A

relatively large volume of texts has been produced in a short period of time on

the work of Sunghyeop Seo. This seems to be because the formal qualities of his

practice and the conceptual nodes underpinning them interlock rather tightly,

persuasively presented as a distinctive visual language. Indeed, the format and

degree of completion of his work, bound to its scale, have acquired a

compelling visuality. His sculptural forms at times extend into intersections

with performance, expanding into auditory impressions or experiences, and

thereby advancing beyond fixed forms into independent image-based

possibilities. In broad terms, this is the usual summary of his work:

monumental, vertical forms reminiscent of memorials; formal qualities linked

with sound; sound physically generated through activating the work itself; and

all of this tied back to what he names “topology” and “hybridity.”

First

and foremost, this “topology” can be regarded as the core of his practice. Seo

has consistently contemplated the points at which heterogeneous media

intertwine, naming the methodology of their entanglement as “topological” and

defining the sensations derived from it as “topological sense.” As is well

known, the concept of topology is used to indicate structural or symbolic

position. In other words, it is useful for discussing relationships among

individuals and groups within cultural or social contexts, or for examining the

perception and positioning of concepts and ideas. Topology presupposes

“relation,” and relation entails “state.” By scrutinizing the criteria

sustaining this state, topology provokes thought about socio-cultural

relationships and dynamics beyond mere physical positioning.

The

artist seeks subversion and transformation of topology by intermixing and

intersecting multiple elements within his work. For example, he collapses the

distinctions between East and West, tradition and contemporaneity, sight and

sound, and even between performer and audience within the structure of

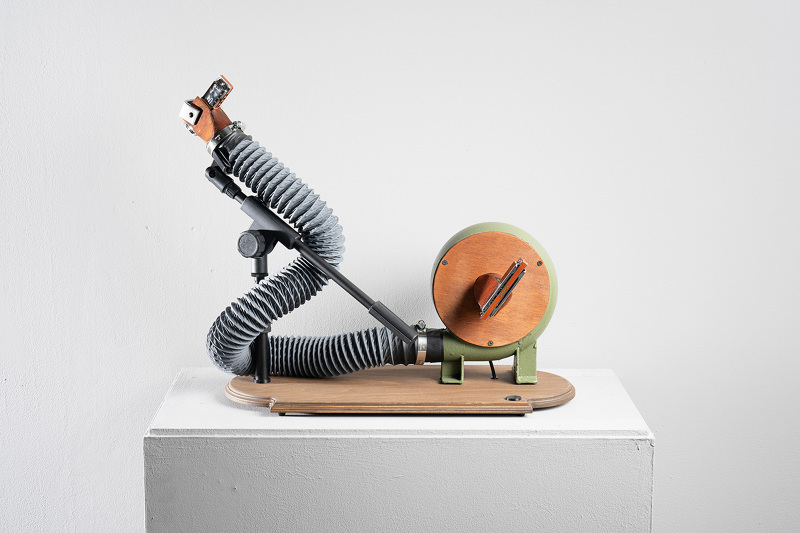

exhibition. In his solo exhibition 《Performance for Topological Sense》 (2021,

This is not a church, Seoul), he built instruments—more precisely, he attached

Western decorative elements to instruments designed to produce Eastern sounds.

An instrument’s form and structure are bound to its intended sound. From this

perspective, decoration is inevitably secondary. Yet these sculptures,

flaunting their presence through ornament in the absence of performers, occupy

space less as instruments for producing sound and more like convincing pieces

of wooden furniture.

The ‘Sound Paravan’ series, for example,

consists of upright boards stained in dark hues. These, in turn, are

interlinked with other works such as Dangsankidung (2021)

and Sound Frame (2020), together constructing a

kind of spatiotemporal landscape. But the ensuing performance reclaims this

stilled landscape as a stage, reactivating it and endowing it with another

dimension of narrative–sound. The “paravan” in the background soon becomes the

protagonist, transforming background into foreground, vivifying the landscape.

Turning

our gaze to his organized performances: the exhibition hall begins to vibrate

with sound. The static sculptures function as instruments, regaining life.

Vision, grounded in form and concept, has been the sense most optimized to

construct the rational modernity of the West, for it enables precise

identification, differentiation, and naming. Hearing, by contrast, cannot as

clearly delineate objects, but it allows one to sense beyond the unidirectional

frame of vision, reaching into the invisible. In other words, auditory

experience, lacking the precision of imagery, instead senses environment,

situation, and context beyond the visual frame, bearing the potential to draw

forth expanded narratives outside the fixed systems of perception.

Seo’s

practice thereby unsettles the vision-centered systems, conditions, and

formats, replacing the vanishing of visual illusion with a new sensation that

reverberates across space and time. Moreover, the sound employed is distinctly

grounded in Eastern tonalities. In his work, the East cloaked in sound

overwhelms the West, tradition tears through and protrudes from the

contemporary. The auditory experiences he weaves drift around the visual

phenomena–objects, multiplying interpretive routes and distancing themselves from

fixed preconceptions. The environment before us becomes an auditory-based

condition, a hybrid landscape established atop it. Within this conflated,

hybrid-driven space, we are compelled to reconsider and rearticulate the

coordinates upon which we stand, free of prior orders or systems.

Looking

at his more recent exhibition 《Praise of

Crossbred》 (2023, KimHeeSoo ArtCenter, Seoul), one sees

that he continues to borrow forms such as paravans and tetrapods, suggesting

again the presence of background or boundary surfaces. Yet here, by excluding

the sonic potential emphasized in earlier works, the artist appears intent on

amplifying the imaginative potential of the audience instead. With the

performative act of “playing” the objects withdrawn, the viewer is tasked with

finding interpretive possibilities within the fissures of surface

ornamentation. It could be seen as concentrating instead on the perceptual

properties of the visual medium, appearing almost as if he had discarded the

unique language already established. Yet this too may be understood as part of

an experimental formal inquiry—at times recalling his earlier work, while at

other times attempting to acquire and extend his unique hybrid narratives

through slightly altered approaches.

The

tetrapod-shaped sculptures, such as Monument #01 (2022),

stand with commanding presence in space, appearing like memorials. Towering in

form, their massive black bodies stand as if transcending the finitude of

individual life. Gilded images and texts embroidered across their surfaces lend

further symbolism to these (seeming) monuments. The indecipherable script

imbues them with an aura of mystery. Yet once one learns that the text is based

on the artist’s own intimate personal experiences and merely translated into

Polish—a language unfamiliar to most Korean viewers—the authority of the

monument collapses. The micro-histories effaced in the grand narratives of

official, knowledge- and power-constructed history here paradoxically gain

status, acquiring the power of reversal and subversion precisely through this

monumental gesture.

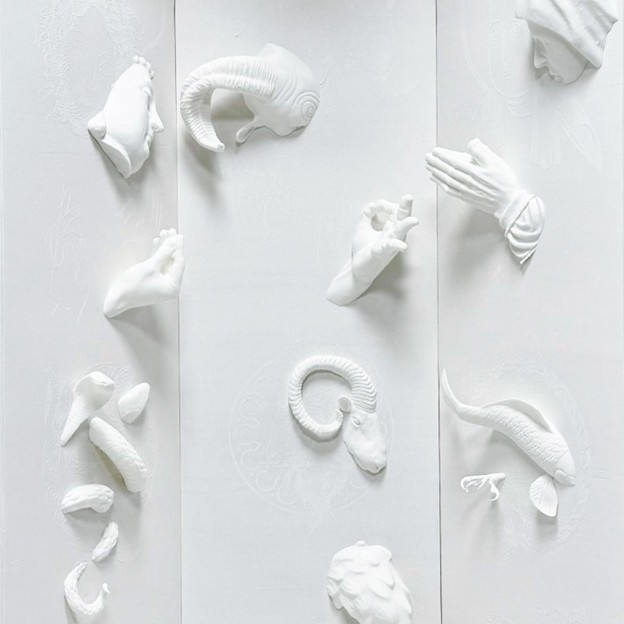

The same is true for the images inscribed on another

monument, Monument #02 (2023). Extracted from

Eastern and Western illustrations and encyclopedia plates, they are stripped

from their original contexts and demoted to images without narrative, placed in

arbitrary order. Spectators, enticed by the clarity of the illustrations, may

seek meaning in them, but these appropriated images are dislodged from symbolic

value, reborn instead as images bearing the potential for subversion and

displacement. While his works may no longer employ instruments, the imagination

grounded in auditory experience is strengthened. The string-bodied forms, or

small paravan-like objects substituted with slender upright speakers, offer

formal cues that invite consistent expectations—of performance, or of

predictable scales.

Viewers, however, are placed in the position of having to

perform their own imagination between these visual traces and the gestures

without resonance. In fact, Seo had previously experimented with sculptural

objects that reacted to audiences in the absence of performance: works embedded

with sensors that responded to visitors’ movements, or instruments placed on a

stage demanding that viewers wander aimlessly and become performers themselves.

Listeners had to follow or imagine the sounds arising, transforming the given

environment into an event. 《Praise of

Crossbred》 is no different. Audiences must newly

perceive the positionality of all beings in the space, imagining different

times for the same place, or different places for the same time, sometimes

linking, sometimes dispersing.

What,

then, constitutes community today? From where do shared identity and belonging

arise? How fictitious are notions like “nation” or “we”? The hybrid landscapes

Seo renders counter the purity sanctioned by the name of “we.” They question

the very purity that has sustained systems to date. He attends to the margins

and undersides outside hierarchical structures, focusing on what has been

deemed impure, deliberately entangling and blending forms in order to fissure

the epistemic frameworks and narratives that have endured uncritically. The

artist states that he seeks to “restore the countless possibilities erased in

the refining process of becoming purebred through methods of representing

hybridity in its mixed state.” For him, hybridity thus prompts a critical

consideration of the narratives, hierarchies, standardizations, and regulations

produced by purity, and of the present conditions shaped thereby.

Footnote

(1)

It may not be crucial what kind of art education the artist received. Yet

recalling Seo’s past career as a furniture designer, it seems only natural that

the external structures of his works resemble the forms of furniture. While

some artists conceal backgrounds divergent from the trajectory of fine art, in

Seo’s case he has aptly absorbed the skills acquired into his own production

methods and, moreover, actively reintroduced them into his formal language for

conceptual operation—a fact worth noting.