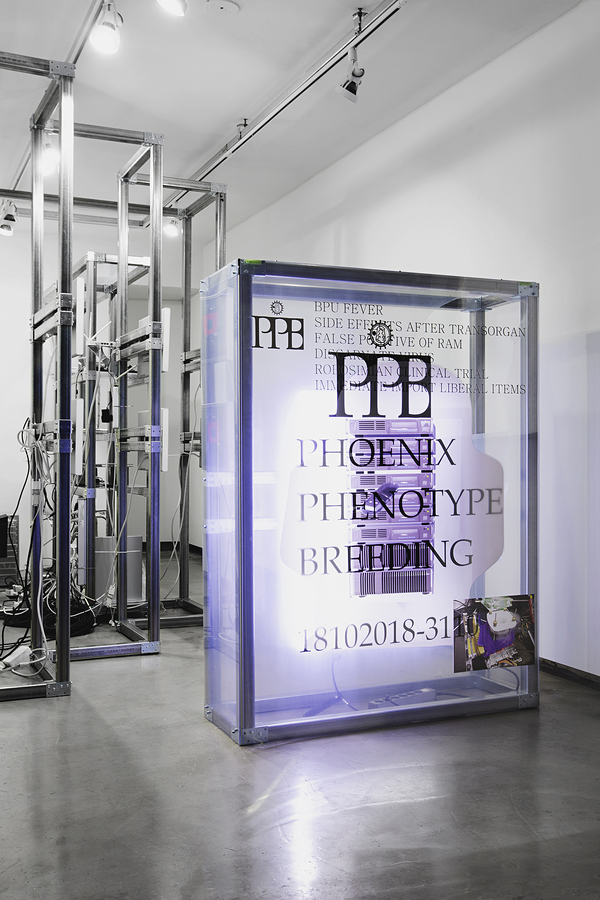

After PPB,

Koo’s trajectory increasingly widened the gap between software and the body,

intensifying the heterogeneity of their connections. While PPB visualized

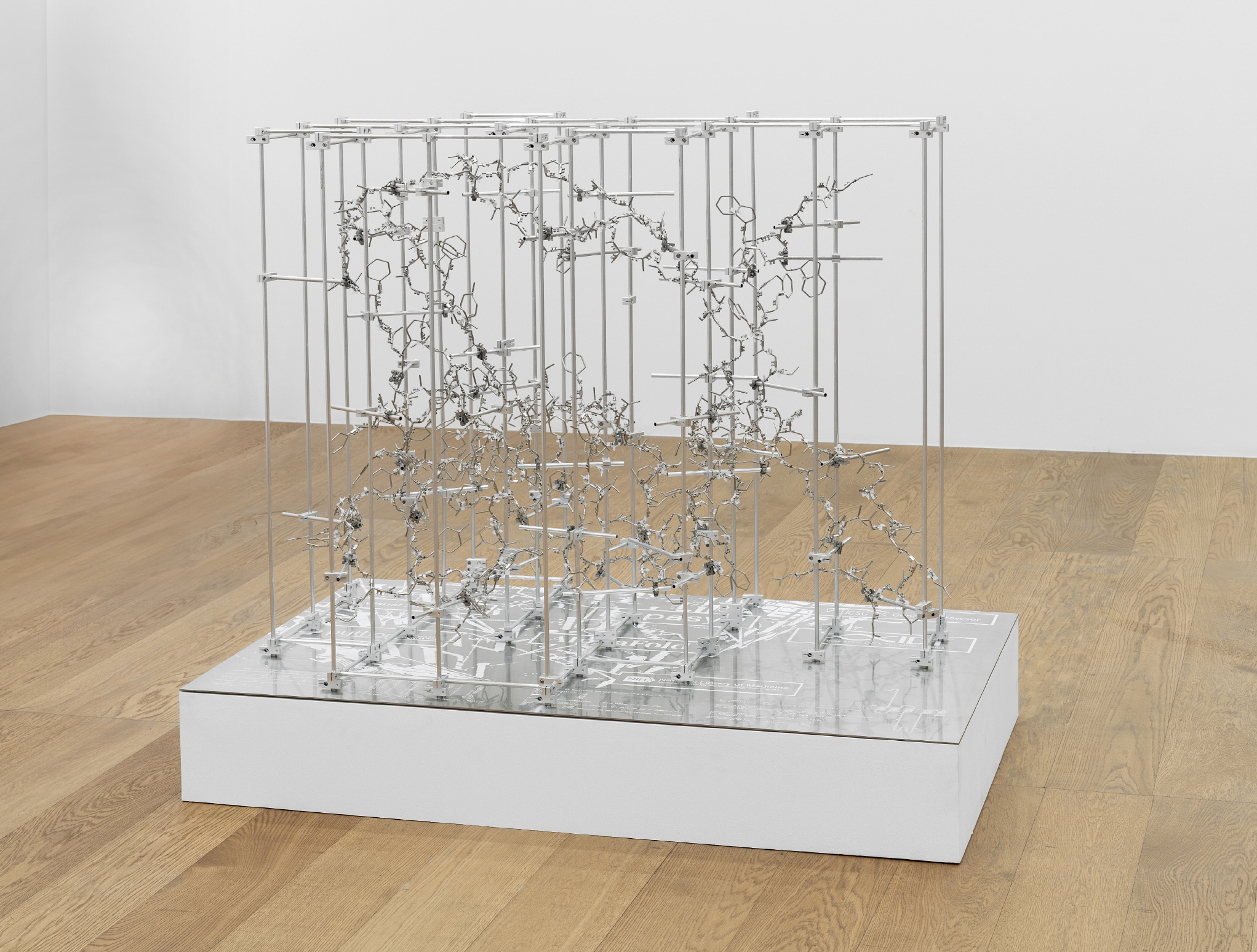

the workings of 3D computer graphic programs such as Rhino or 3Ds Max, Development

of editing methods for website structure (2020) analyzed the

composition of codes that determine website properties, rendering them into

perceptible structures.

The

residency project 《On the Growth

and Form of Software》(Incheon Art Platform G3, Incheon,

2021) delved into an even smaller unit: the process of specific source codes

being revised. The direction of his work thus evolved — from the operational

logic of graphic tools, to the design blueprints of virtual spaces, to the

formative processes of unit elements themselves. Like progressing from

compounds to molecules, from molecules to atoms, his explorations of software

have increasingly turned toward fundamental structures of media.

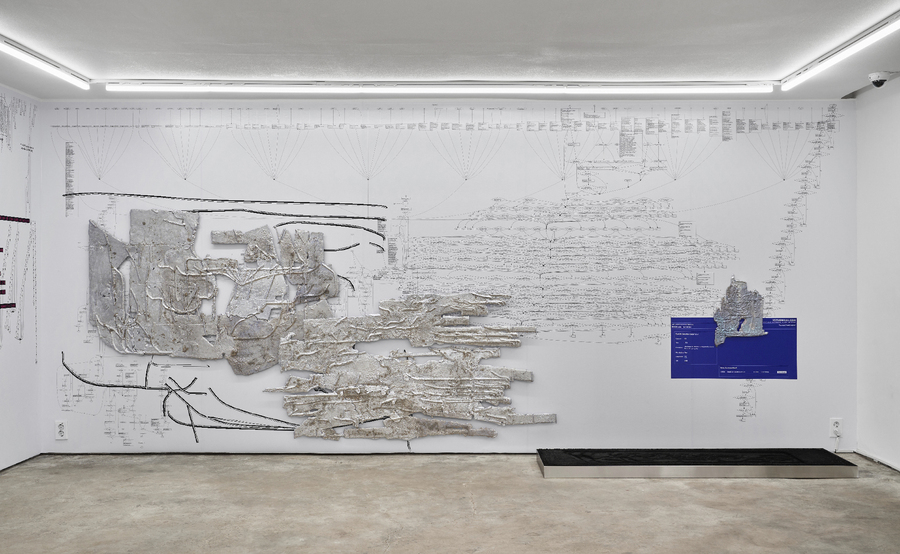

Interestingly,

even as the abstraction of his subjects intensifies, the materiality of his

works grows heavier. Development of editing methods for website

structure, which visualized the structures of six major art-world

websites, functioned like an experiment in sculptural evolution, from line to

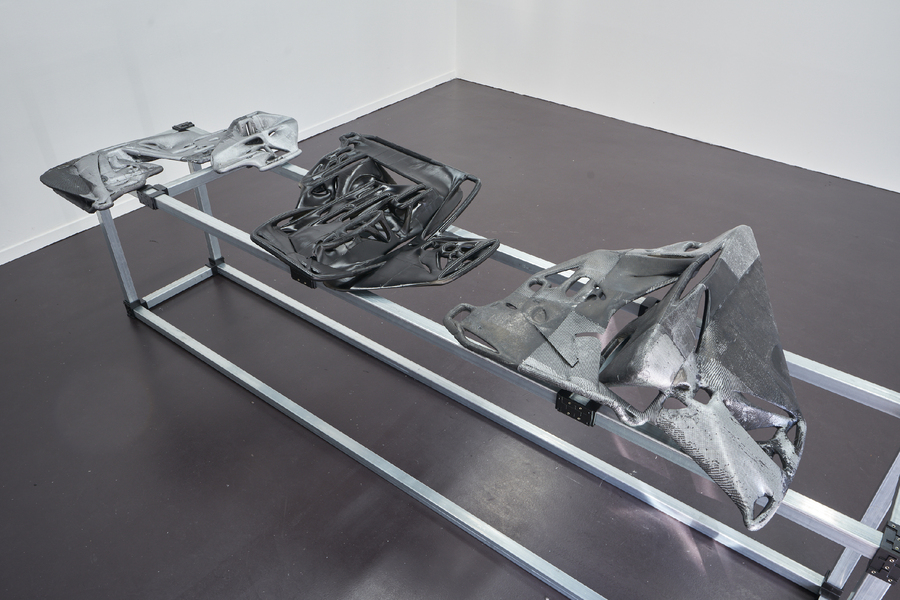

mass, showcasing multiple stages of 3D-printed outputs. More strikingly, 《On the Growth and Form of Software》

presented the new work Soft Muscle (2021), which

displays overwhelming scale and material force. By likening the process of

developers debugging and completing code in open-source communities to the

growth of muscles, and by visualizing code’s growth through 3D printing with

carbon fiber (CFRP) molding and water-transfer films, Soft Muscle materializes

the toughness and density of muscle fibers.

Carbon

fiber is a material often used in high-powered muscle cars, its woven patterns

and textures evoking muscular men or powerful machines. These grotesque black

masses, immense in scale and with artificial textures, radiate an uncanny

grotesque sensibility. That they visualize the formation of immaterial,

abstract code only heightens the dissonance between the palpable intensity of

materiality and the abstraction of code.

To

give bodies to code — symbols complete in themselves — arises from our human

cognition, which cannot perceive abstractions without concrete forms.

Translating abstraction into form recalls inorganic matter becoming organic,

evoking biological analogies. Koo has indeed drawn on concepts from organic

chemistry and biology: likening the selection of base tags in website source

code to genetic scissors, adopting molecular visualization methods to shape

website codes, borrowing exhibition titles from classics in biology.⁴ Among

such organic analogies, the most crucial is reverse transcription.

Viruses,

unable to metabolize on their own, parasitize host cells. Some viruses, unlike

normal transcription, reverse-transcribe RNA into DNA and insert it into host

genomes. Viral DNA embedded in host DNA then triggers different mutations. Koo

interprets such reverse transcription — which generates difference — as a

search for alternative possibilities.

Since

Plato, images have been regarded as secondary to reality. Yet in today’s world

of Photoshop, Illustrator, and Rhino, where objects can be extracted from

images, the real has become something that arrives after images. In this

reversal of value systems, Koo’s act of giving bodies to code reflects the

epochal shift of contemporary media paradigms, wherein software transforms the

very essence of culture.

Visualizing

software recalls the dominance of media in our age, the hybrid senses of

contemporary humans inseparably synchronized with programs and devices. But

above all, what Koo envisions is the potential to reverse-transcribe

human-centered sculptural language and object-centered exhibition spaces into

the immaterial language of programs, thereby generating new, unimagined

mutations. We can only anticipate the healthy emergence of such mutants.

1.

Jamyoung Koo, “Artist Talk with Critic Jihong Baek,” 《Development of editing methods for website structure》 Exhibition Catalogue (Willing N Dealing, Seoul, 2020), p. 43.

2.

Ibid., p. 44.

3.

This line of thought recalls Marshall McLuhan’s conception of media, but Koo’s

perspective is relatively more object-oriented, compared to McLuhan’s

human-centered view of media as extensions of human senses.

4.

The exhibition title 《On the Growth

and Form of Software》 borrows from D’Arcy Wentworth

Thompson’s On Growth and Form (1917), which systematized the

morphological development of organisms.