A

monument is a public structure erected to commemorate a person or an event. It

is often a marker to celebrate a nation’s historical achievements, but

conversely, it also serves as an important symbol in rituals of remembrance

following great sacrifice, or as a pledge not to repeat past wrongs. The lesson

of a monument lies not in the success or failure of the past it stands upon,

but in its ability to rescue the present from failure—or at least to defer such

failure. In other words, a monument presupposes failure. Then, upon what kind

of present does Sunghyeop Seo’s Monument stand?

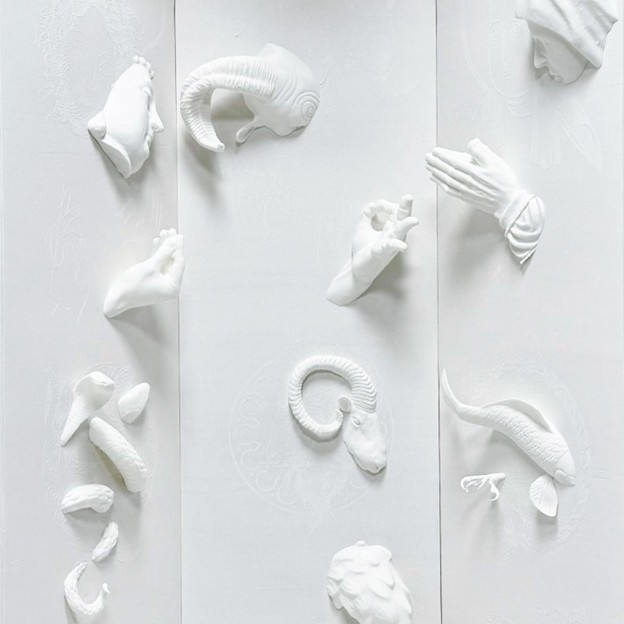

The

sculptural work, measuring 250 cm in height, is primarily composed of plywood

painted in ink. It combines a Doric column—one of the architectural orders of

Greco-Roman antiquity—with a tetrapod, a concrete structure commonly found

around breakwaters. While overall taking the shape of a tetrapod, the tips of

its four limbs are transformed into the tops of Doric columns, becoming

passageways through which sound passes. The two elements that compose this

monument are chosen types: representatives of vastly different worlds with no

shared origin, traits, or use.

Their encounter produces misunderstanding,

alienation, and disconnection—realities that lie beneath Seo’s Monument.

Likewise, the low narration that flows around the work and the unfamiliar

language inscribed on its column-topped forms underscore this. Written in

Polish, the text recounts anecdotes of mistranslation that arise when different

cultural spheres collide, and reveals the shortcomings of stereotypes. These

are the kinds of small, awkward missteps—conversations that slip between close

companions—that bring forth a wry, involuntary chuckle. Yet when these

seemingly trivial events are articulated as spoken narration and inscribed text

within Monument, they begin to raise questions about

individual positions within social categories.

Monument drifts

outside the functions of its two parent forms, orbiting without anchorage. It

is neither temple nor sea, unable to support or block anything. This

“placelessness” makes Monument easily

marginalized, hard to acknowledge. While we profess to embrace and welcome new

human and non-human members alike, we are often stingy when it comes to

granting them a proper place. (Think of the difference in reception between

refugees and tourists; the unease evoked by radical figures or hybrid objects

falls into the same category.) In reality, acceptance still matters:

recognition by others becomes the cornerstone of one’s place. In this sense,

the unfamiliar appearance and oblique speech of Monument are

disquieting, even threatening.

That which fractures familiar landscapes rarely

receives welcome. The courage to claim the right to be here, to carve out a

place where none exists, and to unsettle others—these are the gestures of Monument.

It is an anchor preventing concepts like freedom, equality, and inclusivity

from dissipating into empty abstractions or evaporating as hollow declarations.

If the present is not to fail, more objects like Monument must

exist. By its very being, Monument testifies that

we must not grow accustomed to the languages, powers, relations, and structures

that hold up reality. What it asserts is a reminder: if we fail to listen when

it declares its role in safeguarding rights, we may overlook the fact that

someone’s very existence can be denied.

Monument states

firmly yet gently, “My place is here.” Without shouting or rage, it asserts its

presence. To grasp its rhetoric, we must reconsider its two parent forms. Both

column and tetrapod are proportionally stable, yet rarely stand alone. They are

parts of a whole, requiring the presence of others. To perform their function,

they must stand shoulder to shoulder with their likenesses. This reveals the

interdependence of objects, that no being can exist in isolation.

It is

precisely this interdependence that distinguishes Seo’s Monument from

other monuments and equips it with a strategy to redeem today. It insists that

the subject who creates a place must be oneself, not dependent on another’s

approval, while simultaneously turning outward. At times, it exposes its own

insufficiency, extending a hand to others. The union of Doric column and

tetrapod is solidarity among those left alone—a greeting of welcome to new

beings.

Bibliography

Kim,

Hyun-Kyung. Person, Place, Hospitality. Moonji Publishing, 2015.

Azuma, Hiroki. Philosophy of the Tourist. Translated by An Cheon, Rishiol,

2020.