Articles

[Review] 《The Weaponocene Epoch》(Seoul National University Museum of Art, Feb 6–May 4, 2025)

February 06, 2025

Lee Nayeon | Independent curator

《무기세》 전시 전경 (서울대학교미술관,

2025) © 서울대학교

《무기세》 전시 전경 (서울대학교미술관,

2025) © 서울대학교

From instruments of control to objects of thought

Paul Virilio argued that modern technology cannot be separated from military

purposes. Through his concept of “pure war,” he suggested that the boundary

between war and peace has disappeared in contemporary society. In other words,

even times of peace function as preparations for the next war, meaning that a

state of war continues without end. According to Virilio, technological

development is directly linked to the arms race, and technology itself becomes

an invisible war waged against humans—a weapon in its own right. Modes of

transportation, communication, and visual technology all evolved from military

needs, ultimately reorganizing social structure and order along military logic.

He criticized this techno-military complex for dominating modern society,

taking precedence over politics and ethics. In his view, contemporary

technology no longer operates as a simple tool but functions as a weaponized

force that shapes and maintains sociopolitical and economic structures.

The exhibition 《The Weaponocene Epoch》(2025) at the Seoul

National University Museum of Art seems to skillfully translate Virilio’s

insights into the language of art. The term “Weaponocene” extends beyond

“Anthropocene” and “Capitalocene” to denote an era dominated by weapons.

Curated by Sim Sangyong, the exhibition explores the impact of weapons on

modern life through art while seeking possibilities for rupturing the logic of

violence. The works illustrate how weapons have moved beyond the

battlefield—now influencing corporate competition, media consumption, and

technological development.

The exhibition unfolds in three sections. The first, “Militarized

Everyday Life,” explores how weapons have infiltrated daily routines. Heobori’s

installation features tanks and guns made from neckties and business suit

fabrics, symbolizing the fusion of capitalism and military order. This suggests

that economic competition in today’s society may be no different from military

structure—perhaps wearing a suit to work isn’t so different from donning armor

for the battlefield. Kang Hong Goo’s photographs capture military traces hidden

in mundane cityscapes. Fighter jets crossing the sky and warships anchored in

the sea remind us that military power is deeply embedded in everyday life. An

Sung Seok’s sound installation repeatedly plays a military wake-up alarm. Based

on his experience witnessing comrades’ deaths during his service as an army

photographer, the work memorializes the innocent soldiers lost.

The second section, “Weapon as Spectacle,” investigates how

weapons are visually consumed in media and art. Choi Jaehun’s performance

documentation shows a gun being fired at reflective stainless-steel plates,

leaving visible bullet marks that symbolize the self-destructive nature of

violence. Viewers see their reflections overlaid with the scars of bullets,

experiencing the paradox that violence ultimately returns to oneself. Noh

Younghoon’s all-white works satirize the consumption of violent imagery as entertainment,

featuring Disney-style gas masks and landmines shaped like balloons. These

recreate WWII-era children’s gas masks and critique how war’s terror is

transformed into titillating content in films, games, and news, thereby

distorting the essence of violence. Lee Yongbaek’s photographic works portray

soldiers in camouflage within peaceful flower gardens, hinting that even

seemingly safe spaces are covertly governed by military logic. The works

visualize how violence has become part of everyday life.

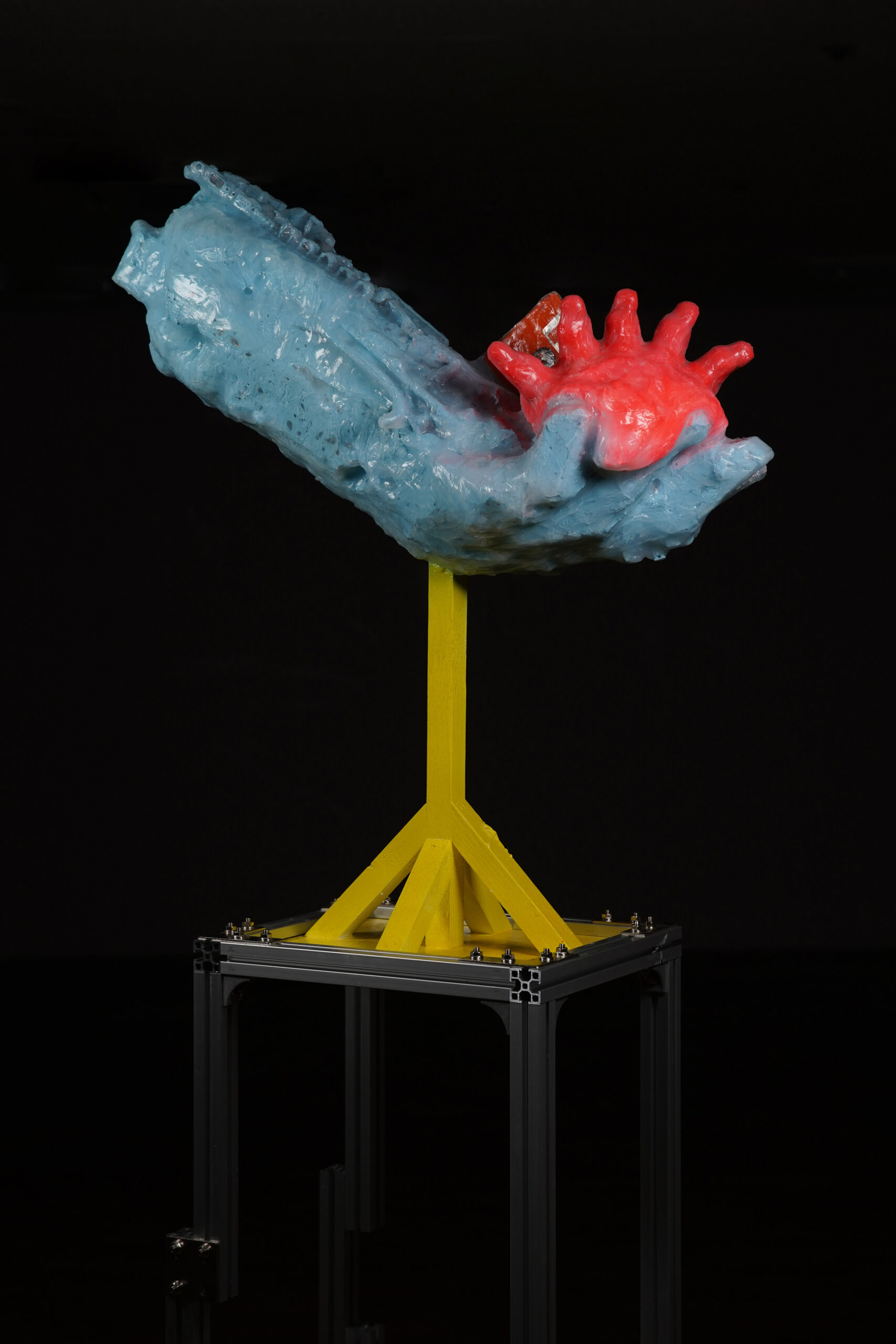

《무기세》 전시 전경 (서울대학교미술관,

2025) © 서울대학교

《무기세》 전시 전경 (서울대학교미술관,

2025) © 서울대학교

The third section, “Weapons, Familiar Futures,” warns of a future

shaped by the expanding influence of weapons into environmental and

technological realms. Ha Tae-beom’s photographs recreate scenes from the Syrian

Civil War as white models—devoid of blood or cries, revealing only desolate ruins.

By presenting war scenes poetically, he critiques how images of war are

aestheticized and consumed in the media. Rather than showing actual war photos,

he recreates them in a filtered form, provoking meta-reflection on the image

itself. Oh Jeisung’s sculpture portrays memories passed down from father to

grandfather to great-grandfather, lined up like soldiers marching off to war—an

image that resonates eerily. Bang Jung-a’s paintings combine imagery of nuclear

power plants with zombies, warning of a future where technological and violent

control merge to threaten humanity. She reveals nuclear facilities absent from

maps due to military secrecy, alongside zombie forms.

《The Weaponocene Epoch》

exposes how weapons function not merely as tools of war but as systems that

shape and enforce social order. Weapons are no longer limited to guns and

swords on the battlefield—they permeate capitalist competition, technological

progress, and media consumption. Heobori’s fabric tank reveals the connection

between military and economic systems, while Noh Younghoon’s gas masks

illustrate how images of violence are commodified. Oh Jeisung’s ruins make

visible the environmental destruction wrought by weaponry. The logic of weapons

merges with capitalist competition, technological development, and systems of

power, internalizing violent order into everyday life.

Yet, the exhibition also proposes the potential for art to

overturn this logic. Just as Heobori’s tank is made from fabric, tools of

violence can be dismantled symbolically. Choi Jaehun’s mirrored performance

reveals the cyclical nature of violence, showing how art can visualize and

subvert violent structures. Curator Sim Sangyong notes that the nations leading

in weapon production and export also dominate contemporary art discourse,

emphasizing that art must not only critique weapons but rupture weaponized ways

of thinking. Ultimately, the exhibition proposes the transformative power of

art as a force beyond weaponized systems—inviting viewers to reimagine and seek

out humanity and peace.