Dissecting the human body was

long a taboo, even in antiquity. In his History of Animals, Aristotle

wrote: “It is not without great repugnance that one can see what constitutes

the human species.” This disgust partly explains why the ancient Greeks forbade

cadaver dissection, their aversion heightened by respect for the dead and a

distaste for blood, then considered a pollutant. Exceptions include a highly

active Alexandrian dissection school in the 3rd century BCE, made famous by

figures like Herophilos, who reportedly performed over 600 live dissections on

prisoners, sometimes in public sessions. Yet dissection was rare in the Middle

Ages, despite not being formally banned by the Church. David Le Breton, an

anthropologist specializing in representations of the body, notes that in the

Middle Ages, the body was not seen as a category of the self—as modernity would

later conceive it—but as part of the world’s symbolic system. The body was a

microcosm reflecting the macrocosm; violating its integrity was akin to

scarring the universe.

The Black Death, by necessity,

popularized public autopsies. Guy de Chauliac, one of the Middle Ages' greatest

physicians, studied plague victims, distinguishing bubonic plague from its

pulmonary form. Exposed to the dead, he contracted the disease but survived,

even performing incisions on his own buboes.

In 1532, an 18-year-old Andreas

Vesalius began secretly dissecting cadaver fragments bought from grave diggers.

Already, he suspected the ancient texts he studied at university were mistaken.

After earning his degree, he became a professor of anatomy in Padua, where he

obtained permission to dissect executed criminals’ bodies. His life's work

culminated in the monumental De humani corporis fabrica,

a 700-page anatomical treatise filled with detailed illustrations attributed to

Jan van Calcar. Vesalius died at 49, his burial site lost, as if to ensure no

one would dissect him in turn.

In 1632, Nicolaes Tulp sought to

surpass Vesalius. To cement his reputation, he commissioned a portrait of

himself teaching anatomy. The painting’s fame would eclipse his own: at 26,

Rembrandt captured a tableau of greenish flesh, taut nerves, and heavy air,

establishing himself among painters for whom the brush was a blade.

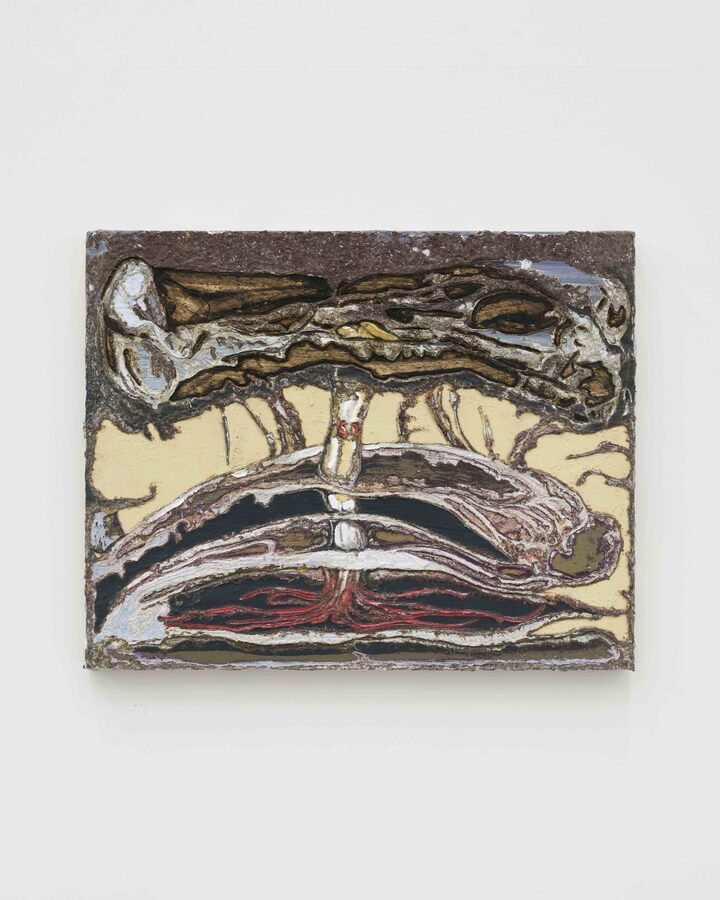

This lineage of artists—Chardin,

Ribera, Courbet, Goya, and Soutine—has long grappled with the visceral. For

Soutine, painting flayed animals released a primal childhood cry. Every wound

demands a lament. This lament arises from the unbearable collision of form and

formlessness, beauty and horror, life and death within a single image.

This dissonance echoes in

Renaissance anatomical Venuses, female mannequins with ecstatic faces and open

bellies for medical study. In Opening Venus, Georges

Didi-Huberman describes the unsettling union of Thanatos and Eros: “This

masked, disturbing hinge where being touched—moved—becomes being wounded, being

opened.” Opening a body reveals the brutal collision of worlds skin normally

separates: raw and cooked, light and dark, public and intimate.

The works here brim with this

jagged sensuality, attracting as they repel. Anna Castro de Barbosa’s blades

flirt with curves; metal and glass press against flesh in a precarious intimacy

that never resolves. The wandering glass bead replaces the wide-eyed gaze

brushed by Buñuel’s razor in Un Chien Andalou: it is

our eye, and the one that cannot look away.

Lucile Boiron’s photographs scar

the world’s origin with silent wounds, a serene clinicality tinged with stupor.

Camille Azéma’s ceramics remain feverish and strangely appetizing, their wounds

hidden in folds, tempting hands with the terrible intuition that her sculptures

might flinch under touch. Hanna Jo’s paintings, too, quiver with warmth,

inviting us into cavernous depths where organs glide and remind us of their

restless presence.

For Ondochimeg Davadoorj and

Thomas Perroteau, animation hides gestation. Every form holds others within,

poised to emerge and transform. Dissection confronts this plurality, the

eternal metamorphosis that sustains life.

For the artists of 《HARUSPEX》, the boundary is clear: it lies

where they have cut. All that remains is to tickle the still-sensitive surface

before it scars over and to embrace the liberty of existing on the edges of

comprehension, where surprise bursts forth: desire simmers in raw flesh,

passion pulses through blue veins, and faith erupts from torn hearts. In the

gash, the living overflows, and life begins anew.