Just

like the mood-lifting pendant, the body’s ultimate local rules can also be

formed in conjunction with devices. In more technical terms, these are

called prostheses. The word comes from Greek, and interestingly, its

original meaning was “to add a syllable at the beginning of a word.” In

English, the term evolved to be used in medicine, meaning “to replace a missing

part of the body with an artificial substitute.” The metaphorical shift from

“adding a syllable” to “adding to the body” is fascinating. Today, prosthesis

discourse has expanded beyond the medical field into various interdisciplinary

studies, producing research under keywords like prosthesis

aesthetics and prosthesis subaltern (Jeon, 2015:17).

Whenever

I think about prostheses, one story comes to mind: the “Riddle of the Sphinx.”

In his remarkable work How Forests Think, Eduardo Kohn re-poses the

Sphinx’s famous question: “What walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at

noon, and three legs in the evening?” As we know, Oedipus answered “human” and

escaped peril. Kohn argues that if “human” is truly the correct answer, it

forces us to fundamentally reconsider what it means to be human.

He writes: “It

reminds us of our two inheritances—our quadrupedal animality and our bipedal

humanity—and of all the ‘canes’ we create and integrate into ourselves to

hobble through our finite lives.” (Kohn, 2018:19)

In

modern thought, a cane was certainly an object, an instrument, something

external. Yet in the Sphinx’s question and Oedipus’s answer, the humanity of

the “three-legged human” already includes the cane. In the orbit of

posthumanist thought, the cane can thus acquire an entirely different

conceptual status. But rather than discussing this in purely discursive terms,

I want to think about the relationship between prostheses and the body in

another way. From the perspective of the enactive body mentioned earlier, how

can the enactment of mind—formed through the materiality of the cane and the

bodily experiences it shapes—be narrated?

Even if we were to analyze the

mechanisms of neuroplasticity, I suspect it would still feel insufficient.

Perhaps this very frustration is why Ito chose to meet people directly and

listen to their most intimate, subtle stories. These days, I have become

increasingly interested in what are called anthropological or ethnographic

research methods. Instead of narratives that blur events, universalize

memories, or abstract experiences, I want to vividly convey the local rules of

the body as they are formed through experiences and events.

At

the end of her prologue, Ito writes: “The

process by which an event with a date gradually loses that date, eventually

forming the body’s uniqueness through local rules; the process by which

experiences both coexist with and do not coexist with memories—in other words,

the eleven narratives through which the body is made—are what I will now

unfold.” (Ito, 22)

I

believe Nayoung Kang understands better than anyone what it means for an event

with a date to gradually lose that date. When I reread this sentence while

writing this text, I could not help but see Kang’s image overlapping with

it—today, too, exchanging a fist bump somewhere. Now, let’s move on to Science

and Technology Studies (STS) and disability studies. STS views science,

technology, society, and culture not as separate domains, but as a totality of

interconnected, complex contexts.

In

everyday conversation, we often use phrases like “That’s very scientific.” When

differing opinions clash, ideas deemed “scientific” are often accorded higher

value. This is likely because science is commonly regarded as objective,

neutral, and context-free—akin to an absolute truth. But STS scholars break

down these assumptions, exposing the power relations involved in the production

of technological knowledge. At one time, I had the opportunity to read widely

among feminist STS scholars. Immersing myself in feminist STS literature was a

transformative experience—I can say my life, perspectives, and thinking changed

entirely. Feminist STS researchers such as Donna Haraway, Sandra Harding, and

Carolyn Merchant—and, as mentioned earlier, Karen Barad—along with Katherine

Hayles, who reconstructed cybernetics theory while warning against the erasure

of embodiment, all stand in this lineage of feminist STS.

In the beginning,

their inquiries often started with questions like, “Why are there so many fewer

women scientists than men?”—critiquing women’s social achievement within

science. Over time, however, their work came to meticulously examine how gender

hierarchies have influenced the formation of technological knowledge. Reading

feminist STS naturally broadens one’s thinking to include issues of race,

gender, and disability. From the perspective of disability studies, STS can

question the medical history that has constructed knowledge about disability in

ableist terms—in other words, viewing disability as a target for correction and

cure. It can also imagine a disability-centered science and technology.

For

example, in Technofeminism, Judy Wajcman points out

that what we call “the social” has been shaped and constrained as much by the

technological as by the social itself (Wajcman, 2009:66). This idea resonates

with the work of STS scholars who argue that material objects and technological

artifacts are socially constructed. I believe these two perspectives are

mutually entangled: society is formed through material objects and

technological artifacts, and those objects and artifacts are themselves socially

constituted. We must avoid discussing the world solely on a discursive level or

understanding it purely in terms of material agency. We need to consider the

full range of complex agencies—human and nonhuman—that have shaped and been

shaped by each other in the processes of formation and composition. So how can

we simultaneously address the linguistic-discursive epistemologies that have

shaped the concept of disability and the agency of nonhuman entities, including

prostheses? Bruno Latour’s Actor–Network Theory might offer some clues here.

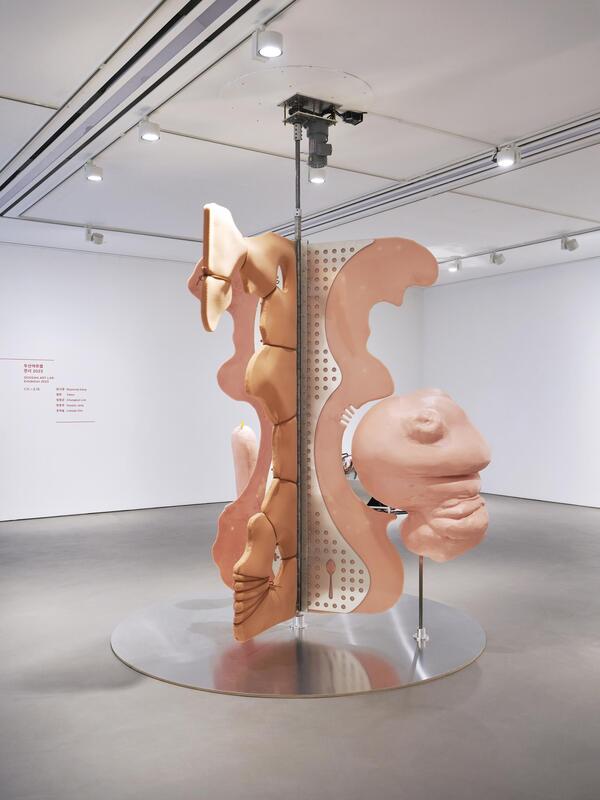

In Becoming

a Cyborg, co-authors Choyeop Kim and Wonyoung Kim introduce the

concept of “crip technoscience.” Kim explains that the Korean equivalent of

“crip” would be “bulgu” (literally “cripple”), a term historically used to

disparage people with disabilities. The term is reclaimed here as an act of

repossessing the power of naming (Kim, 2021:185). Crip technoscience resists

the structure in which disabled people must passively accept the knowledge

outputs produced by nondisabled experts (Kim, 186). Instead, it focuses on how

disabled people, within the specificity of their own embodied experiences, can

reconstruct everyday technologies and reconfigure the world (Kim, 188). Thus,

their declarations are not merely discursive but grounded in concrete

practices. They aim to reconceptualize the narratives of prosthetic

technologies arising from the body of a specific person—not through an ableist,

depoliticized lens, but as tools of disability politics.

Then, what role can

visuality play in this? Vision is a sense endowed with immense power—perhaps

more than any other sensory modality—and is overladen with humanity’s cultural

heritage. If we were to make a leap, we could say that the hegemony of imagery

is condensed into a nondisabled, male-centered literacy. How, then, can we

reclaim that visual hegemony in a way that is anything but naïve? Immersed in

this chain of thought, I can’t help but become industrious—there is so much

work to do. I find myself literally shifting in my seat, spurring myself onward.

This sense of urgency, too, stems from Nayoung Kang’s work and from the

conversation we shared that day. So I ask for your understanding if my words

here have spilled out like water from a broken dam. I did spend days worrying

about whether my words might overwhelm you, but I hope you’ll be able to pick

out a few meaningful threads from this tangled skein. I will end my proposal

here, while looking forward to someday receiving your response—whether in the

exhibition space or in a casual setting, and whether in the form of image,

material, or words. And I hope that, in responding and replying in our own

ways, we will form our own unique rule…

፠Texts cited in this piece are as follows:

Gregory Bateson, trans. Park Dae-sik, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Chaek

Sesang, 2006.

Choyeop Kim & Wonyoung Kim, Becoming a Cyborg, Saegaejeol, 2021.

Michel Foucault, trans. Jung Il-jun, Theories of Power, Saemulgyeol, 1994.

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Korean

trans. Human·Thing·Alliance), Ieum, 2010.

Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think, Sawolui Chaek, 2018.

Asa Ito, trans. Kim Kyung-won, The Remembering Body, Hyunamsa, 2020.

Hye-sook Jeon, Art in the Posthuman Era, Acanet, 2015.

Judy Wajcman, trans. Park Jin-hee & Lee Hyun-sook, Technofeminism,

Kungri, 2009.

Judith Butler, trans. Kim Yoon-sang, Bodies That Matter, Ingan Sarang,

2003.

Katherine Hayles, trans. Heo Jin, How We Became Posthuman, Open Books,

2013.

Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson & Eleanor Rosch, trans. Seok

Bong-rae, The Embodied Mind, Gimmyoung, 2013.

Karen Barad, “Agential Realism,” Meeting the Universe Halfway, Duke

University Press, 2007.

1

I acknowledge my debt to Naso-yeong’s unpublished paper, Foregrounding

the Process of Discursive Practice’s Materialization from a Neurocognitive

Dimension – From the Perspective of Enactive Embodiment, for

clarifying the context and differences between traditional computationalist

cognitive science and second-generation cognitive science.