These

elements are offset, however, by the exhibition’s overriding, and at times

unsettling, playfulness and irreverence. Notably, the garish colours of the

figurines make them appear at once jubilant and excessive, even cloying. The

figurine of Jesus, for example, appears camped up, sporting a blonde beard,

bright pink hair, and tacky, sparkling robes stoned with gold (Fig. 17).

Similarly, Bambi is provocatively positioned with its rear in the air and

looking coquettishly behind (Fig. 18). The appearance of similar images and

plastic materials elsewhere in the exhibition yokes these figurines more

closely to queer cultures and countersexual practices.

Notably, Bambi also

appears on the polyvinyl hanging (Fig. 19), nestled among a photograph of

buttocks (Fig. 20) and images that are resonant of transnational,

intra-regional queer popular and media cultures in East Asia, including

queer-coded characters from Japanese anime popular among queer viewers in South

Korea since the 90s, such as Kaworu Nagisa from the post-apocalyptic

series ‘Evangelion’ (Fig. 21) and Sailor Uranus from ‘Sailor

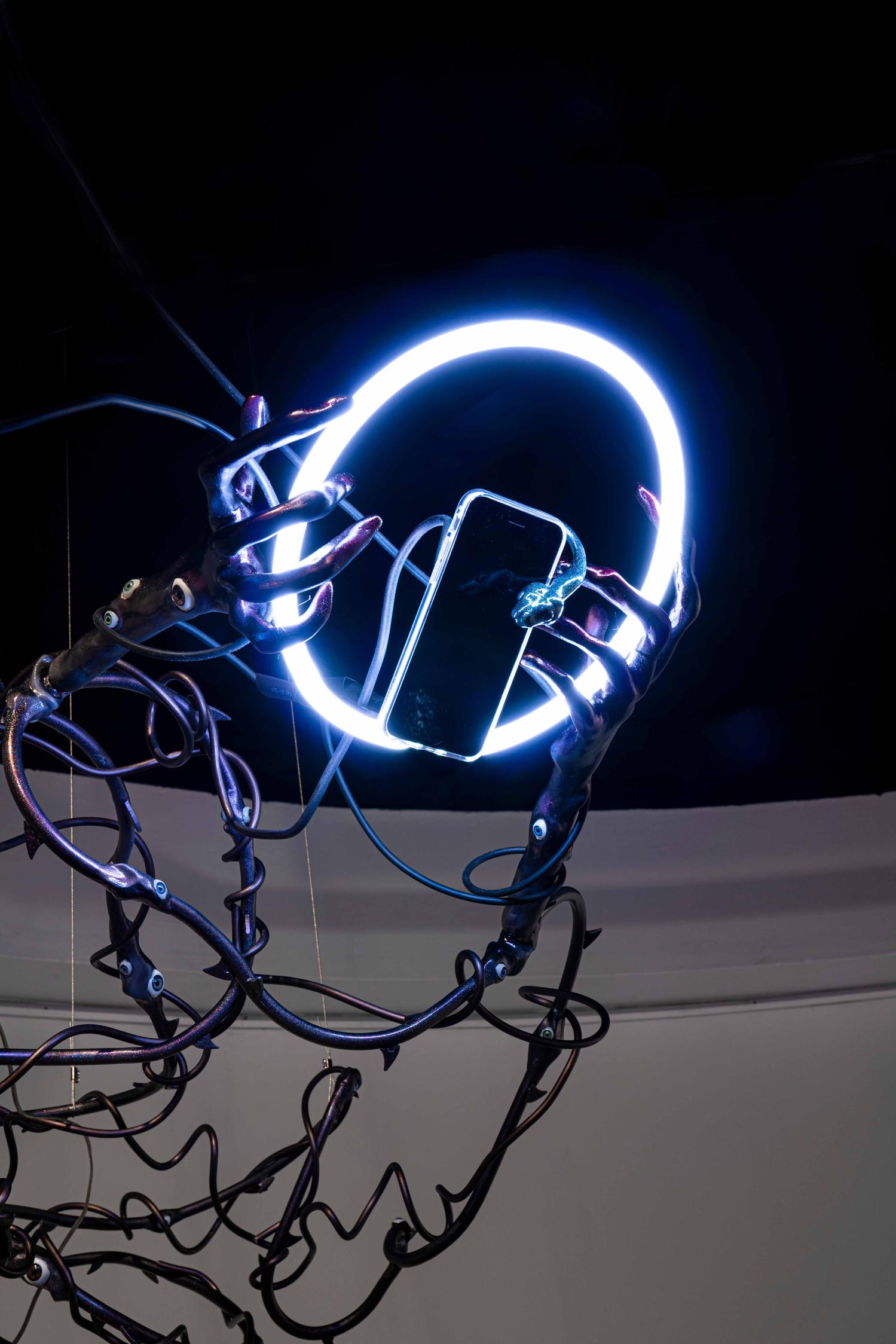

Moon’ (Fig. 22).67 Similarly, in the landscape sculpture,

the zombified hand contrasts with the jubilance of the sedimented layers of

gaudy polyurethane foam (Fig. 1). The video depicting a figure cruising naked

in a countersexual paradise is also embedded in this chaotic, tawdry landscape,

redoubling its affective ambiguity.

To

my mind, this jubilance is a call to embrace the porosity of the human body and

its enmeshment with more-than-human worlds as described by Davis, Schaag, and

others.68 Davis and Schaag, in particular, are quick to

question the ethics of this position even as they tentatively espouse it, and

rightly so: under the current conditions of toxicity and pollution,

economically privileged, white inhabitants of the Global North remain the least

affected.69 Indeed, 《Succulent Humans》 pictures humanity at

the moment of its escape and transformation, and in so doing, it does not

attend to the painful reality of the ‘slow violence’ of ecological destruction

that many of the earth’s species, and humans, are already facing.70 Any

call to embrace porosity should take account of the already existing

disparities in embodied experiences of porosity, which are broadly

differentiated along the lines of class, race, and geography. These disparities

are not, it should be said, accounted for in the utopia plotted in 《Succulent Humans》, in which there is no

longer a need to accommodate sexual or racial difference because it no longer

exists: each succulent human appears the same.

《Succulent Humans》 does, however, invite

us to take pleasure in porosity. As Seymour notes, the mobilisation of affects

of pleasure, irreverence, and irony may open more productive avenues for

engaging with environmental crises compared to guilt and shame.71 The

exhibition invites us, too, to ask how porosity might be placed in the service

of a radical politics. It tethers the respective biological and social ‘toxins’

of plastic and queerness, and suggests that a future that is more hospitable to

the lives of non-human and queer others may lie in an alternative

conception of the human body and of toxicity itself. Citing Ed Cohen, Mel Y.

Chen writes that toxicity is generally ‘understood as an unnaturally external

force that violates (rather than informs) an integral and bounded self’.72 Yet

toxicity also, Davis surmises, ‘forces us to reveal the ways in which we are

multiply composed—of plastic, of toxins, of queer morphologies’.73 This

revelation goes against the heteronormative, masculinist assumption that the

body, and in particular the body sexed as male, is inviolable.

It also

contradicts the ‘bellicose antagonism’ that fuels the insistence of separation

between self and world, between body and its environment.74 An

acceptance of the human body’s porosity entails an acknowledgement of, on the

one hand, its various orifices and capacities for pleasure and existence

outside of heterosexual reproduction; and, on the other, the body’s integral

relation to its environment, including the toxins released into the environment

by human industrial activity and a wilful ignorance of our own porosity. At the

very least, Chen writes, ‘[a]n uptake, rather than a denial of, toxicity seems

to have the power to turn a lens on the anxieties that produce it’.75 An

attention to queer morphologies and to porosity may, as Davis and Schaag tell

us, also form the grounds for practices of care that extend not only to queer

subjects but also to the various forms of life—human and nonhuman—precluded,

begotten, or destroyed by conditions of environmental toxicity.76

《Succulent Humans》, finally, asks after the

queer ecological potential of considering not just the porosity but also

the plasticity of the body, its capacity for transformation and

mutation even as it might, like plastic, hold temporary form.77 Pertinent

here is the exhibition’s playful subversion of tropes associated with

ecohorror. Christy Tidwell writes that ecohorror as a genre ‘deals with our

fears and anxieties about the environment’.78 Usually it

involves an encounter with the nonhuman, which is horrifying because it is

‘inexplicable, irrational, and implacable’.79 In their

introduction to a series of articles about ecohorror in ‘Interdisciplinary

Studies in Literature and Environment (ISLE)’, Stephen Rust and Carter

Soles propose an expanded definition of ecohorror beyond the limits of a genre,

a definition which ‘includes analyses of texts in which horrific texts and

tropes are used to promote ecological awareness, represent ecological crises,

or blur human/non-human distinctions more broadly’.80 They add

that ecohorror ‘assumes that environmental disruption is haunting humanity’s

relationship to the non-human world’.81 In 《Succulent Humans》, the idea of the

plant-human hybrid is reminiscent of eco-horror narratives such as John

Wyndham’s post-apocalyptic novel ‘The Day of the Triffids’ (1951), in

which a sentient, alien carnivorous plant species begins killing humans and

proliferating across the world, or the film ‘Annihilation’ (2018,

adapted from a 2014 novel by Jeff VanderMeer), in which human and animal bodies

mutate and become plant-like owing to an extraterrestrial intelligence.82

What

is unsettling about 《Succulent

Humans》 is precisely its playful invitation not to

give in to apocalyptic fantasies of our complete non-being, and instead to

imagine a future that sees the survival of a form of human life that is also

somehow botanical. As in Octavia Butler’s ‘Xenogenesis’ series

(1987–89), in which the human survivors of a nuclear disaster must either

reproduce with betentacled alien beings for the sake of both species or else

accept extinction, the last surviving humans of the exhibition’s story choose

to become vegetal. Living like a plant, Michael Marder offers, entails

‘welcoming the other, forming a rhizome with it, and turning oneself into the

passage for the other without violating it or dominating it’.83 This

rhizomatic existence not only disrupts staid but enduring conceptions of nature

as never changing, or as having an idealised, pure form sullied by human

interference and to which it must be returned.84 It also

explains, I think, the artificiality of the plants hanging in the exhibition

space: coated in a plastic-looking membrane, it is as if these succulent human

beings have found a way to adapt by merging with, or acting as a passage for,

the plastics and pollutants which, according to the exhibition’s narrative,

have flooded the earth. These plastic, test-tube succulents, moreover,

represent a strange and queer ecology that transcends the limits of total human

understanding or control.

On

this point, it is apt to return, once more, to the cruising figure glimpsed

in A Succulent Human. Though the figure wanders around a forest, the video

depicting its perambulations is embedded in the form of a synthetic landmass,

drawing the forest and the artificial landmass into a generative friction,

suggestive of the strange, new, flourishing forms of more-than-human life and

enmeshment evoked elsewhere in the exhibition and in its narrative. Indeed, as

well as evoking a nonhuman gaze, the distortions through which the images of

the forest are filtered recalls the undulations of the landscape sculpture.

Jayna Brown writes of the ‘new forms of sociality and modes of being’ opened up

by the practice of estranging ourselves from ‘the life of our species’ and

engaging, instead, with the ‘plasticity of life’ occurring even at the cellular

level.85 We might, then, see the figure in A Succulent

Human as cruising for untold and unknown forms of more-than-human

sociality, for what Benjamin Dalton calls a kind of ‘queerness-without-us’, a

porous, plastic, and entangled existence that continues beyond life as we know

it.86

Conclusion: Queer Utopias, Monstrous Futures

In ‘Queer

Phenomenology’ (2006), Sara Ahmed cautions against ‘idealiz[ing] queer

worlds or simply locat[ing] them in an alternative space’, because ‘what is

queer is never, after all, exterior to its object’.87 In their

invocation of science fiction and utopia, the works examined in this chapter

might literally appear to locate queer worlds in another space and time; after

all, the genre has long suffered charges of escapism and frivolity. Yet science

fiction worlds can indeed tell us about the world that is presently ‘in place’,

to use Ahmed’s phrase. Braidotti writes that while science fiction

representations appear oriented towards a fanciful future, they act as

fantastical social imaginaries about modernity.88

Likewise,

Ursula Le Guin writes that ‘science fiction properly conceived … is a way of

describing what is actually going on’.89 And for Ramzi Fawaz,

the ‘encounters with figures of radical otherness’ engendered in fantasy worlds

‘provide tools to subvert dominant systems of power and reorient one’s ethical

investments towards bodies, objects, and worldviews formerly dismissed as alien

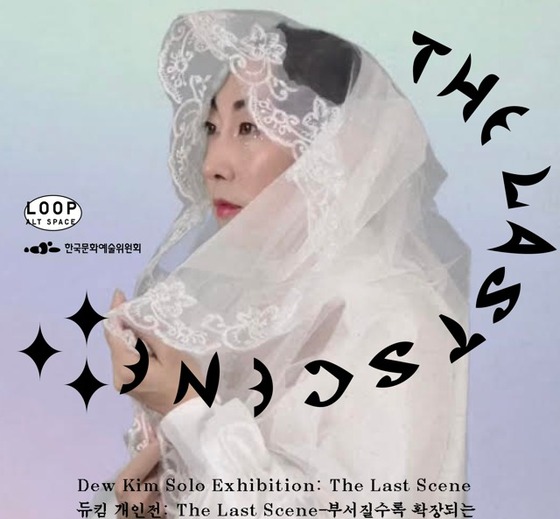

to the self’.90 What precisely, then, can we draw from the

world dreamt up in Dew Kim’s 《Succulent Humans》? What does it have to tell

us about the worlds already ‘in place’, about the futures these worlds are

oriented towards, and about alternative orientations and futures that might be

possible?

On

the one hand, Kim’s works accommodate the viewer to a future that is, to quote

Jacques Derrida, ‘necessarily monstrous’. Derrida explains that

the

figure of the future, that is, that which can only be surprising, that for

which we are not prepared, you see, is heralded by species of monsters. A

future that would not be monstrous would not be a future; it would already be a

predictable, calculable, and programmable tomorrow. All experience open to the

future is prepared or prepares itself to welcome the monstrous arrivant.91

The

future glimpsed in 《Succulent

Humans》 may appear monstrous precisely because it

attests to the futility of clinging to fantasies of reproductive futurism and

offers alternative fantasies of life-to-come. The exhibition’s orgy of plastic

underscores that the reproduction of the social and biological order arranged

by capitalism cannot continue in perpetuity, for, as we have seen, capitalism

is destroying the ecological conditions for its own subsistence. Moreover, the

altered levels of toxicity brought about by capitalism and industrial activity

are queering our bodies, whether we like it or not. The notion of the body as

independent, discrete, and bounded, as well as fantasies of a ‘future perfect’

in which this notion is sustained (as in the homophobic statements with which

this chapter began), cannot account for these actualities.

Rather

than the reproduction of sameness, survival, whatever it entails, will

necessarily involve transformation—the unspooling of this order rather than its

indefatigable continuation. Notably, survival-as-adaptation and -transformation

are an altogether different kind from the survival-as-conquest that

characterises many science fiction blockbuster films and, increasingly,

entrepreneurial framings of space exploration.92 Instead of

conquering, domesticating, or eradicating monstrous and non-human others, 《Succulent Humans》 invites us instead to

draw closer to these others and to become intimate with them, in part through a

recognition of our own bodily porosity and already-existing enmeshment. For

Davis, embracing an ethics of porosity and permeability might open onto greater

attention and hospitality towards others, both our ‘non-filial human progeny’

and the ‘new bacterial communities’ and ‘plasticized, microbial progeny’

produced by conditions of toxicity.93

Yet, as I have argued, by

imagining future humans that are at once succulent and synthetic, the

exhibition goes beyond Davis’s position and encourages us to recognise our

own plasticity, as well: that is, the ‘biological plasticity of living

organisms’ and ‘the capacity to adapt and change’, as Schaag puts it.94 《Succulent Humans》 suggests that we

might take pleasure in this plasticity. It articulates a more hospitable

orientation to an unknowable future populated by radical others and invites us

to be open to becoming radically other ourselves. A hospitality to monstrous

futures might also facilitate hospitality to those framed as monstrous others

in the present, too—to those who do not conform to constructed boundaries of

normativity and their ideals.

《Succulent Humans》 also reminds us that

the reproduction of the social and biological order also entails the

foreclosure of the possibility of other orders and other lives. In this way,

the exhibition evokes the necropolitical—the consigning of certain populations

to physical and social death—as much as the biopolitical, or the governing of

life.95 Following a reading of Butler’s ‘Xenogenesis’ trilogy,

Neel Ahuja tells us that

reproduction

is at once a negation and transition, and that the living incorporate extinct

lives that could have been. At the heart of the body and the future lies the

corpse.96

Similarly,

in her analysis of waste in contemporary art, Boetzkes calls for us to think of

waste ‘as a systemic pattern of creating the world through the foreclosure

of life and diversity’.97 In other words, if ‘life’ and

‘success’ are understood as the reproduction and perfection of the existing

social and biological order, then life always entails the deaths of other

beings, human and non-human, who are excluded from this order, and success

always entails failure: the failure of other beings to survive or thrive. The

future is not a question of utopia versus apocalypse; one person’s utopia is

another person’s apocalypse, as conservative, Protestant responses to LGBTQ+

activism in Korea make clear. However, as the works examined in this chapter

suggest, we might yet learn another language of the body, attune ourselves to

its porosity and plasticity, and bring human and non-human others into our

present and into our visions for the future. Only then might we move beyond

fatalistic narratives of ‘life’ and ‘death’, ‘success’ or ‘failure’, or ‘us’

versus ‘them’, as well as binaries of open, porous, and contaminated bodies

versus closed, contained, uncontaminated ones. Life will go on; it just may not

be human.