Even though sculpture is one of the

traditional forms of art along with painting, the possibility that sculpture

could exist as a distinct category, not as a part of installation art,

architecture, or landscape architecture is quite rare. While painting was

recognized for its autonomy as the artist’s spiritual creation throughout the

West and the East for a long time, sculpture was still mostly subordinated to

the object that it represented ― as a monument for

something or used as a landmark. Also, it is impossible to enter into the

profession unless you are trained with enough skills, because sculpture is

strongly bounded by physical and material conditions. However, since sculpture

is an artistic discipline that requires such high technical training, it is

difficult to prevent it from being penetrated by industrial technology that is

related to the material’s production and processing.

Therefore, the predicament of sculpture is similar to that of photography

rather than painting. In both fields, there are conventional distinctions

between the fine arts and the commercial arts but the basis is unclear.

Sculpture and photography can hardly be considered as autonomous art forms

because their social utility have not been entirely exhausted. The uneasiness

of using machines in art-making is displayed in their spiritual value, the

unskilled expression of forms, and the pursuit of accidental effects. Like that

of a photographer who should not be a photo machine, the sculptor tries not to

be a sculpting machine. But how? How could the body of a sculptor avoid from

being a sculpting machine? How can the object made by a sculptor distinguish

itself from any other machine-made objects?

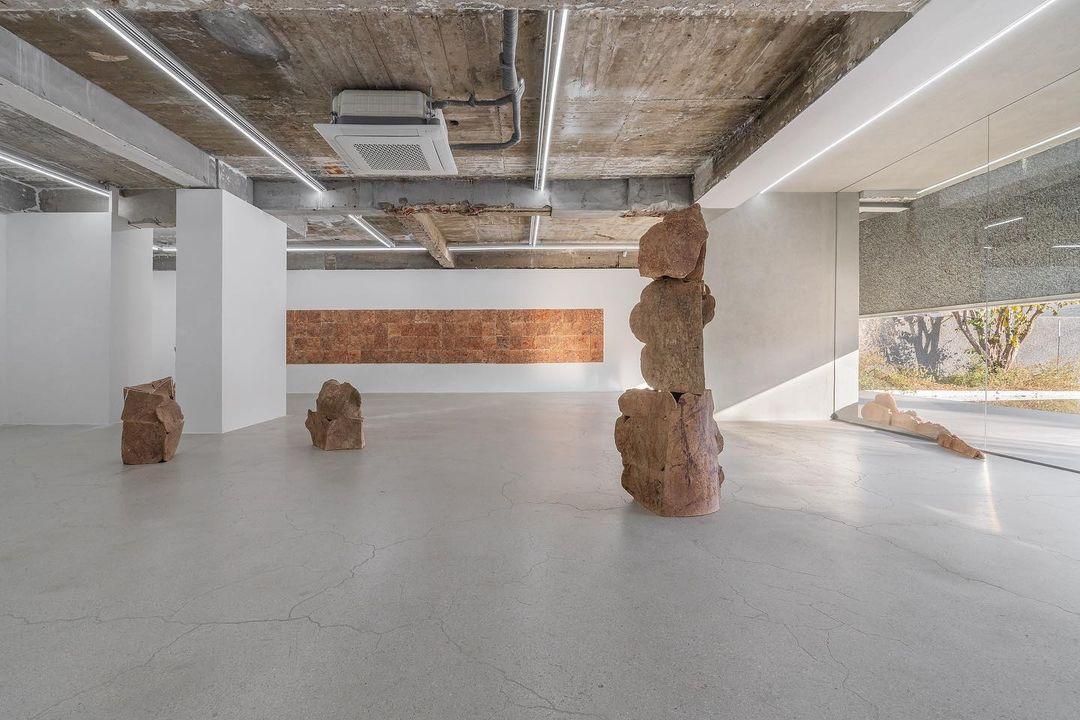

Isaac Moon responds to the difficulty with a

paradoxical approach of being a machine himself or learning from a machine. But

he takes the attitude of a wizard’s disciple who clumsily imitates his

teacher and causes unpredictable accidents, instead of a disciple who

mechanically follows the teacher. Generating different outcomes, Moon’s

synthetic resin sculpture is made by trial and error during the process of

imitating the working method of a CNC cutting machine that is controlled by a

3D modeling software and computer.

Assuming the position of the non-expert who

cannot skillfully handle the computer programs, related devices, and various

plastic materials, the artist reproduces the method of industrial sculpture

with his hands and finds something useful, or even beautiful, in the accidents

that happen through the process, which he applied in the subsequent works. Moon

is not trying to simply appropriate the industrial method and style like a

robot, but he is also not unilaterally converting the graphic tools and industrial

devices into artistic means. The artist is looking for something else. While

deviating from the conventional methods of dealing with materials and tools,

and creating forms, Moon seeks to produce a certain arrangement that satisfies

his eyes and hands, and finds a suitable connection between himself and the

machine.

Participating in 《Asia Kula Kula-ring》, the Asia creative space network exhibition at the Asia Culture

Center, Isaac Moon presented the working method in the fall of 2016 with Low-Storage

at Space 413. For the piece Standard Prototype, Moon

randomly projected images of multiple viewpoints of basic forms (cylinder,

torus, kettle, etc.) provided by a 3D modeling software onto hexahedral

styrofoam material (Isopink or Neopor) by shaving it with a hot wire, coloring

it , and applying an epoxy coating.

The method developed into a series of works

including Expanded Prototype, Arms and Hands, and

Head of ST John, that were presented in the group exhibition 《Things: Sculptural Practice》 held at Doosan

Gallery in early 2017. These artworks were produced like a kind of tutorial

that demonstrated how to create sculptures with the method that was used in

making Standard Prototype.

In Expanded Prototype, by

applying the basic 3D forms on screen to the styrofoam mass outside of the

screen, Moon experimented with the cutting method that resulted in a third

form. Based on the work, Moon challenged himself by using more complicated

forms, like the hands and arms of the human body in Arms and Hands. He

collected various forms of hands and arms from free 3D modeling sources found

on the Internet and applied the same cutting method to them. Lastly, in the Head

of ST John, Moon applied all of the methods he had been experimenting

with, and created a 3D image of the head of St. John as depicted in classical

paintings.