In

1968, Jack Burnham, in his essay “System Esthetics” published in Artforum,

argued that art was moving from an object-oriented to a system-oriented

culture, and that this shift would emerge not from objects themselves but from

the processes of becoming objects. He also claimed that the distinctive

function of contemporary art no longer lies in its material persistence, but

rather in the relations between people, and between people and their

environments — that decisions regarding the use of technology and scientific

information would, literally, become art.¹

More

than fifty years later, many of Burnham’s predictions have become everyday

reality. The shift from a world structured by objects to one structured by the

invisible flows of information and technological sophistication is precisely

the world we inhabit today.

Koo’s

practice is not about the contents delivered by media but about deploying the

problematics of media itself as sculptural vocabulary within today’s media

environment. Grounded on the infrastructure of information technologies

operated by software and hardware, he constructs new hardware to make visible

the ways in which software functions.

In

his work, hardware is not simply the machinery that enables programs and

information to run. Rather, hardware becomes a frame to demonstrate how

programs and information themselves “exist.” He envisions this system as a kind

of “body,” one whose forms emerge from reading the flows of code that make

software usable. The works we encounter are thus “bodies” — but bodies composed

of software, that is, the materialized surfaces of code flows.

This

constitutes a kind of aesthetic decryption of the media environment — so much

of which is symbolized and coded — that dominates our world today. Underlying

this approach is an attitude of reflection: what forms does a world ruled by

software take, and, through it, what forms does our own way of life assume?

Lev

Manovich, in Software Takes Command, calls software

“something else,” pointing out that all the “cultural software” used by

millions is merely the visible portion of a much larger software universe.² He

also argues that the material elements constituting “culture” today, as well as

the systems and processes that operate it, must take into account not only the

“visible software” that consumers use, but also “grey software.” He concludes

that our society is a “software society” and our culture a “software culture,”

because software plays a central role in both the material and immaterial

structures of our world.³

If

we accept that Baudelaire’s notion of modernity still holds relevance, then the

economic, political, and cultural conditions that shape the “software society”

inevitably become matters of artistic concern. Yet these references still

appear largely object-oriented. In contrast, what Koo pursues is a

system-oriented approach — plunging into the state of code itself to embody it

as art.

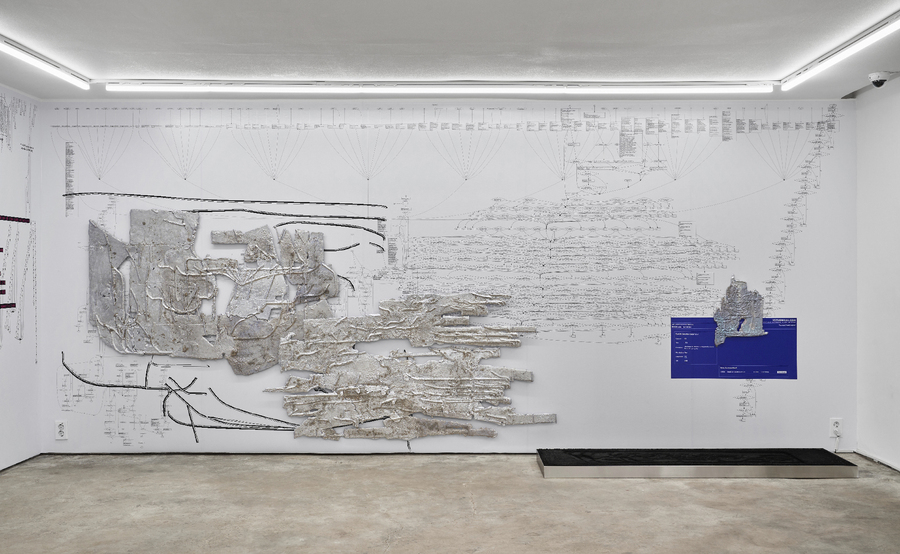

To

materialize the coding of information, Koo borrows engineering and biological

models for his hardware frameworks. In PBB (Phoenix

Phenotype Breeding, 2018), he appropriated the hardware display systems of

digital billboards, translating the latent temporal suspension of viruses

dormant within computers — not yet manifested but present — into architectural

lightweight steel frames. This revealed his particular interest in the

“internal.” From this point onward, his method has been to externalize those

systems originally hidden inside technologies, surfacing the structures that

govern the storage and circulation of information.

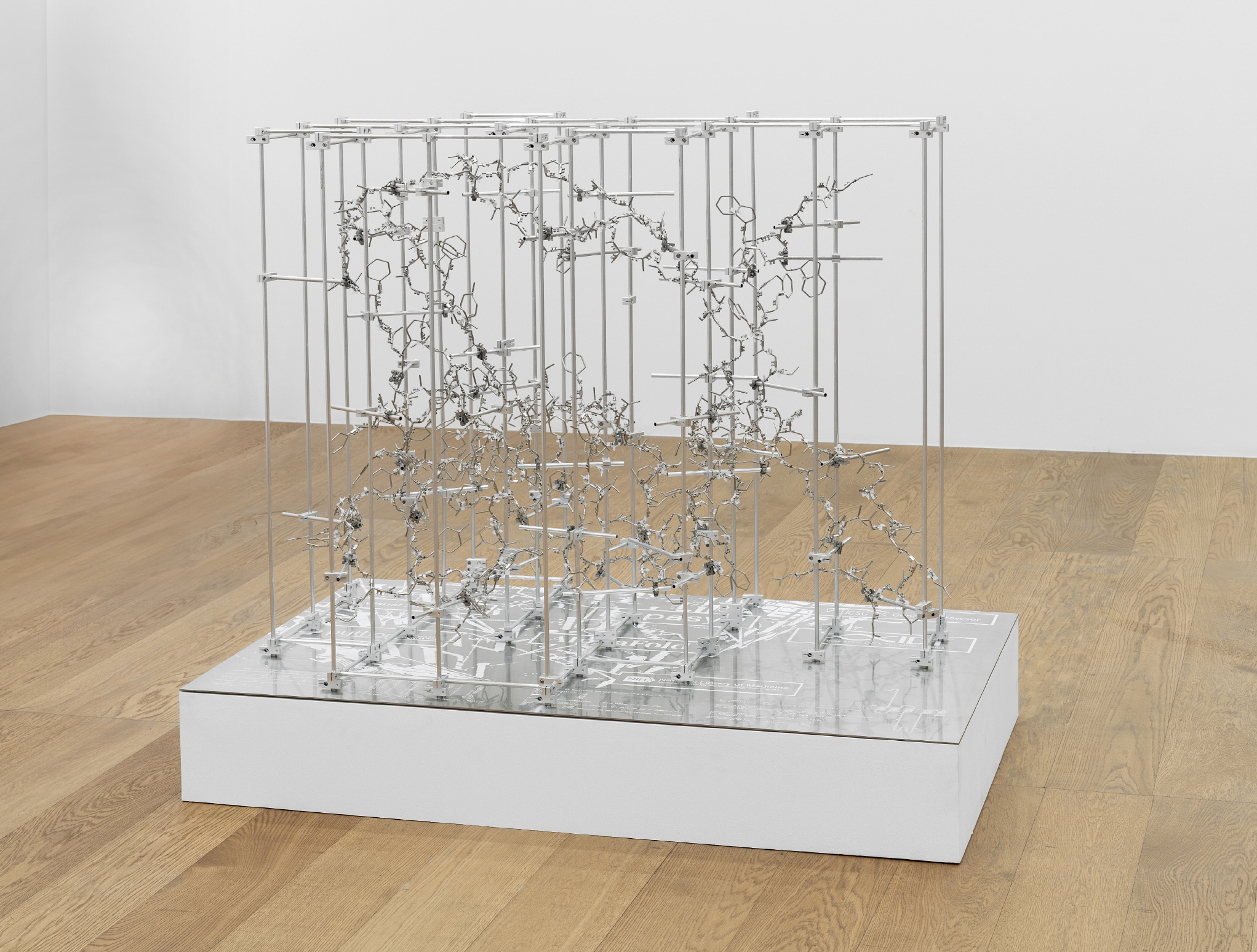

In

his solo exhibition 《Development of

editing methods for website structure》(2020), he

analyzed the code and HTML that underpin museum websites, hybridizing them with

systems from biotechnology, molecular biology, and computer software. This

project began with questions arising from the pandemic period, when viewing

exhibitions online — experiencing art in mediated spaces — became commonplace.

By transposing HTML from a museum website into molecular structures, he

produced forms that were 3D printed and arranged similarly to the layout of

large servers. The suggestion here is that the coded spatial structures of

websites constitute a new “real” in which we experience art. Yet this real is

not offered as representational message, but as manifestation through the forms

and structures of technological language.

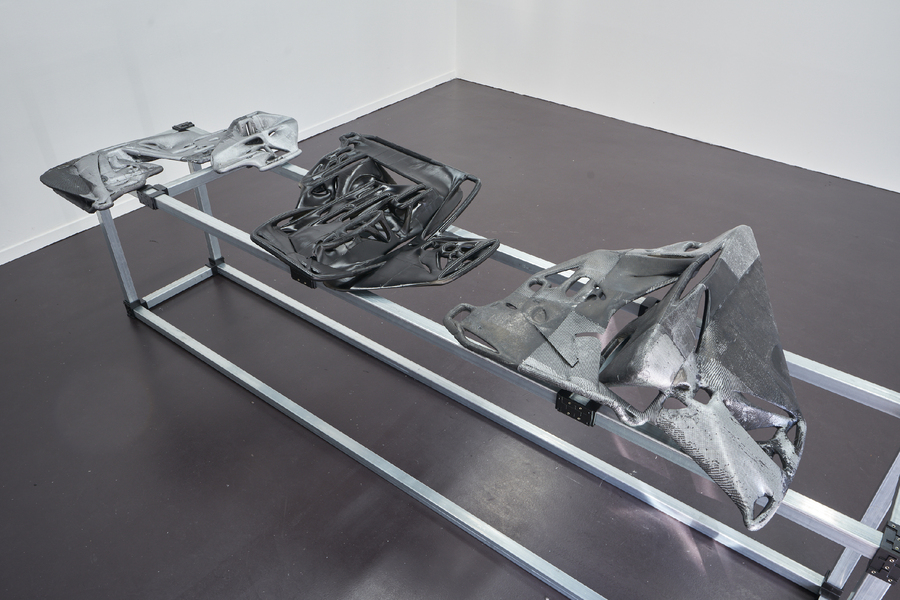

In

his solo exhibition 《On the Growth

and Form of Software》(Incheon Art Platform G3, Incheon,

2021), he took yet smaller units: the processes of specific source codes being

revised through developer-community discussions. He generated sculptural forms

resembling muscle bundles to represent the growth of code, using carbon fiber —

the industrial material most analogous to muscles — to visualize them. The new

work Soft Muscle(2021) materializes code’s growth as

the generation of muscles, overlaying 3D printing with CFRP molding or

water-transfer films to effectively embody the toughness and density of

muscular fibers.

Carbon

fiber is often used in the interiors of muscle cars, with woven textures and

surfaces that evoke muscular bodies or powerful machines. These large, black,

grotesque masses with artificial textures evoke a bizarre grotesque quality.

Realizing that these forms visualize immaterial, abstract code only amplifies

the gulf between the tangible intensity of their materiality and the intangible

abstraction of code.

To

give form to code — already complete as symbols — is to appeal to our human

cognition, which cannot perceive abstraction without concrete forms. To

visualize abstraction recalls the transformation of inorganic into organic,

evoking biological analogies. Koo frequently draws upon concepts from organic

chemistry and biology: comparing the selection of key tags from website sources

to genetic scissors, adopting molecular visualization methods to give form to

website codes, borrowing exhibition titles from classics in biology.⁴ The most

significant analogy, however, is that of reverse transcription.

Some

viruses, unable to metabolize independently, parasitize host cells. Certain

viruses produce DNA from RNA in reverse — a deviation from the normal process —

and insert it into host genes. The DNA altered by viral RNA produces different

mutations. Koo regards such reverse transcription, which generates difference,

as a search for alternative possibilities.

Since

Plato, images have been regarded as secondary to the real. But today, in the

age of Photoshop, Illustrator, and Rhino, where objects can be extracted from

images, reality itself has become something that arrives after images. In this

reversal of value systems, Koo’s act of giving bodies to code reflects a

paradigm shift in which software transforms the essence of all things that

constitute culture.

Visualizing software recalls the dominance of media over

our present age, the hybrid sensations of contemporary humans who cannot help

but synchronize with programs and devices.

But

above all, what Koo dreams of is the possibility of reversing physical,

human-centered sculptural language and exhibition spaces into the immaterial

language of programs, generating unimagined new mutations. We can only await

the healthy emergence of those mutants.

1.

Jack Burnham, “System Esthetics,” Artforum, September 1968, p. 31.

2.

Lev Manovich, Software Takes Command (New York, London: Bloomsbury

Academic, 2013), p. 7.

3.

Ibid., pp. 21, 33.

4.

The exhibition title 《On the Growth

and Form of Software》 borrows from D’Arcy Wentworth

Thompson’s classic On Growth and Form (1917), which systematized

morphological development in biology.