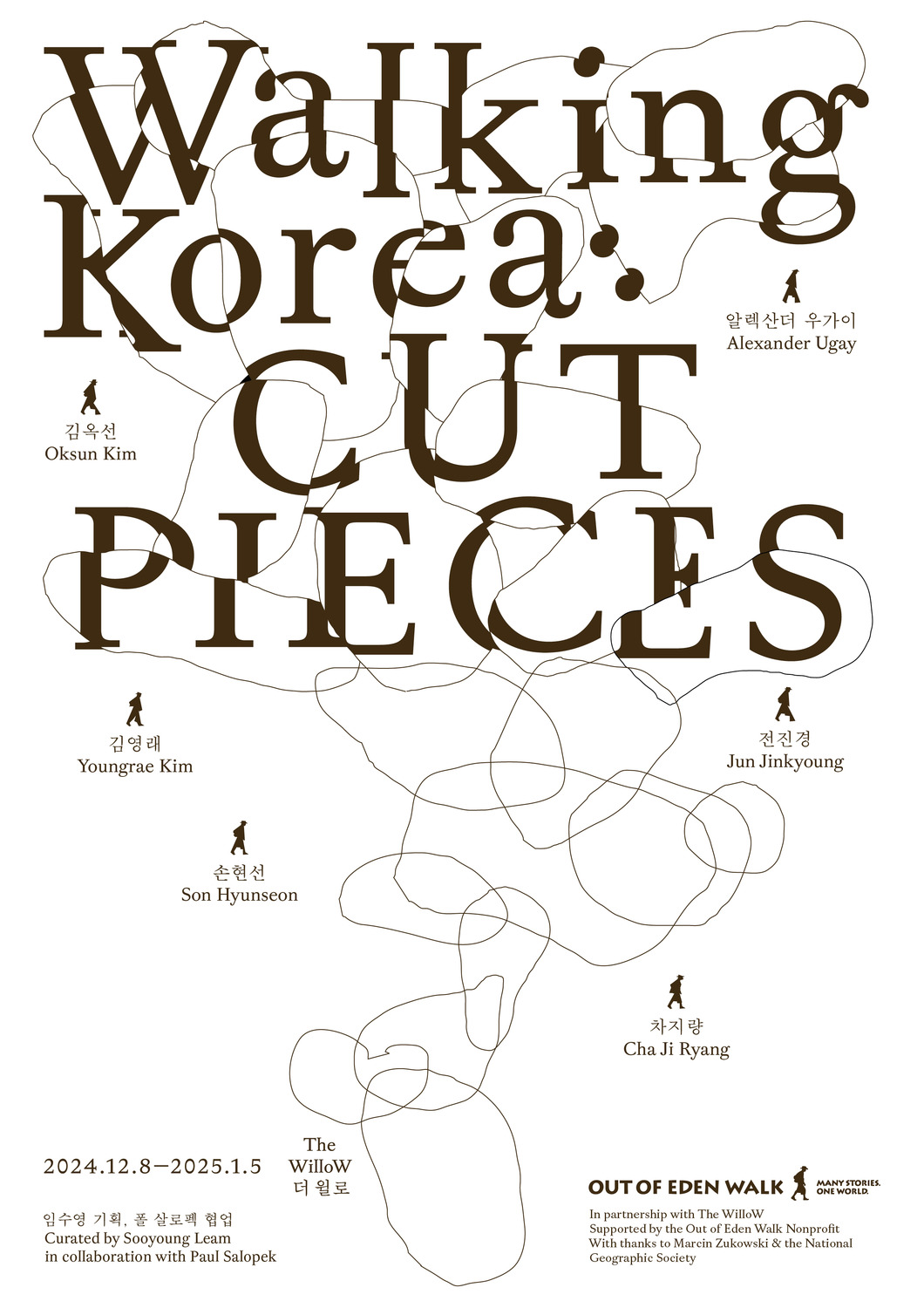

I

first encountered Son Hyunseon’s paintings during the last winter of 2015. At

the time, I happened to visit Seongbuk Art Creation Center, where the

exhibition 《Future Style 展》, organized in collaboration with the Korea National University of

Arts, was underway. The imagined future presented by the exhibition was based

on Hiroki Azuma's “Database Consumption Theory.” Inside the exhibition space, I

received the works like two-dimensional prophecies or three-dimensional

monuments. Each of them maintained their respective volumes as a kind of

greeting to an era yet to arrive.

Even

back then, Son Hyunseon was exhibiting ceiling fans. Several paintings depicted

ceiling fans either spinning or stationary, installed in different

architectural interiors. The title Shape of Motion,

printed discreetly in small font on the caption, caught my eye immediately. It

conveyed a sense of honesty and decisiveness. In the same space, the works of

Kim Jungtae and Neonim Express were installed—both had manually transformed the

digital resolutions of floating jpg and gif images found online, intuitively

recalling the exhibition’s theme. Even if art of the future amounts to no more

than temporarily promised, fictional imagery, the fact that these works

identified arbitrary coordinates and documented them meant that each could

still serve as a visual mapping resource.

Yet,

Son Hyunseon’s paintings seemed to stand apart, isolated from the vividly or

roughly rendered works around them. The rows of ceiling fan paintings,

installed with unwavering distance and order, differed fundamentally from Kim

Jungtae’s method of layering various frames atop each other or assembling them

into compound values, and also diverged from Neonim Express’s obsessive

translation of politically charged sentiments into images. What I felt when I

first confronted Son Hyunseon’s paintings was not delight or astonishment but

perplexity. The paintings demanded an independent mode of viewing, as much as

they dealt with their own painterly themes.

For

instance, one could admire the pictorial techniques composed with the grammar

of graphic editing software, feel déjà vu from digital landscapes reimagined

with physical materials, question the boundaries of painting by gauging the

paper through fragmented shapes and symbols, or take several steps away from

attempts to reassemble Seoul with construction materials and abandoned

buildings. But while standing in front of the paintings, no particular

awareness or knowledge was required. All the viewer needed to do was

endure—that was all.

The

same was true when I visited the current exhibition: all I had to do was endure

for a long time. Over two years, the subject had shifted from ceiling fans to

concrete mixer trucks. After briefly reading the exhibition leaflet placed next

to the guest book—and hesitating whether to sign my name—I eventually wrote it

down. The phrase “the idea of everything that rotates,” mentioned in the

introduction, lingered in my mind. Was it because this expression neatly

dismissed Son Hyunseon’s paintings? Or was it because the phrase precisely

struck the core of Son’s paintings?

When

I first saw the ceiling fan series, I had to invent countless explanations on

the spot, as that felt necessary to understand and process Son Hyunseon’s

paintings. Paintings that demand explanation. Most exhibition statements are

intended as verbal guides to help audiences comprehend the work, but for some

reason, the more I read statements about Son’s paintings, the more elusive they

became. (The statement for 《Future Style 展》 in 2015 described the work as “an attempt to visualize the

sensibility of ‘future style’ by presenting surfaces where depth has vanished,

through depicting objects of repetitive motion, eliminating the central axis

and leaving only movement.”) One of the few explanations I managed to formulate

back then resembled the statement from this exhibition: perhaps this artist is

interested in the essential rhythm of objects. Perhaps that’s why they painted

not stationary but rotating ceiling fans. In fact, Son’s paintings of rotating

objects directly depict pictorial elements proportional to speed—such as

trajectories and blurs. Yet all three explanations sounded more like commentary

on Son Hyunseon than on the paintings themselves.

Therefore,

this time I tried to conjure explanations solely about Son Hyunseon’s

paintings, without the artist. Standing alone in front of the paintings for as

long as I could—this was the first time I managed that. Inside the gallery,

emptied of visitors, the space appeared defined only by light and shadow. A

middle-aged man with subtly different expressions stood at intervals like the

paintings, as did ceiling fans, some still and some rotating, as did the

concrete truck series—at a glance resembling moon craters or smooth-surfaced

bas-reliefs—and the ceiling fan series installed inside the glass windows,

visible only from outside the building. I tried to endure them all. Especially

the outdoor works, located near the road, constantly exposed me to danger,

which somehow heightened my sense of endurance. Every time I was pushed away

and returned to my spot, I could grasp the sensation of the waves.

In

the process of enduring before the paintings, accumulating time, forgetting and

remembering repeatedly, I was the wave, the wind, the atmosphere, and

simultaneously, the feeling itself. Plausible explanations pressuring quick

understanding were gradually denied, one by one, in a calm sequence.

Eventually, only the paintings and I remained.

Suddenly,

a thought stirred my vacant mind. I opened my messenger and sent myself this

sentence:

“There comes a moment when I get confused—whether the essential rhythm of this

object is a tremor, or whether my heart is trembling, making it appear so.”

If

I were a sphere, everything would appear to be rotating while I’m spinning. Not

only objects, but even the horizon itself. Just like how, for someone in

constant free fall, everything seems to collapse moment by moment. So, what can

we do? When I ask again the same question I once heard, I am spinning endlessly

in a horizontal or vertical direction. Because of the rotation speed, my words

cannot be delivered intact. The person listening to the question must infer the

missing segments on their own.

We e-n-d-u-r-e.

Someone answers, their face tilted to one side. Even while vomiting from

nausea, they nod their head.

We e-n-d-u-r-e.

When I return those words, I feel deeply melancholic. Is it because I can no

longer return them?

As

I left the building and headed toward Hongdae Entrance, I typed “Standstill”

into the YouTube search engine. Instead of “Standstill,” the results leaned

more toward “Stand still.” It seemed that in English-speaking cultures, this

term was mostly used as a song title. As I scrolled down, I found and clicked

on the video, “Stand Still [Live]” by The Isaacs.

While listening to the song, I heard these lyrics:

Stand

still and let God move,

Standing still is hard to do

When you feel you have reached the end,

He’ll make a way for you

Stand still and let God move

On

the way home, I encountered countless spheres precariously leaning on upright

skeletal structures. They were endlessly spinning, which made them appear

almost expressionless. Perhaps expressionlessness is closer to a state of

rotation rather than a state of stillness. Objects moving beyond a certain

frame rate can even appear completely still. Like how we mistakenly think we

“see” high-speed spinning tires.

It’s

extremely rare for me to go see an exhibition alone. Recently, I haven’t even

gone out at all. But someone’s advice about “faith” gave me the courage to step

out for the first time in a long while. I’m not sure if it’s alright to quote

them, but that person said they believe in the painting itself, rather than

their own sensibility, talent, or aptitude. Even though they create the work,

the painting always exists ahead of them, or behind them. Whenever they feel

afraid, they remind themselves: even if I cannot believe in myself, I can

believe in the work.

I,

on the other hand, have never thought to separate my writing from myself, just

because I wrote it. So maybe I’ve been under the illusion that what determines

my writing is simply my own sensibility, talent, or aptitude. But as they said,

sometimes a work decides itself. Some of the writings my colleagues liked were

not good because I wrote them well—the writing itself was good. Thinking that

way means there’s no need to be humble or arrogant. All that’s needed is a body

that can honestly endure.

These

days, when I close my eyes, I no longer hear Basinski or Bizet’s music.

Instead, K’s voice, repeating calibration phrases into a closed-circuit video

device, overlaps like polyphonic music, echoing here and there:

interlinked.

I

need to treat my writing and myself as independent units.

within cells.

While

enduring, I should not wait for a benevolent god or an experienced guide, but

instead focus more deeply and closely on the landscape of collapse, the

Generation-scape, and the sensation of falling that defines my generation.

My

fellow companions, who are falling with me, ask:

So, what can we do?

Spinning, I answer:

We e-n-d-u-r-e.

Everyone

is enduring, without compensation. Falling. Without tension. As if it’s only

natural. Or imagining, underfoot, a ground that disappeared long ago. Now

saying, foolishly: everything is collapsing.

The

intercity bus No. 1008, departing every 30 minutes from Sadang, traces the

straight roads connecting my home to Sadang. There are no detours. It stops

just once at the Uiwang Expressway tollgate. If you board during off-peak

hours, you have to press the bell within 20 minutes. On the bus, all I do is

listen to music and look out the window. During the day, I see the scenery

outside. But at night, I see my own face.

On the bus ride home, I can’t help but glance at my face reflected at an angle.

In the midst of everything spinning, I am the sphere striving to endure the

nausea, standing still.

1.

Image Source: http://chapterii.org/chapter-ii-window-4/

2.

Hito Steyerl, Expulsion from the Screen, translated by

Kim Silbi, Workroom Press, 2016

3.

Image Source: https://neolook.com/archives/20151213h

4.

The Isaacs – Stand Still [Live] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QlBFlEup9Uc