The True Landscape of Cultural Syncretism and the New Signs of

Character-Drawings: Landscape of eight views of Dadaepo and Their

Characters

Minseok

Chi’s exhibition Landscape of eight views of Dadaepo and Their

Characters delivers an incredible amount of work and speed, hard

to believe as the result of only a three-month residency at the Hongti Art

Center. Such productivity was possible because the artist’s internalized world

had already infiltrated the natural environment, history, and legends

surrounding Dadaepo. Fundamentally, the artist reinterprets the core of

shamanism through the lens of post-fetishism. Whether in shaman paintings,

ritual implements, talismans, or characters, Chi remaps the original shamanistic

codes—intensely culturized stamps or divine seals—into new cultural

expressions. These “seal effects” or “divine seal effects” are precisely the

magical outcomes sought by shamanism. Fetishism in this context represents the

shamanistic strategy for materializing such magic.

According

to Marx, fetishism, as the idolization of money born from commodity exchange in

capitalism, is a superstition to be overcome. This superstition becomes a

religion for economic animals living within capitalism. Whether one sees this

as religion or ideology determines if the money-fetish can be dismantled. Marx

believed that, as ideology, it could be overcome. However, capitalism,

continuing in its undead state, has not shaken off the money-fetish and still

persists. This fetishism, in the sense that it is “dead but functioning,” is

indeed cynical—disbelieved yet followed for its petty efficacy.

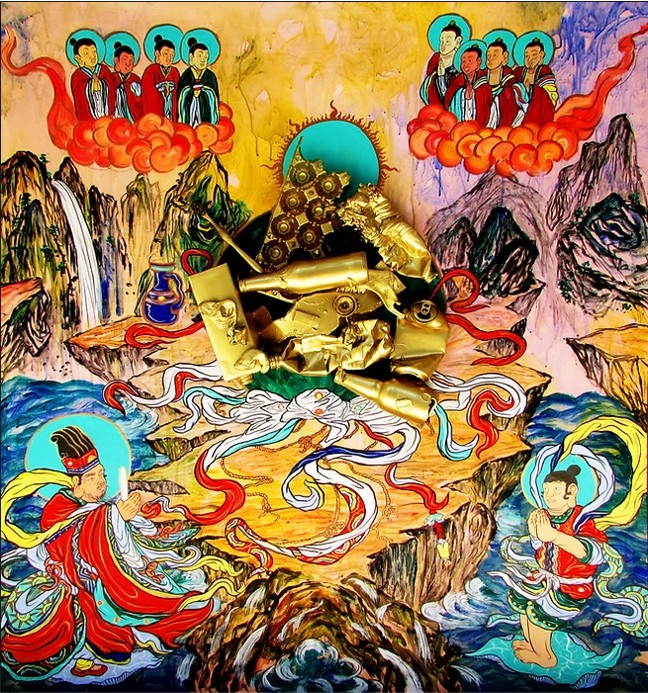

Minseok

Chi’s work of absorbing Dadaepo’s landscape into his character-drawing schema,

as though he were Cangjie 蒼頡—the legendary

inventor of Chinese characters—is not a symbolic rendering of the so-called

“Eight Scenic Views of Dadaepo.” Rather, he attempts to remap the sticky and

solid world of land spirits, local ghosts, and territorial gods residing within

those landscapes into his character drawings. This cultural remapping aims to

stamp new seals onto areas previously fixed and protected by existing territorial

frameworks, transitioning them into new divine domains. In the Avatamsaka

Sutra, this transition toward a new divine realm is described as

“Ocean Seal Samādhi,” a meditative state where each

crashing wave of the ocean imprints the seal of life.

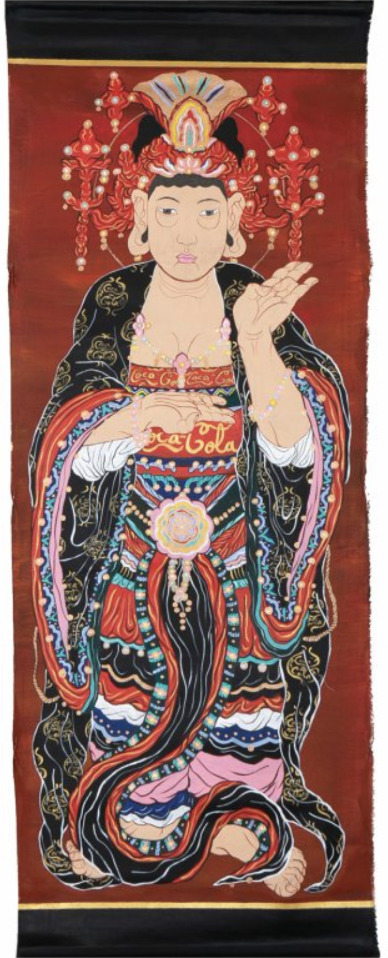

Chi’s

prior works—such as the arrangement of various shamanic spirits and the

invention of a Coca-Cola deity—may seem familiar within the code of shamanism.

But in truth, that familiarity is the bait leading one into samādhi. The schema of “landscape + character-drawing” transforms landscapes into symbolic units of fetishism. Like

personal talismans meant for peace and safety, the works become platforms for

shamanic rituals—for

instance, “good

fortune rituals to make the rich richer” or “great

general rituals to release spirits fixed to the land and return them to their

celestial origins.” Chi’s intention is not to create monumental paintings or

shamanistic representations of famous Dadaepo landmarks. Instead, his project

is an effort to advocate for a post-fetishism—a new type of fetish that

counters, and thereby transcends, the existing money-fetish.

“Which

general is my general, which general is mine!

Is it not my general who is full of greed and desire?

One front leg kicks, the other pulls, blocking the sunny hillside

What is this? Do you call this your altar?”

—

From 〈Taryeong of the General〉

In

this verse, fetishism begins with gluttony and ends with a barked demand for

wealth. Lacking negotiations or gift exchanges, people lament being trapped in

poverty and hunger. The general spirit, realizing this, repents and says, “I

will accept your small sincerity as great sincerity and grant you blessings and

fortune.” Confronted with the money-fetish, the general spirit responds to the

shameless demands of the wealthy not by reinforcing his role as land guardian

but by returning to the celestial realm with infinite giving power. Thus, the

entrenched landlords, stingy misers, and territorial oligarchs are granted a

chance to repent.

“Need

money? Then give to me. Give me ten million, and I will grant you hundreds of

millions in return.” This kind of general’s song is ultimately a money chant.

Beneath it lies the money-fetish, which paradoxically reverses its nature. In

the rain of endless gold coins, the rich reform themselves. Or, as in the

film Ivan the Terrible, they drool in greed as the coins vanish endlessly

into a sack. Both possibilities coexist in the latent power of the

money-fetish.

Minseok

Chi seems to decode this ambivalent money-fetish through his character

drawings. The hidden shamanic insight in his work suggests that only after

indulging to the point of nausea in wealth, prosperity, and peace can one truly

be freed from the grip of fetishistic desire. His symbols are packed with this

notion of boundless generosity and divine blessings. Interestingly, the artist

is well-versed in Mexican mythology and peyote shamanism. The lesson in The

Teachings of Don Juan—that one must gather the sacred cactus only

after passing it by, not before—reinforces that even when peyote is needed, the

divine cactus must be approached from behind. Chi’s installation, which cuts

through the gallery air with spiritual intensity, shows the invisible

connections between Korean shamanism and Mexican myth. The cultural syncretism

across the Pacific should be noted carefully.

The

artist also remarks that only big waves in life lead to proportional growth.

This is his own story—a life of daring adventure riding unimaginable waves.

From this perspective, his post-fetishist remapping, his use of existing

cultural codes as a platform for new connotations, becomes entirely persuasive.

In

short, the dangerous yet profound proposition “transcend fetishism through

fetishism,” a notion especially prominent in cultures across the Pacific,

penetrates Minseok Chi’s artistic world. The idea of transforming cliché

tourist landscapes like the “Eight Views of Dadaepo” into a space where jealous

spirits are transcended and one enters Ocean Seal Samādhi is truly inspiring. Seeking the sublime in this way is rare,

and though post-fetishism often borrows from shamanic codes in Korean society,

whether Chi’s case will resonate in our era remains to be seen. Coca-Cola and

Cheetos may be huge in Mexico, but there’s a gap between such global trends of

the past 30 years and the internal logic of Korean art history—recall, for

instance, the Campbell’s Soup cans from within the art world itself.

Yet

it seems that only Minseok Chi is capable of fusing the worlds of the Mexican

goddess of corn, the goddess of tobacco, and the feathered cosmic serpent

Quetzalcoatl with Korean animistic traditions—such as East Coast shaman rituals

and the mythical textures of Dadaepo’s landscape. This is a wholly different

level from simply exoticizing or thematizing Aztec or Mayan motifs, or

referencing Korean diaspora figures like the Aeniken. We hope that the

divine name of the Pacific Ocean will appear again in future works, as a

symbolic bridge fusing the cultures of both shores and re-mapping shamanism

through post-fetishist practice.