If

we follow Rousseau’s lucid premise in Discourse on the Origin and

Basis of Inequality Among Men, then ever since the primal act of

fencing off land, humans have been oriented by the dichotomy of inside and

outside, above and below. Through this orientation, the relationship of

dominator and dominated has become at once exceedingly simple and yet, precisely

for that reason, utterly entrenched. When such a geography of boundaries

transitions into the state of human civilization, the territory within is

referred to as “us,” and the outside as “them.” Boundaries do not merely

demarcate land; within them, both “us” and “them” come to be divided by class,

race, or lineage, thereby producing the body itself as territory. The

boundaries inscribed upon land and the body become narrowed and further

subdivided, eventually converging upon the smallest units of self and other,

“I” and “you.” To become a complete subject as a territory requires a demand

for universality that must be presupposed and achieved.

The

territory of the individual must ceaselessly externalize the internal, while

simultaneously internalizing the external in a repetitive process. This

inevitability of negotiating the particular and the universal, the individual

and the whole, is ultimately tied to the action of a centripetal force of

cohesion. This force is frequently named power, or domination. Sunghyeop Seo’s

practice traverses the black surfaces of the territory’s borders where this

centripetal force of power does not reach. The boundary line, belonging to no

one and to everyone, disrupts the cohesion toward the center. His black

boundary spaces do not possess extension like a line made of successive points,

but rather are drawn like deep fissures between the inside and outside of a geographical

coordinate. This black space is as lucid as it is transparent, disappearing

like a solid ghost. The tetrapod, which appears in Seo’s work, is not marked on

any map, and can be neither land nor sea. It occupies the fissure between power

and domination, between continuity and discontinuity of “I” and “you,” like a

mirage tangled in overlapping layers. Seo himself states of this space:

“The

location of the breakwater is special. The boundary space between sea and water

created by the breakwater transforms at every moment. At one time it is land,

and in an instant it becomes sea. From sea, it soon becomes water. It is empty

yet solid. Solid yet momentary. Momentary yet continuous. These ambivalent

modalities of transformation constitute the capacity of the boundary space. And

so, the boundary space is hybrid.”– From Sunghyeop Seo’s artist note Why the Breakwater?

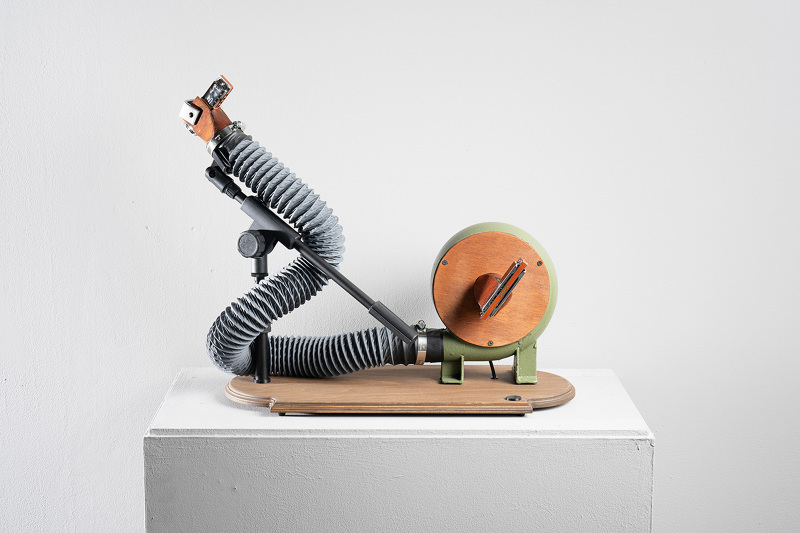

In

2023, Sunghyeop Seo held two solo exhibitions, 《Praise of Crossbred》 at Soorim Museum of Art

and 《Mixed Sublime》 at Art

Space Hyeong. At the Soorim Museum, massive black tetrapod structures were

installed across the grand hall, at times monumental, at times in clustered

formations. Yet before encountering these, the audience first met an array of

massive string instruments lined up in silence. The tightly tuned tension of

the unplayed strings urged audiences to imagine their resonances, splitting the

air into dry monophonic waves. These waves led us to other waves of sound, and

at their culmination stood the colossal tetrapod, Monument #01.

Topped with the Doric capital of an ancient Greek temple, engraved with unknown

alphabetic letters upon its black body, it soared like the Greek architectural

columns that mark the origin of European civilization, yet simultaneously

signified the space of boundaries that can be neither land nor sea. From within

emanated the subdued voice of a man speaking in Polish—a language

incomprehensible to most Korean viewers, perceived as mere murmurings or sound.

When language, the strongest system of culture, collapses into sound devoid of

decipherable meaning, hearing experiences it as waves, free from the material

of signification.

Particularly

in Seo’s work, the tetrapod—stripped of specific cultural function or

meaning—constitutes the boundary space, an interstitial realm that traverses

inside and outside, above and below, left and right, becoming a

multidimensional locus. It is a place where monuments and icons of culture,

sounds and languages, are absorbed into the black line of the boundary and

undergo hybridization. Thus, the boundary space he proposes exists outside the

dominant forces of territorial sovereignty; it belongs nowhere yet can belong

to anything, relating instead to freedom. This deterritorialized boundary,

slipping free from the network of signification of the symbolic order, can

articulate a language liberated from the repression that underpins the

symbolic. It manifests as hybrid signs that slide away from fossilized usages

within the system, and as crossbred images in which ancient myths and folktales

are intermingled.

Within

such a constructed boundary space, the individual discovers the vitality of a

free subject, freed from censored purism and the categorical constraints of

civilization. It resembles a non-space that transcends geographical and

physical conditions, yet unmistakably exists as a de-spatialized space. It is

not an imaginary regression outside the symbolic order, but rather a topology

of the Real that abruptly emerges within the symbolic, appearing as a

silhouette of liberation against the fixed system. Thus, the space can become

land or sea, self or other. Moreover, when these spaces connect and align in

solidarity, a broader boundary space emerges. A Certain

Connection is constructed as an aggregation of tetrapods,

emitting subsonic inaudible frequencies. Without center or hierarchy, they

overlap and accumulate to form a shared geography, resonating with the deep

pulsations of beings stripped of specific meaning. When tetrapods coalesce into

such a shared geography, not as specific places but as sites of hybridity, the

boundary space gains the vital pulse of escape.

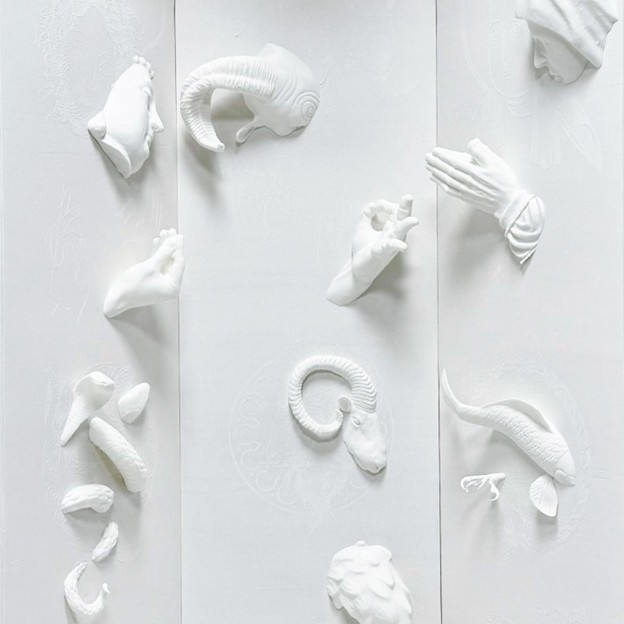

What

Sunghyeop Seo calls the “sublime of hybridity” (Mixed Sublime) emerges from

precisely this life force of mutability and solidarity enacted in practice. It

is the “alcove” of white solidarity, as proposed in Alcove for

White Icon, where the icons of all civilizations are intermingled,

encountered, and prepared to be inscribed with anything. Rather than leaping

over or demolishing walls, it dwells deep within the boundary wall itself,

nullifying both interior and exterior. In such a space, the individual may

become free from the fiction of the Other and the superficiality of the Whole.

Returning once more to Rousseau, we are reminded of the deceit of enclosures—of

constantly seeking validation from others while failing to ask questions of

oneself, of the generalization that comes from externalization. In Seo’s work,

we find the vibrant carnival of individuals transparently traversing such

fences. It is tied to the erosion of ossified conventions and rules through the

deterritorialization of hybridity, and to an attitude of continually

questioning oneself and erasing the fence.