“I imagine a child who has swallowed up his parents too soon, who frightens himself on that account, 'all by himself,' and, to save himself, rejects and throws up everything that is given to him all gifts, all objects.” - Julia Kristeva, p.27, Powers of Horror

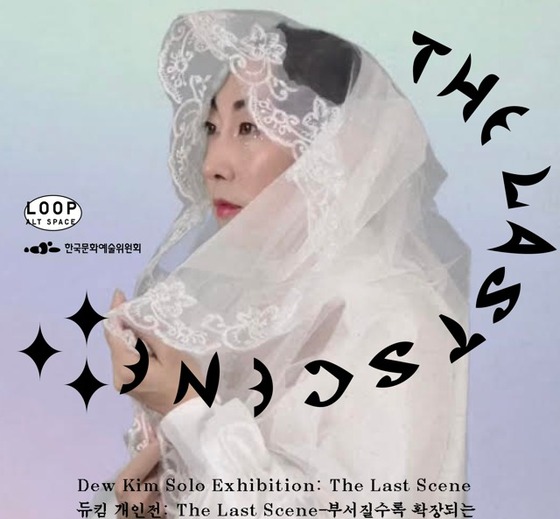

Today, it is not as easy as one may imagine to engage in critical writing on works created by a homosexual artist based on his/her identity. One reason may be that homosexuality, which has become a general term in society, no longer raises as much controversy or repercussions as in the 1970s or 1980s. If we try to find the difficulty of critiques in the social realm, we may point to the characteristics of the Korean society in which we see fast-paced changes occur in contemporary topics or fields all the time. I am quite surprised myself that I have so little to say in my critical writing on the works of a homosexual artist at present, all the more because homosexuality has never been discussed properly in Korea. As I look for possible reasons, I realize that Dew Kim’s works have not really impressed me. I couldn’t feel much emotional impact or find points of empathy.

For example, when faced with the works of Felix Gonzalez T orres, Nicolas Bourriaud defined him as an artist who derived a new aesthetic system not through sight but through empathy. His works transcend the differences in gender identity to correspond to the universal emotion of love. Likewise, the self-narrative of homosexuality is perceived as a process in which the sexual self, or ‘speaking subject’ builds his/her language. Dew Kim also underwent this process. His master’s degree thesis is an autobiographical research paper in which he looks for his own identity generated based on his relationships with his father, a divine subject representing the oppression of Christian doctrines, and his mother, a sole savior. Dionysia, The true story of my relationship with my body, Doujin Kim, Master Thesis, Royal College of Art, 2015

In the thesis, while examining the conflict between his physical urges and pleasures, which he found hard to describe, and his religious faith, he found certain common denominators between the sacred and the secular by analyzing medieval icons and some episodes from the Bible and comparing his private experiences and mythical narratives. In the conclusion, he interpreted the reborn Jesus as a divine masochist. ibid., p. 91

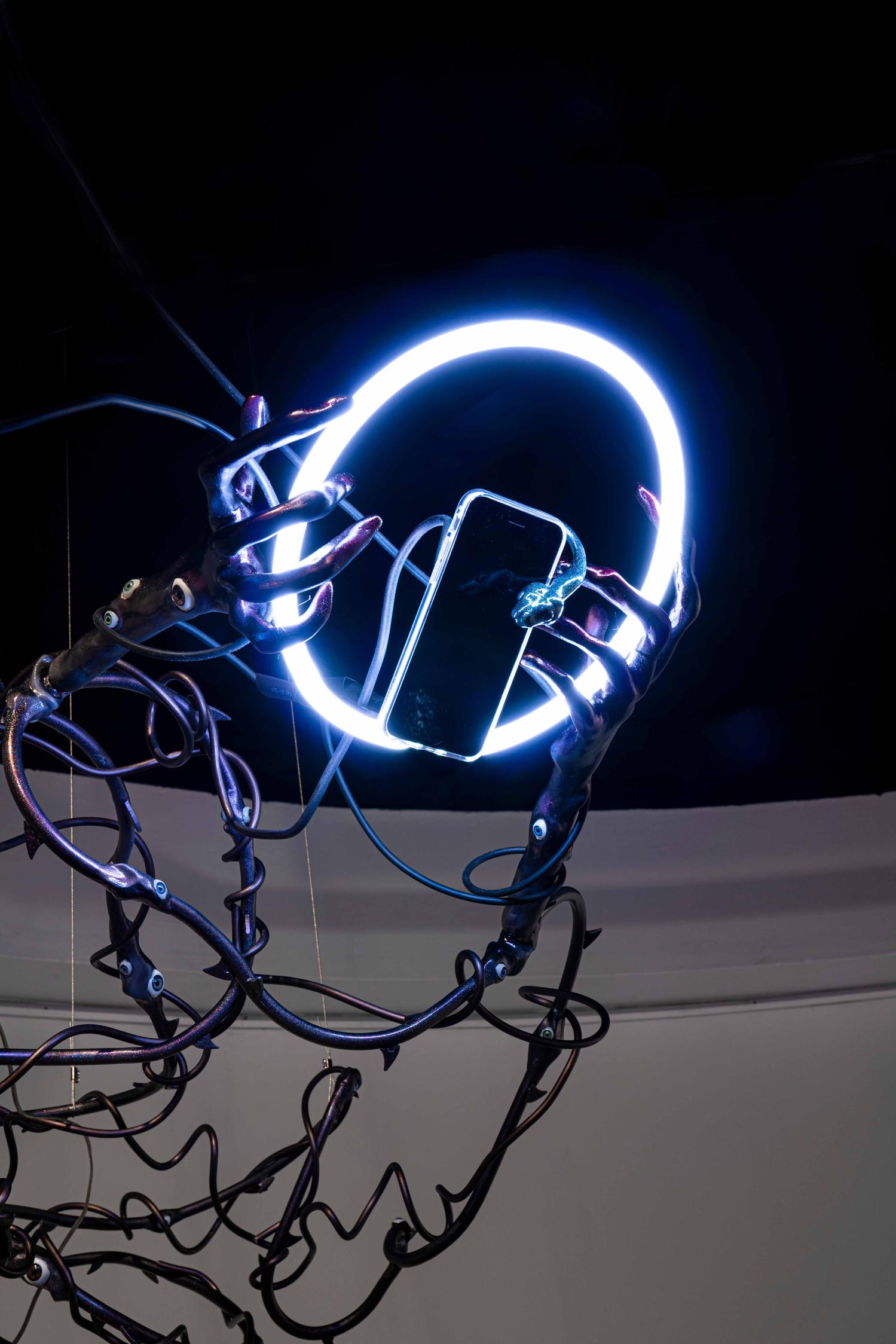

The pain, sacrifice, death, resurrection and eternal life in the Christian resurrection narrative are also found in the works of Gonzalez-Torres. Both the picture that captured his absence through the image of the bed where he had been and the poster image of his thick hand protruding from numerous billboards in different cities suggest the resurrection narrative. Since 2015, Kim has relied on his masochistic inclination as a key driving force behind his works. Subcultural codes such as artificiality, simulacre, absence of impression and playfulness seem to have something in common with the theatricality of masochism.

Therefore, his works have focused on the investigation of how he could implement a mode of being through his sexual pleasures rather than general contemplation on his gender identity. Above all, the first clue for interpreting his works is to understand the artist’s situation where he is suffering considerable psychological pain from the symbol of a father dominating over him, due to his patriarchal father and Christian lifestyle.

Masochism

The process in which an individual discovers and acknowledges ‘oneself’ as a homosexual is a period of paradox where self-denial and formation of self become interwoven, and where one disintegrates and reconstructs oneself. Concerning this process, the artist says that he did not suffer much as a social other, as often found in generalized queer discourses. Instead, his suffering brought by religious faith, which rules over his family, is still going on. He means that due to his peculiarity, he has been recognized as a female-like individual in the heterosexual society. If I interpret this experience roughly, Dew Kim seems to have undergone less gender trouble in his social relationships because he has been treated like a woman. A series of episodes he recalled suggested that the confrontation between nature and artificiality did not result in controversy but naturally formed his identity. He mentioned his memory of a photograph taken in his childhood by his mother, in which she dressed him like a girl. He says that it is still one of her favorite pictures. ibid., p. 23

The reason for Kim’s free alternation of gender roles seems likely to be the gratification of sexual pleasure rather than his early gender experiences. To him, the biological and physical gender differences do not matter much. What is important for him in his sexual love is his quest for masochism enjoyed in theatrical situations he set up with his partner. Here, the masochism deviates the relata of sex and love, and is focused on the implementation of their different roles in sexual intercourse as a theatrical situation. In the practice of masochism, theatricality does not only mean the pleasure gained after the endurance of suffering. It appears that what’s important is the process, and the practice of masochism starts as the participants assume their roles. The roles of dominator and dominated create a certain power structure and draw theatrical experiences in which one becomes the absolute being and the other becomes the victim. Although this theatrical structure seems to represent a typical hierarchy of dominator and dominated, actually the dominated is the subject who produces the dominator, and this is the subversion of masochism, according to Nick Mansfield, a cultural theorist.

Thus, the exhibition title of 《Fire and Faggot》 suggests both treacherous sexual impulses and pleasure felt through punishment and imagination of the future that will arrive after the endurance of suffering, in addition to the interpretation of subjects as victims being punished under Christian doctrines. The narrative of 《Fire and Faggot》 unravels as follows: Oppression of homosexuality from the Christian perspective; intervention of the sorcery of Korean folk religion; struggle between the symbols of two different genres, icons in medieval art and Bujeok, Korean talisman whose origin can hardly be found; and Ttongkkochung Ttongkkochung is a term for demeaning a male homosexual and corresponds to faggot in English. Naturally, here the word was used to disparage oneself. In this exhibition, Dew Kim presents stages in which a lowly being is sublimated into a pure being, a new extended race or tribe of queer people reborn through the rite of fire and embarking on a voyage for their colony.

Absence of impression

As noted above, 《Fire and Faggot》 implies the structure of the Christian mythology quite roughly. The image that reminds of sublimated victims, borrowed from medieval scenes in which people who committed sodomy were burnt at the stake, is full of red flames (Welcome, 2019). Kim interprets this scene through the frame of martyrdom. The victims who became sacrificial offerings are queers Queer here transcends the meaning represented by the acronym of LGBTQ and “Representation by the queer of political interests of certain sexual groups or self-recognition as a minority group asking for the tolerance of the society are denied, and complete resistance not only to ‘heterosexuality’ but to the system of everything ‘normal’ is pursued.” (Extracted from Queer Theory: Sad Native Language, pages 57~58, Culture and Society Vol.13, Nov. 2012). The paper asks whether the study of homosexuality in Korea is focused more on knowledge or the will to live.

Serving the god Anus, and their martyrdom is interconnected with the birth of a new religious faith. The readers must have noticed that HornyHoneydew, the fake religion created by Dew Kim, has an emblem created based on the images of the pelvis and anus. The idea of denying one’s father and serving the impersonal organ of anus is an entirely subversive abjection.

“Abjection accompanies all religious structurings and reappears, to be worked out in a new guise, at the time of their collapse. Several structurations of abjection should be distinguished, each one determining a specific form of the sacred.” Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, page 42, translated into Korean and published by Dongmunson, 2001.

Abjection slides off from its body and loses it. In other words, it experiences catharsis from purification by the sacred, and this is the point that coincides with masochistic practice.

“The question remains as to the ordeal, a secular one this time, that abjection can constitute for someone who, in what is termed knowledge of castration, turning away from perverse dodges, presents himself with his own body and ego as the most precious non-objects; they are no longer seen in their own right but forfeited, abject. The termination of analysis can lead us there, as we shall see. Such are the pangs and delights of masochism.” ibid., page 27, 2001

This is the reason I couldn’t feel any impression from Kim’s works. His works exist only as symbols and surfaces. It is because masochist aesthetics meets the sublime, which is a condition that cannot be measured through reason/emotion. The imagery generated as tedious mechanic repetitions and recombination often seen in contemporary art, production process in which psychological conditions or emotions are suppressed as much as possible, etc., is mingled into digital visual culture to lead to the emergence of another type of aesthetics of sublimity. Now, it may be possible to interpret Kim’s works from the perspective of fetishism. Hal Foster once interpreted surrealism and machines from the Marxist viewpoint, and insisted that the capitalist system makes the product and the producer resemble each other.

Such fetishism is also a mode of being for masochism. This way, Dew Kim imagines the world of the queer located at the boundary of all binary oppositions, neither man nor woman, and neither human, nor object, nor nature. Dew Kim calls this utopia Latrinxia, a planet whose name was derived from lavtrina, a latin word meaning bath or purification. Here, Ttongkko-Chungs are no longer beings of two divided sexes, but are sexless and beyond sex, always in their pure and ideal state of being. They use light energy for metamorphosis and breeding. TtongkkoChungs are an epiphany of a new humanity, living in a utopian world beyond sexes and sexual divisions. The future that he imagines is a world where the social structure does not exist, which is made of only religious simulacre.

It’s not easy to imagine a world consisting of just outer layers, excluding all structures and organs. What can the artist say through a world made of the hyperreal only, without any foundation of criticism? Kristeva interprets the practice of writing descending toward the origin of literature as an act of looking back on the meaning of the speaking subject. The return to the origin, and the construct of an ideal world, may not be concluded as an escapist utopia by Kim. Practices that keep on exploring how the world, which has not been completed, can be formed, represent writing to Kristeva, and the reason is because this is the only way we can avoid the inertia of the dichotomous culture producing differences.