Gooroom,

Sun, Red Star, Creeper, Stone, Hare, and Cascade — they share a common ground:

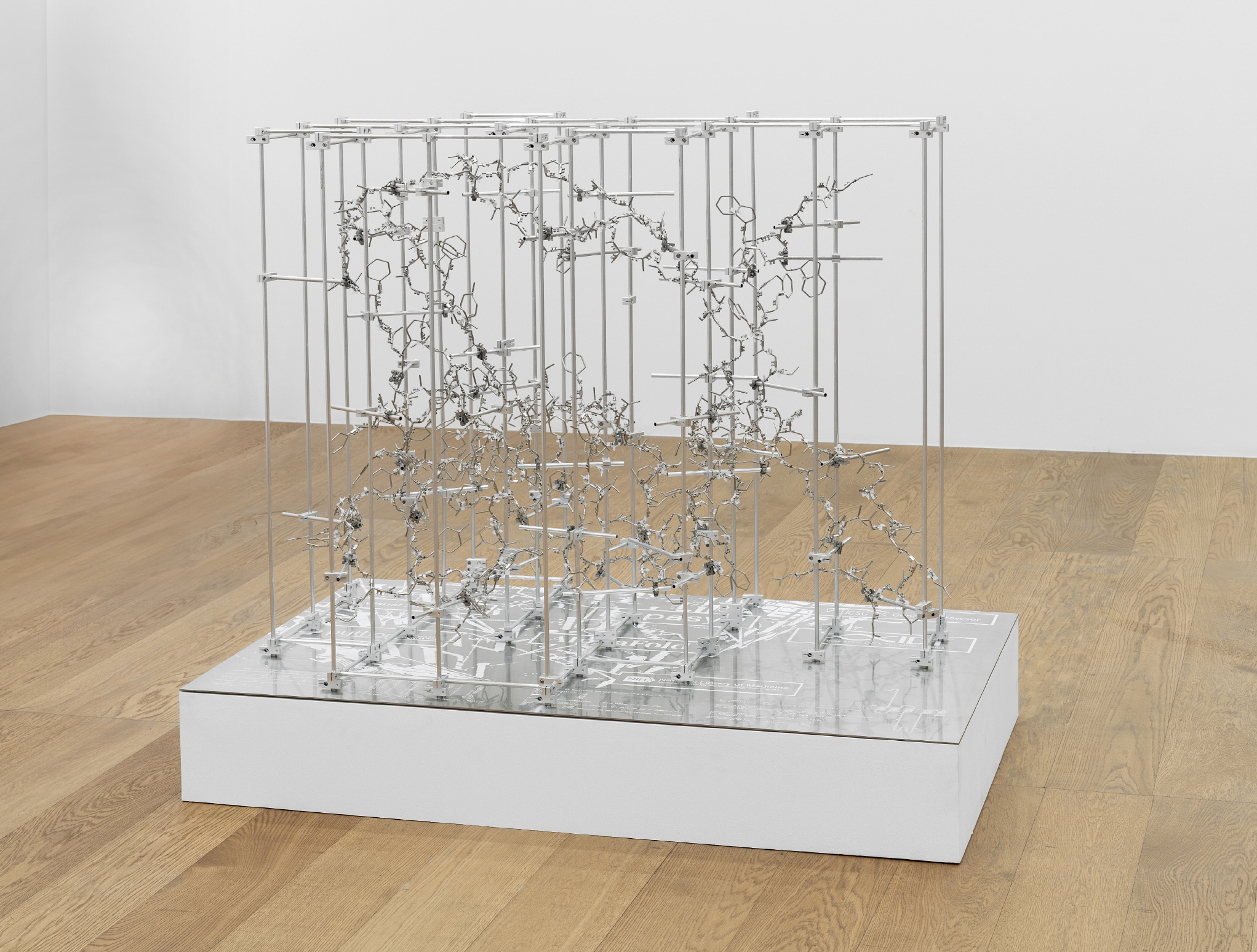

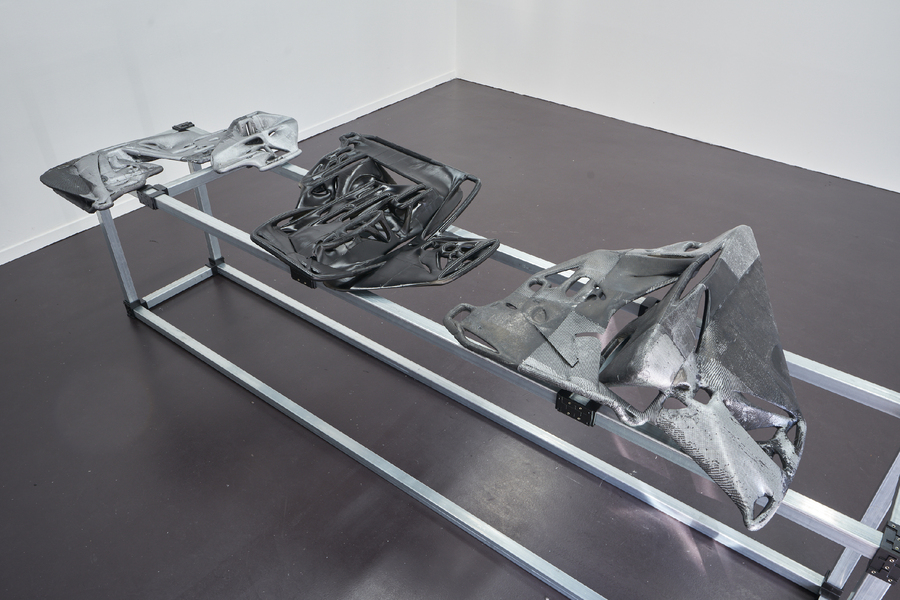

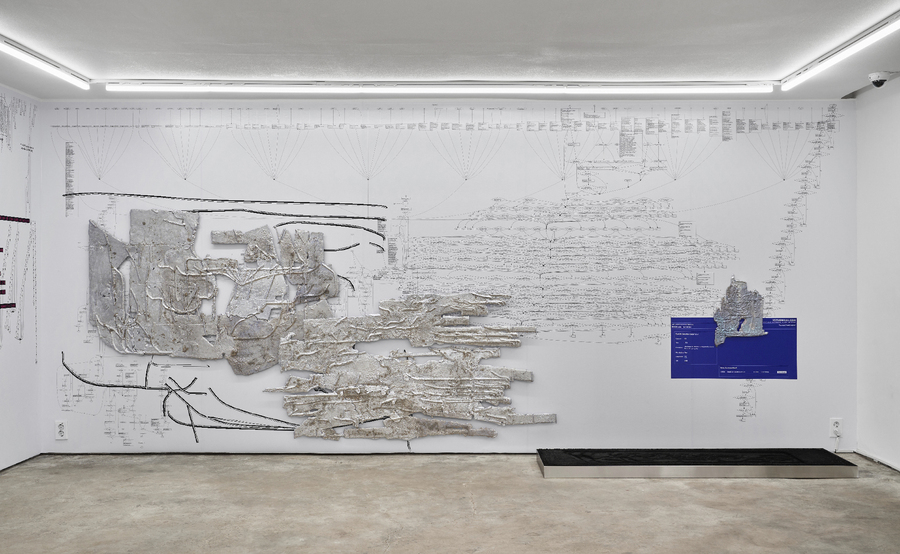

nature. While planning 《Monocoque:

Principles of the Garden》, Koo selected computer

programs named after natural entities. He had already given biological

principles to his forms in past works, since he regarded the operation of

software as not so different from that of living organisms.

Software

named after nature, or nature renamed through software, crosses the binary

structure of the natural and the technological. This act of crossing is as

difficult and risky as reconstructing the irreproducible. Yet if one accepts

the assertion that “nature is no longer the pure and simple first nature but a

cybernetic nature,”⁷ —

if one accepts that the gradual machinization of the “artificial earth” is irreversible,⁸ then one may also nod to the

idea that art will become a speculative circuit that appropriates cybernetics,

raising new questions about technological diversity.⁹ Seen this way, opening a hole

into software’s

concealed underside to lead the deconstruction of nature and technology through

the “principles

of a garden”

is not at all strange.

Gardening

is perhaps one of the oldest technologies for relating to nature. A garden

evokes images of ornate landscaping or a calm space for midday rest. Yet

beneath its soil, weeds, insects, and moles gnawing tree roots coexist. To

understand the technology of the garden is to understand this riot of life. Koo

digs beneath the software’s surface, uncovering the tumult of source code

hidden beneath logical language, and individuates it. Not trees, but beneath

the trees. Not roots, but beneath the roots. Only by getting one’s hands dirty

with soil and dust, by digging down, can one know what lies there.

Footnotes

1.

Jamyoung Koo, “Only Frames Left, From a Worthless Beginning,” Artist Note,

n.p.

2.

Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI, trans. Roh Seung-young, Soso Books, 2022, p.

43.

3.

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “On Software, or the Persistence of Visual

Knowledge,” Grey Room 18, 2005, pp. 43–44.

4.

Alexander R. Galloway, The Interface Effect, Polity, 2012, p. 58.

5.

N. Katherine Hayles, My Mother Was a Computer, trans. Eunju Song and

Kyunglan Lee, Acanet, 2016, p. 70.

6.

Alexander R. Galloway, ibid., pp. 99–100.

7.

Yuk Hui, Recursivity and Contingency, trans. Hyuk Cho, Saemulgyeol, 2023,

pp. 255–256.

8.

Yuk Hui, ibid., pp. 75–79.

9.

Ibid.