Color

is by far the most conspicuous element of a painting, or any work of art liable

to be ‘hanged on a wall’.

However Changkon Lim’s paintings have none of that. By ‘none’ I do not mean the nonexistence of

color, but the singleness of color used by the artist. Did Lim choose his works

to be unicolor because he finds color important, or is it for the opposite

reason? Facing this blatant question the artist made a roundabout statement

that it is subject to further thought, yet I could not help but linger on it.

Changkon Lim’s golden paintings reminded me of the

former court painter Francisco Goya’s latter years

works, the Black Paintings (Pinturas Negras) [1].

How did it come about that, for the artist is such a young

painter? Goya worked on his Black Paintings supposedly

throughout the same gloomy years he lost his hearing; yet they prevailed over

the royal family’s portraits

during his era as a court painter, when it came to capturing the essence of

human nature with an almost expressionistic stroke and subtlety. Presumably,

Goya’s latter years paintings’

characteristics overlapped with Changkon Lim’s strokes

and his quest for human existence. This review thus aims to thoroughly look

after Changkon Lim’s works and satisfy one’s curiosity upon them, especially by focusing on forms,

compositions, and methodology adopted in the artist’s

solo show ‘48! Morphing Gesture’.

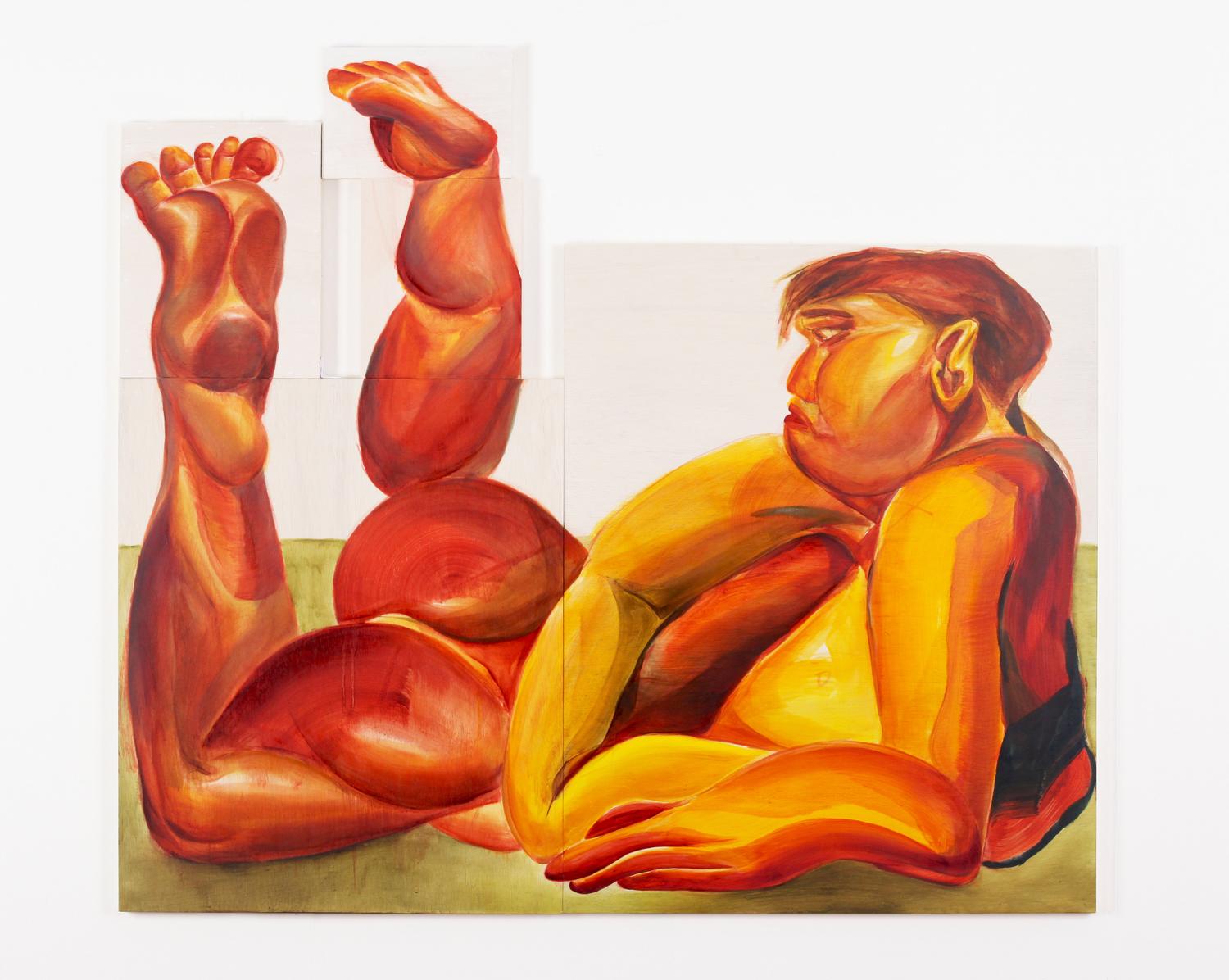

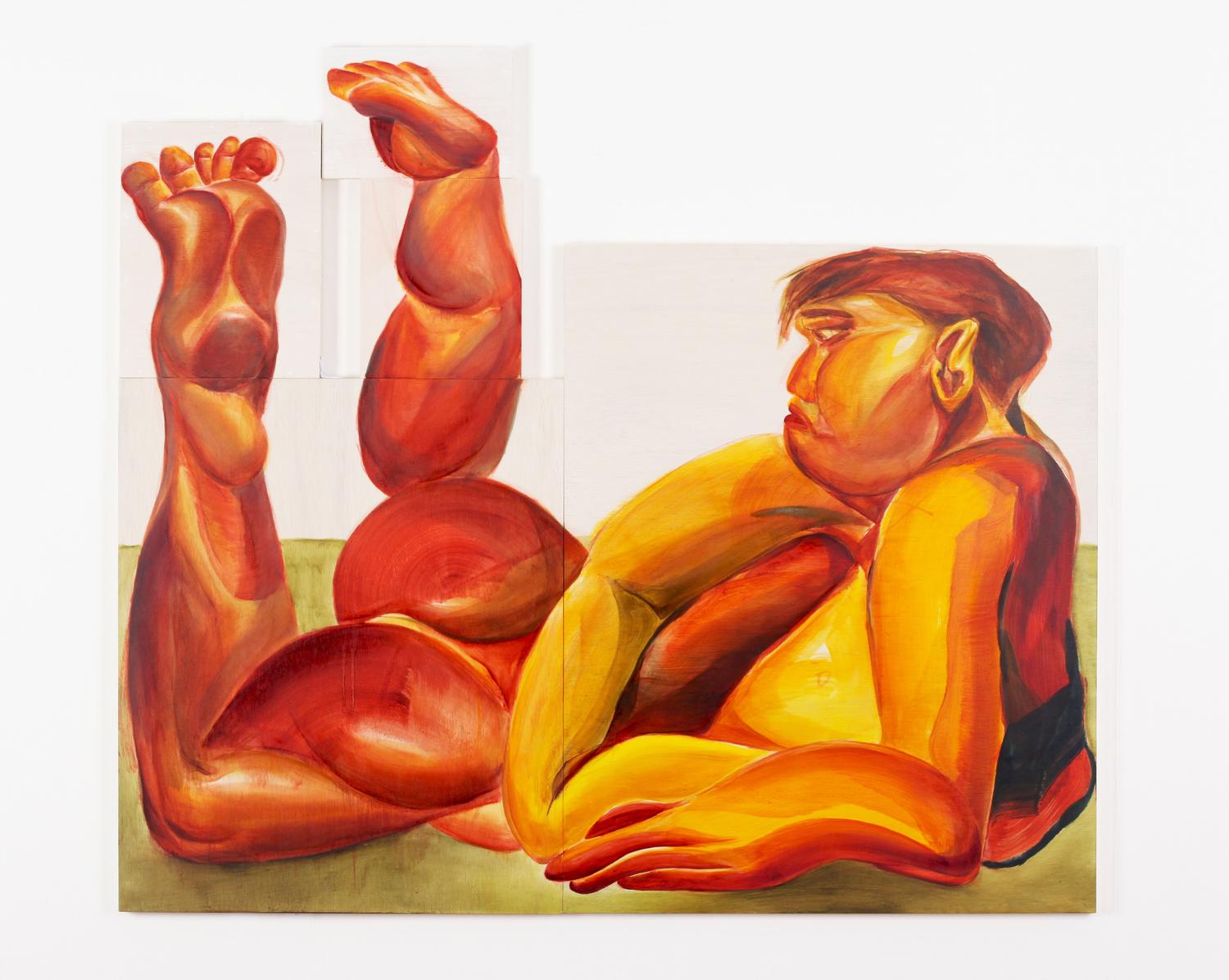

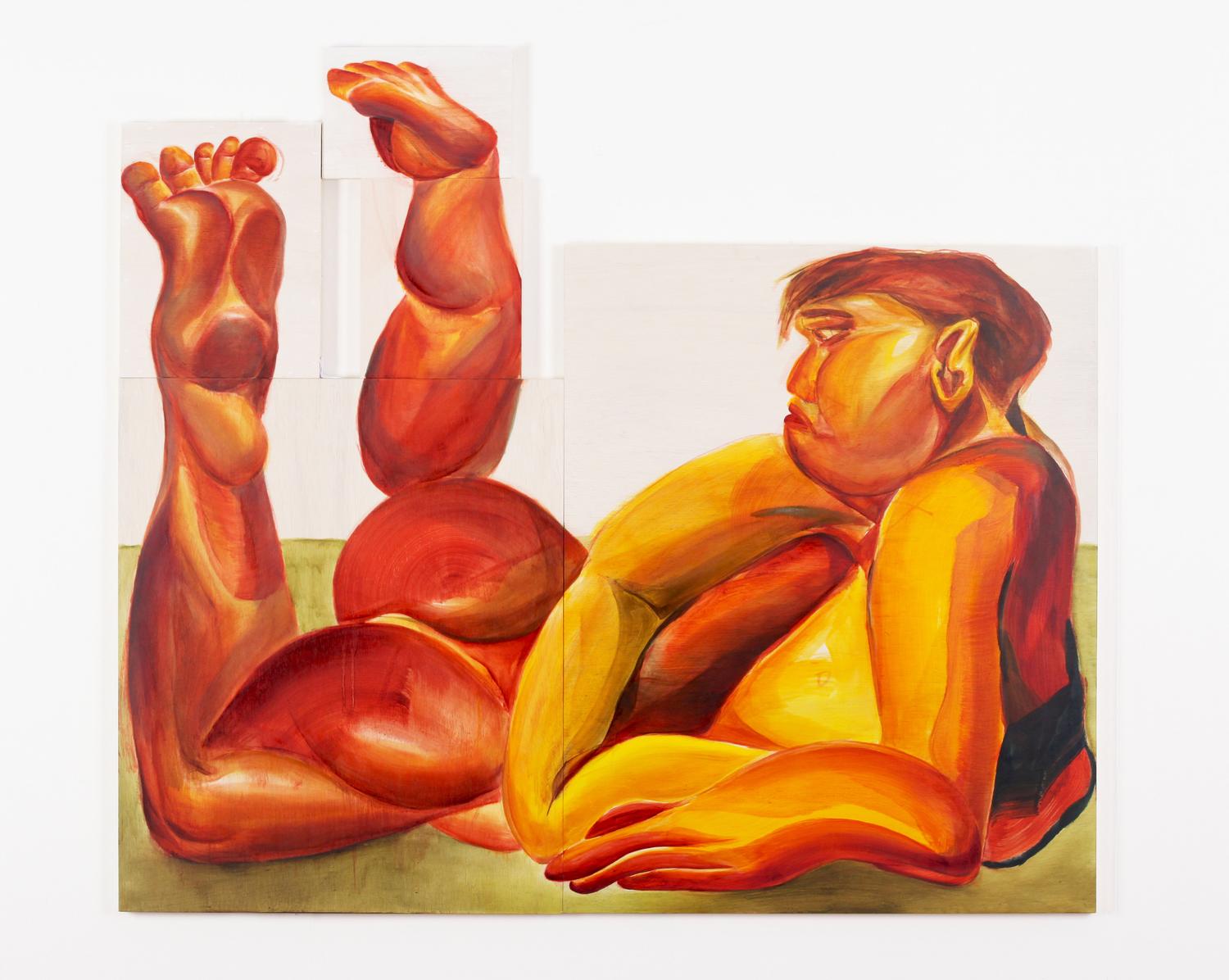

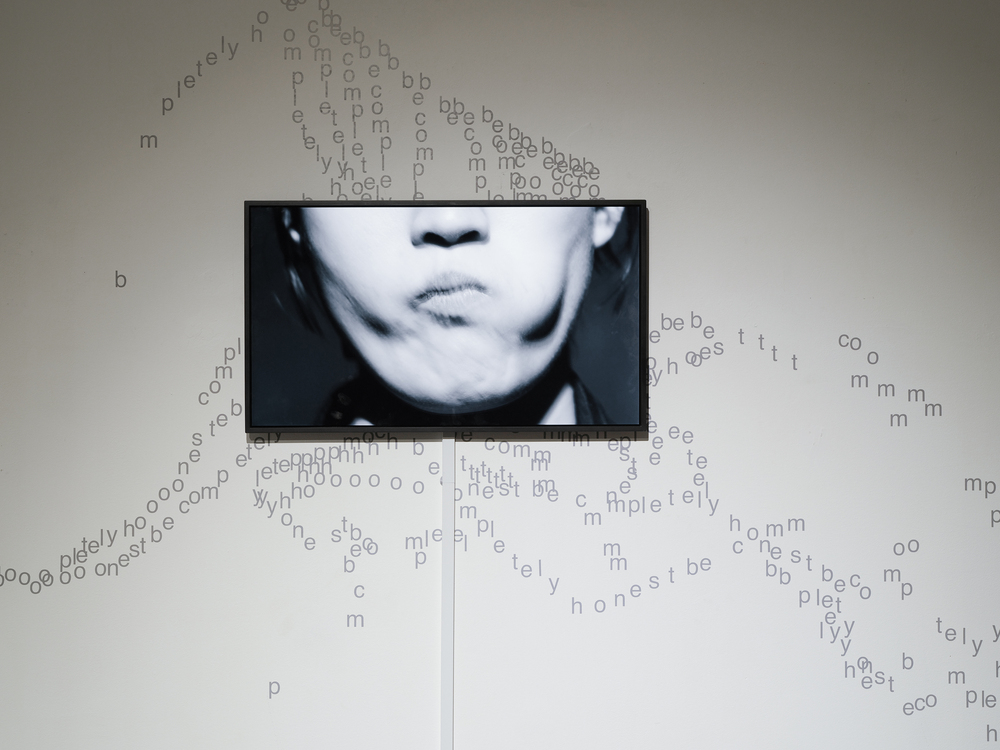

A ‘body’ at last; a body

can be found by associating the curves of muscles, prominent and secretive at

the same time, yet we end up recognizing its twisted hands and feet. Changkon

Lim works on the body and the identity, and in his works the artist’s body forms several counts: a body that paints and slices (a

movement on the panel), and another body that assembles (a movement in space),

and these bodies interlock to reveal the form of a Body (as an artwork).

Lim currently uses wooden panels as the main support and body of his

works. The panel is an honest material; it instantly reveals all reactions

caused by the artist’s action. Hiding them during the

painting-slicing-breaking process is of course impossible. When applying

physical force becomes an analogue to the irreversible state, it also indicates

putting oneself to the solving of a problem at hand. The artist expressed this

process as ‘a talk with the material’: indeed his movements and the panel’s

responses - sometimes split accordingly, sometimes caved in unexpectedly - are

similar to the process of ‘experiencing’ the material as a talk falling short or picking up. The body

reveals itself in full completion, through the artist’s

own body handling the panel and afterwards by overlapping with his subtle brush

strokes.

Changkon Lim mentioned once in A Vacant Man (2018~2019)

series that he “felt his body plunging into the white

wall featuring the hanged panel”. However in his recent

work Morphing Gesture (2022), he instead “felt his body being thrown out of the panel” [2]. The statement underlines the most noticeable difference in his

new work, as the artist attempts to change several mechanisms of his work for

this exhibition. Firstly, the main work of the exhibition, Morphing

Gesture, implies the pliability of form: during the three weeks of

the show, Lim will constantly change the arrangement of Morphing Gesture[3]. In the same context as the “experience” of handling the material, the

artist still finds great importance in the relation between his work and

himself. “As if fighting with his own body”, Lim struggles to find the ideal form, which he reveals and mixes:

that is the reason why he focuses on the body at the very moment[4]. Each single sculptural piece has taken up more space than his

previous works have, surpassing the human scale to cover the whole wall up. In

this way, his (polysemous) body(ies) aims the possibility of extensibility. The

feeling of aforementioned “body being

thrown out to the space” is most likely caused by the

shifting sense, with the extension of the artwork’s

component to a real (equipped with a wall, ground, and ceiling) ‘space’ and the ‘movement’ filling it, instead of remaining in the two-dimensional ‘surface’ like before.

Meanwhile, the Crystals series are formed

from leftover pieces of wood panels, after cutting the forms; they too are

ought to be singular artworks depending on the composition. Crystals,

glow, Crystals, landscape and other (temporarily)

so-called Crystals to be presented in the exhibition hold the

potential of becoming a new being, just as snowflakes become a snowball and

snowballs (temporarily) materialize as a snowman by clumping together. This would

be Changkon Lim’s way of imagining what a put-together

sculpture could perform and making it exist, thus “placing

it before one’s very own eyes and experiencing it”[5].

Whereas Morphing Gesture and Crystals series

are about the form of the body, in other words related to shapes, other works (a

pool of water (2022) and a path of air (2022))

are closer to a painting, using only brushstrokes and refraining from “revealing the form through cuts and chiseling”. This way they show us ‘the inside’ of the body hidden until now. While feeling like spin-offs they

make us imagine about existence once more, since we cannot exactly state their

shapes. Perhaps they could be regarded as (imaginary) landscapes, circulating

inside a place called the body, revealing themselves all of a sudden before

disappearing.

Morphing Gesture is ought to be mixed and

re-assembled together on a daily basis, revealing itself to be part of Crystals previously.

One day it creates a path of air and forms a pool of water. In

the end Changkon Lim’s works are his persona, a way of

verifying the alikeness and difference between you and I, out of the same

pocket[6]. The subject (the artist’s movement) and the object (the images in his works) move and

correspond altogether, only to surpass the limits of the medium. Lim explores

the existence, body and movement through relation. Put in a more radical

thought, perhaps what he had wanted to talk about, would it not be love?

Therefore Changkon Lim explores the most radical issue by using the most

traditional method (which could be expressed as the carving of images, an act

in between painting and sculpture). Then let us call his works, ‘Golden Paintings, Bodily Shouting out Love’.

[1] The body of works featuring 14 paintings Francisco Goya had

painted, presumably between 1819 and 1823.

[2]Features in the e-mail exchanged between the artist and the

curator.

[3]The viewers would then experience each time a newly-assembled

version of the work, and the previous combinations are to be archived online.

[4] Since his first solo show, the ‘Bulging Scenery’ in 2019, Changkon Lim has

been constantly shifting between canvases and panels, between the act of

painting and sculpting, in order to depict the body and identity.

[5] During our meeting Changkon Lim has once talked about the

difficulty of imagining. Rather than coming from infeasibleness, this

difficulty resides in the lack of testimony. For an artist as empirical and

existential as Lim, the visibility becomes a crucial motivation whereas

imagination remains in the invisible area, and is related to recalling

something that is then hidden to our eyes (and inexperienced by extension).

Nevertheless Changkon Lim constantly talks about the act of imagining in his artist’s statement (“(…)

imagining the combining and ever-changing times of the future. Imagining what

is unseen to my very own eyes. Imagining the inside of my own body. Imagining a

space that can both be a body and a landscape.”),

probably because in this solo show ’48! Morphing

Gesture’ he tries himself to craft the process of

imagination morphing into experience.

[6] The pocket is a metaphor encompassing material, work,

identity, and so much more.