimate spheres—lover, family, friend, colleague,

acquaintance—our appearance shifts, knowingly or not, depending on situation

and relation.

From this perspective, I wonder if the artist is strategically

presenting through Club Reality how we “perform in

everyday life” (to borrow Goffman’s subtitle). Here, one self-assigns fictional

identities—freelance commercial writer, nude model, fifth-year college student,

izakaya part-timer, high schooler—and faces unfamiliar situations weekly with a

new identity. The self-presentation that would ordinarily operate by instinct

collapses at each moment here, heightening our awareness. The emergence of

selves that slip and stutter—responding within relations or situations,

patching gaps—paradoxically confirms that we perform and react at every moment

in society. One participant wrote with self-deprecation in their diary, “Maybe

my whole life is fake; I could just express myself as I am—why is that so

hard?”

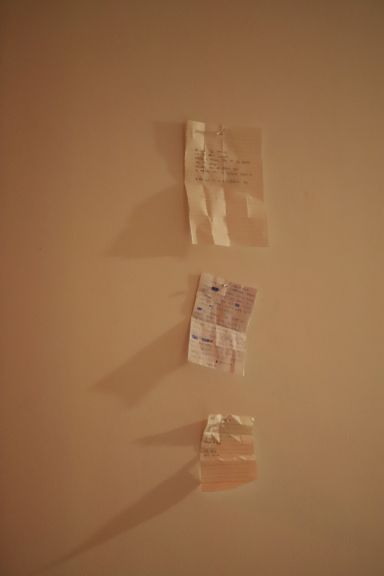

But

the artist doesn’t stop there—he goes a step further. Each of the ten weekly

episodes proposes a special situation. Take “Half-Drunk Bottles” as an example:

you write down a memory you want to hide, draw lots, then recount someone

else’s memory as if it were your own. With only a few clues on the paper, you

must improvise—imagine and make things up. As with Tolentino’s reality-show

episode, memory is prone to distortion. Here, the premise is that the memory

was created by a fictional “me.” Then it is reconstructed yet again through

another’s imagination.

Passing through the steps “past experience (fact) →

distorted memory → variation by a fictional identity → reconstruction by

another’s imagination,” essence vanishes and only the plausible cover story remains.

To borrow the artist’s words, “all data is lost and volatilized.” Isn’t that

interesting? In the end, the original fact doesn’t matter. What matters are the

flashes of moments that are generated and emerge as we flounder through clues,

reorganize, and perform.

I think the artist’s intent does not lie in identity

or memory as essence, but in mapping the topography of relations that make them

emerge differently in each moment. In Rabbit Hole 2052 (2022),

a cross-referential work to Club Reality, the setting

is a “prequel”—in other words, the main story exists only in imagination. Club

Reality likewise exists only as innumerable records: five codes;

some 600 documentary photographs from the site; around 400 pages of testimony;

over 200 drawings; interviews. In the exhibition assembled from such fragments,

we strain to find Club Reality’s essence, only to fail;

at best, we faintly infer it by following “moments.”